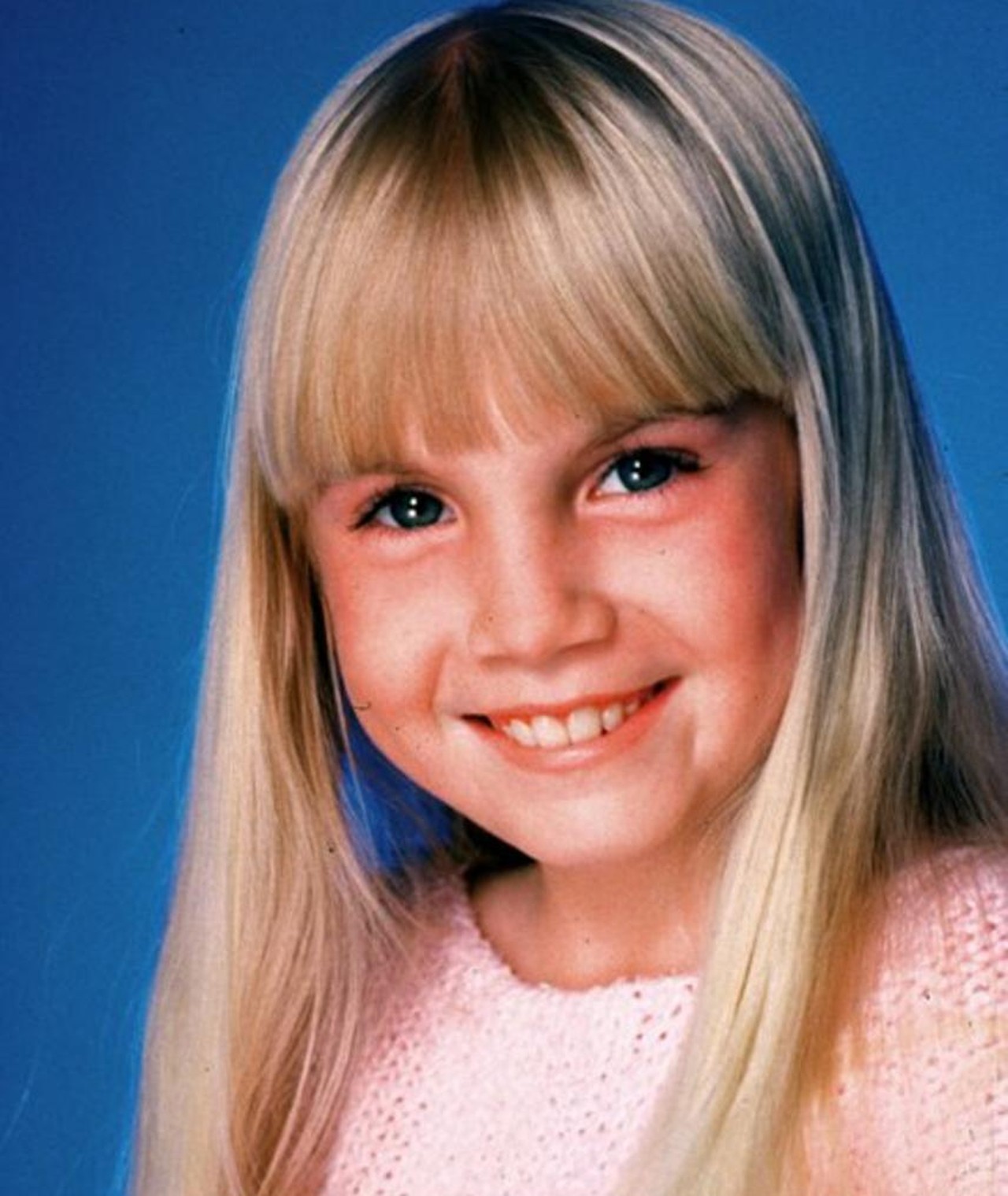

If you grew up in the eighties, you know the face. That shock of white-blonde hair, those wide blue eyes, and the chillingly calm voice saying, "They’re he-ere." Heather O'Rourke wasn't just a child actor; she was the emotional anchor of the Poltergeist trilogy. But her legacy is often buried under layers of Hollywood ghost stories and "curse" theories that, frankly, do a disservice to the actual tragedy.

What happened to Heather O'Rourke wasn't supernatural. It was a medical failure.

She was only twelve years old when she died. One day she was eating breakfast, and the next, she was gone. The shockwaves of her passing in 1988 didn't just haunt her family; they fueled a decades-long obsession with the idea that the Poltergeist films were hexed. People love a good campfire story, but the clinical reality of Heather’s final months is way more haunting than any movie script.

The Long Road of Misdiagnosis

It basically all started in early 1987. Heather began feeling sick while living at her family's home in Big Bear Lake. Doctors initially thought she had contracted giardiasis—a parasitic infection—from the local well water. It made sense at the time. She was treated for it, but the symptoms didn't really clear up the way they should have.

Then came the second guess.

