August 18, 1920. Tennessee finally ratified the 19th Amendment. That was the "perfect 36th" state needed to make the right to vote a constitutional reality. For white women, it was the end of a seventy-year slog. But if you’re asking could black women vote in 1920, the answer isn't a simple "yes" or "no." It’s more of a "technically yes, but actually, it depends on where you lived."

Basically, the law changed. The reality didn't.

For millions of Black women, especially in the South, 1920 wasn't a finish line. It was just another day in a long, grueling fight against Jim Crow laws that didn't care what the Constitution said. While their white counterparts were heading to the polls to celebrate, many Black women were being met with literacy tests, poll taxes, and literal physical threats. It’s a messy part of American history that usually gets glossed over in standard textbooks.

The Legal Reality vs. The Southern Reality

On paper, the 19th Amendment was colorblind. It stated that the right of citizens to vote "shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." That's it. No fine print about race.

But here’s the kicker: the 15th Amendment had already "guaranteed" the right to vote regardless of race back in 1870. We all know how that turned out. By 1920, Southern states had spent decades perfecting ways to keep Black men away from the ballot box. When Black women tried to claim their new rights, those same dirty tricks were waiting for them.

Take Mary Church Terrell, for instance. She was a powerhouse. She was one of the first African American women to earn a college degree and a founding member of the NAACP. She fought like hell for suffrage. But she knew that for her sisters in the South, the 19th Amendment was a hollow victory without federal enforcement. She famously said that Black women were carrying a "double burden" of being both Black and female.

✨ Don't miss: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

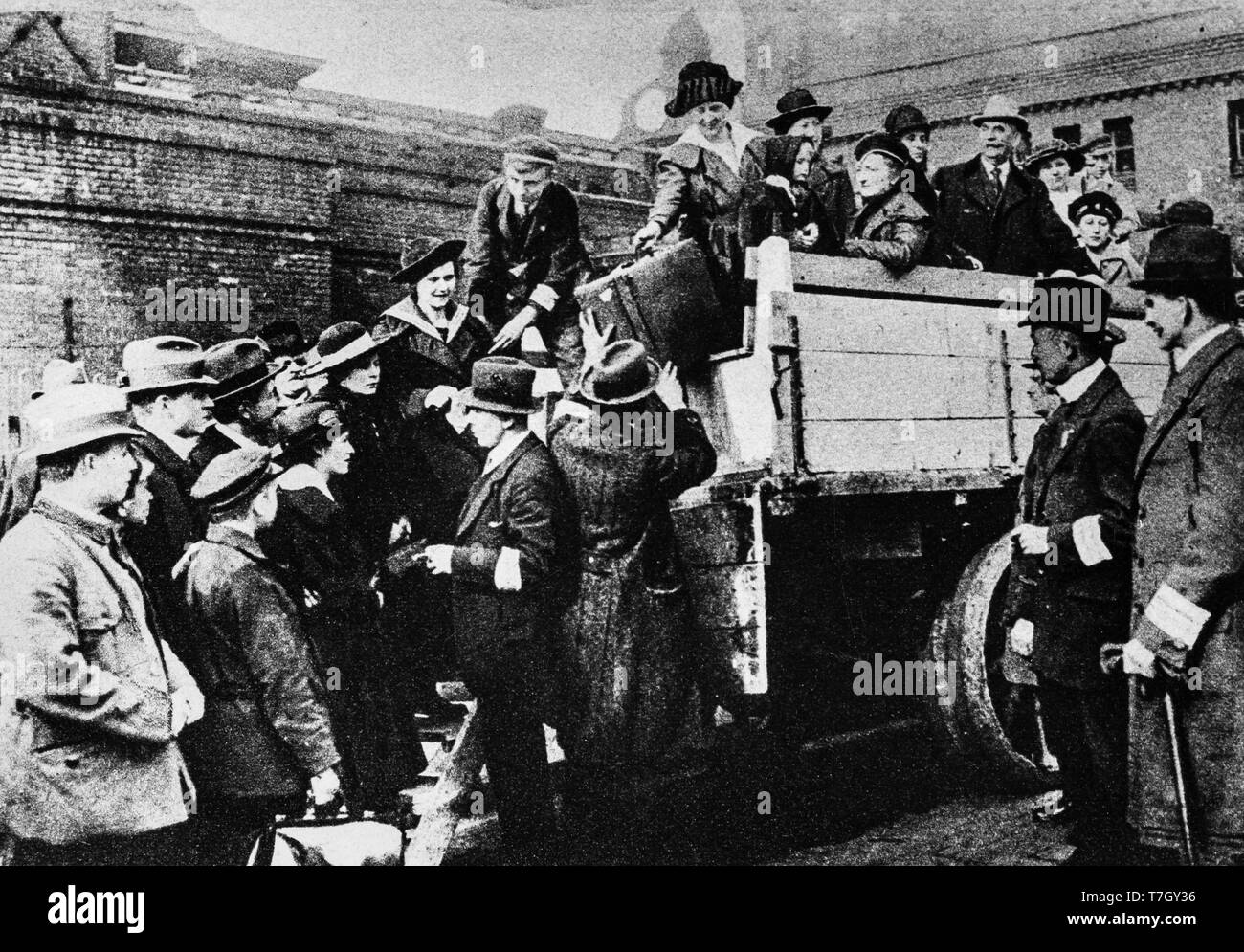

In places like Florida and North Carolina, Black women actually did show up in huge numbers in 1920. They organized "suffrage schools" to teach each other how to pass those bogus literacy tests. In Daytona, Mary McLeod Bethune led a massive voter registration drive. The KKK actually marched through her school grounds the night before the election to try and scare them off. She didn't budge. She and her students stood their ground, and the next day, they marched to the polls.

Why 1920 Didn't Mean What We Think It Meant

We like clean narratives. We like to think a law passes and then—poof—everything changes. It doesn't work that way.

The 19th Amendment didn't actually give anyone the right to vote. It just prevented states from using gender as a reason to deny it. This is a crucial distinction. States were still allowed to deny voters for other reasons, like "failing" to interpret a complex section of the state constitution to the satisfaction of a white registrar.

Imagine being a Black woman in 1920 Birmingham. You walk up to the registrar. He asks you to recite the entire Declaration of Independence from memory. Or he asks you how many bubbles are in a bar of soap. That’s not an exaggeration; those were actual tactics used to disenfranchise people. If you couldn't "pass," you didn't vote. Period.

The Northern Exception

Now, if you lived in Chicago or New York in 1920, the story was different. In the North and West, Black women were often able to vote with much less interference. They became a significant political force almost immediately.

🔗 Read more: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

In Chicago, the Alpha Suffrage Club—founded by the legendary Ida B. Wells-Barnett—was instrumental in electing Oscar De Priest, the first Black alderman in the city. Wells-Barnett understood power. She knew that the vote was a tool for protection. She had seen too many lynchings and too much violence to think that anything less than political agency would keep her people safe.

The Suffrage Movement's Internal Betrayal

It’s painful to talk about, but many white suffragists weren't exactly allies.

Leaders like Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul were often willing to throw Black women under the bus to win over Southern white legislators. During the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession in D.C., Black women were told they had to march at the back of the parade. Ida B. Wells-Barnett basically said "absolutely not" and slipped into the Illinois delegation mid-march anyway.

This tension is why the question of could black women vote in 1920 is so loaded. Even within the movement meant to empower them, they were often treated as an after-thought or a liability. The 19th Amendment was a victory, but it was a partial one that left millions behind.

The Long Game: From 1920 to 1965

If you think the story ends in 1920, you're missing the most important part. Because the 19th Amendment failed to protect Black voters, the struggle just shifted gears. It took another forty-five years of protests, beatings, and murders to get the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

💡 You might also like: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

That 1965 legislation was the real "19th Amendment" for most Black women in the South. It finally put some teeth into federal law, allowing the government to step in and stop the discriminatory practices that had been standard operating procedure since the late 1800s.

Fannie Lou Hamer is the name you need to know here. In 1962, she tried to register to vote in Mississippi. She was fired from her job, kicked off her plantation, and later brutally beaten in a jail cell. She didn't stop. Her testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention turned the stomach of the nation and helped pave the way for real reform.

Actionable Insights for Today

Understanding the nuance of 1920 isn't just a history lesson; it's a blueprint for recognizing how systemic barriers work. Laws are just words on paper if they aren't enforced.

If you want to honor the legacy of the women who fought for the vote in 1920—and those who were denied it—there are specific ways to engage with that history today:

- Support Voter Protection Organizations: Groups like the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) or Fair Fight Action continue the work that started after 1920 by fighting modern-day voter suppression.

- Research Local History: Most people don't know the names of the Black suffragists in their own towns. Dig into local archives or historical society records to find the "Mary McLeod Bethunes" of your community.

- Acknowledge Intersectional History: When celebrating milestones like the 19th Amendment, always include the context of race. True history is never just one-dimensional.

- Check Your Registration Status: Given the complexity of voting laws today, ensure you are registered and understand the ID requirements in your specific state.

The year 1920 was a milestone, certainly. But for Black women, it was less of a door opening and more of a crack in a very thick wall. It took decades of hammers and chisels to finally break through.

Source References and Further Reading:

- Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Martha S. Jones.

- Lifting as We Climb: Black Women's Battle for the Ballot Box by Evette Dionne.

- The National Archives: Records of the Women's Bureau.

- The Library of Congress: "Black Women’s Suffrage" digital collection.