Doctors at Kaiser Foundation Hospital diagnosed her with Crohn’s disease. This is where things got complicated. They put her on cortisone injections to manage the inflammation. If you’ve ever seen photos of Heather during the filming of Poltergeist III, you might notice her cheeks look a bit "puffy." That wasn't just puberty; it was a side effect of the steroids. Her mother, Kathleen, later mentioned how self-conscious Heather felt about her changing appearance. Imagine being twelve, starring in a major motion picture, and dealing with a moon-face reaction from meds you might not even have needed.

The real problem? She didn't have Crohn's disease.

💡 You might also like: Pamela Anderson Net Worth: Why the Numbers Don't Tell the Whole Story

The Final Forty-Eight Hours

By the time January 1988 rolled around, Heather seemed to be doing better. She was back in school, being a regular kid. But on January 31, she woke up feeling like she had the flu. Nausea. Chills. The usual stuff that parents usually treat with Gatorade and bed rest.

The next morning, February 1, things turned critical fast.

She collapsed at the breakfast table. Her fingers were blue. Her feet were cold. Her parents called the paramedics, and things moved at a terrifying speed from there. During the ambulance ride to a local hospital in El Cajon, Heather suffered her first cardiac arrest. Paramedics managed to restart her heart, but she was in bad shape. She was airlifted to Children’s Hospital in San Diego, where doctors finally realized the "Crohn's" diagnosis was a catastrophic error.

She didn't have a chronic inflammatory disease. She had congenital stenosis of the intestine.

Basically, she had been born with a narrowing of the bowel. Over time, that narrowing caused a massive obstruction. Because it hadn't been caught, the bowel eventually ruptured, leading to septic shock. This is a massive, body-wide infection that shuts down organs. Heather went into emergency surgery to clear the blockage, but her body was already too weak. She suffered a second cardiac arrest on the operating table and was pronounced dead at 2:43 p.m.

Why the "Curse" Took Over the Narrative

You’ve probably heard about the Poltergeist curse. It’s the kind of lore that tabloids live for. People point to the death of Dominique Dunne (who played the older sister in the first film), who was tragically murdered by an ex-boyfriend. Then there was Julian Beck and Will Sampson, who both died of natural causes after the second film.

Heather’s death was the tipping point. Because she was so young and it was so sudden, the public looked for a "why" that made sense in a dark, cinematic way. The story that they used real human skeletons on the set of the first movie only added fuel to the fire.

But honestly? If you talk to medical experts, they’ll tell you that Heather’s condition, while rare to be asymptomatic for so long, was a physical reality, not a spiritual one. Dr. Daniel Hollander, a gastroenterology expert, once noted that it was "distinctly unusual" for such a defect to not show symptoms earlier in life. That rarity is what led to the misdiagnosis, and the misdiagnosis is what led to the tragedy.

The Legal Battle and the Aftermath

Kathleen O’Rourke eventually filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Kaiser Foundation Hospital. The claim was pretty straightforward: if the doctors had performed the right X-rays or interpreted them correctly earlier, they would have seen the blockage. It could have been fixed with a routine surgery months, or even years, before it became a life-threatening emergency.

The case was eventually settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. But no amount of money fixes the hole left by a kid who was just starting to find her voice as an actress.

Poltergeist III was released four months after she died. The director, Gary Sherman, didn't even want to finish it. He was devastated. They ended up using a body double for the final scenes, which is why you never really see "Carol Anne’s" face in the ending of that movie. It’s a hollow, eerie experience to watch it knowing the lead actress wasn't even there to see the wrap.

👉 See also: Celebrities Born August 30: The Powerhouse List You Probably Didn't Realize Shared a Birthday

What We Can Learn From Heather’s Story

Heather O'Rourke's story is a reminder that even in the world of Hollywood glitz, the most dangerous things are often the ones we can't see. It wasn't a ghost in a TV. It was a silent physical ailment that went ignored.

If you’re looking for the "actionable" part of this story, it’s about medical advocacy. Misdiagnosis happens more often than we’d like to admit, especially with gastrointestinal issues in children.

- Trust your gut (literally): If symptoms like chronic bloating, nausea, or localized pain don't go away with standard treatment, push for a second opinion or more intensive imaging (like a CT scan or specific X-rays).

- Question the "flu": Sudden, violent illness that involves cold extremities or blue tinting in the skin is never just a flu. It’s an emergency.

- Research "Rare" conditions: Congenital issues don't always show up in infancy. Sometimes the body compensates until it just can't anymore.

Heather is buried at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, just a few feet away from her onscreen sister, Dominique Dunne. They are both gone way too soon, leaving behind a legacy that is much more than just a "cursed" film franchise. They were real people with real families, caught in circumstances that were far more tragic than any horror movie could ever depict.

If you want to honor Heather, watch her work. Look at the talent of a kid who could hold her own against veterans like Craig T. Nelson and JoBeth Williams. She wasn't a victim of a curse; she was a brilliant light extinguished by a medical system that looked, but didn't quite see.

The best way to remember her is to separate the girl from the ghost stories. She deserves that much.

Next Steps for Further Reading:

For those interested in the medical specifics of Heather’s condition, you can look into the clinical studies regarding acute intestinal stenosis and the ways it mimics Crohn's disease. Understanding the nuances of pediatric GI health is often the first step in preventing similar tragedies in the future.