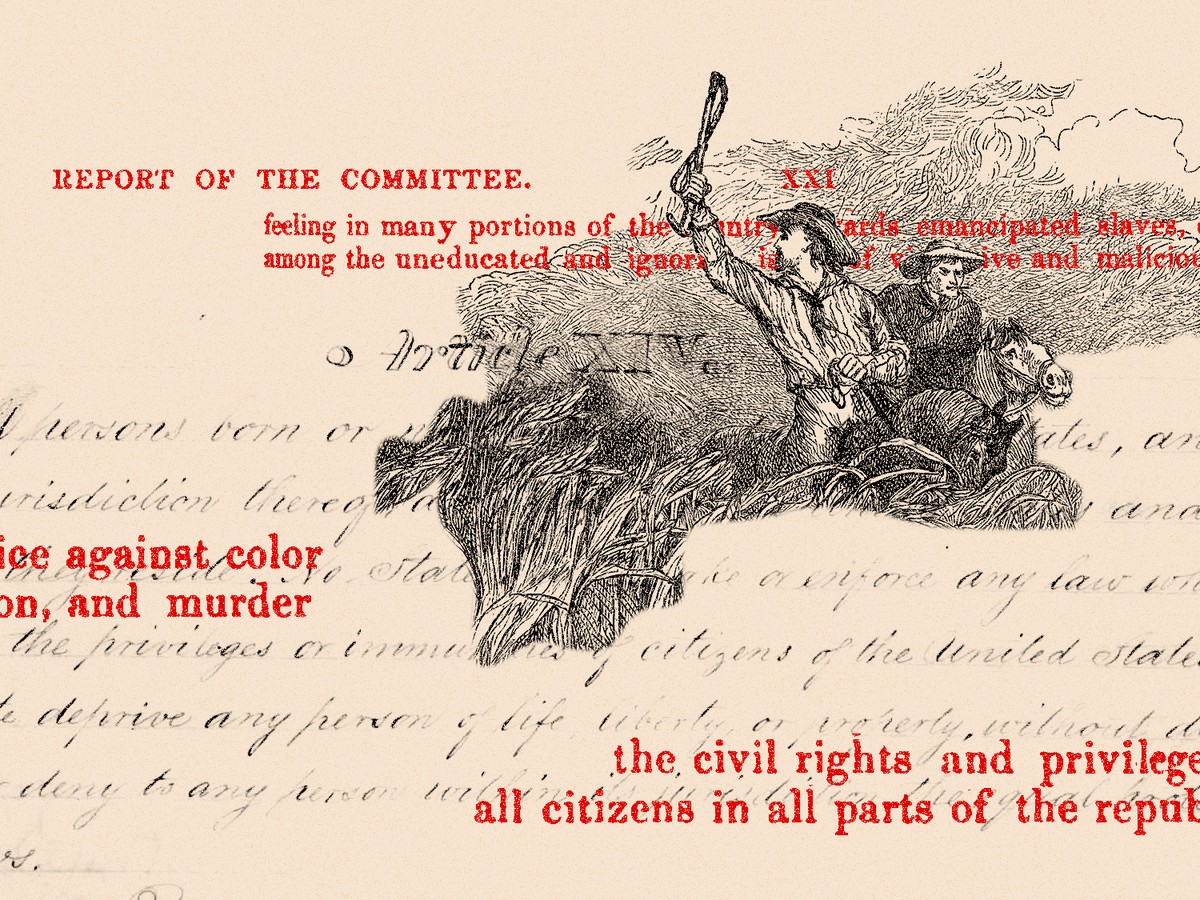

You’ve probably heard the 14th Amendment called the "Second Founding" of America. It’s the big one. It’s the reason we have birthright citizenship and the "equal protection of the laws" that lawyers argue about on the news every night. But if you're asking when was 14th amendment passed, the answer isn't just a single date on a calendar. It was a messy, high-stakes political brawl that almost didn't happen.

The short answer? Congress passed the joint resolution on June 13, 1866. But that wasn't the end. Not even close. Because it was a Constitutional amendment, it had to go to the states for ratification. That process dragged on until July 28, 1868, when Secretary of State William Seward finally certified it. Two years of arguing, threats, and literal military occupation.

The Summer of 1866: A Post-War Power Struggle

Honestly, 1866 was a weird time for the United States. The Civil War was technically over, but the country was a wreck. President Andrew Johnson—who, let’s be real, was no Abraham Lincoln—was busy fighting with the "Radical Republicans" in Congress. These guys, led by folks like Thaddeus Stevens and John Bingham, wanted to make sure the South didn't just go back to the way things were before the war.

They needed a way to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people. They needed to define what it actually meant to be an American citizen. So, Bingham started drafting the language.

By June 13, 1866, the House and Senate finally agreed on the wording. That’s the first "passed" date. But under Article V of the Constitution, Congress can't just change the law on their own. They needed three-fourths of the states to say yes. And that’s where things got incredibly complicated.

🔗 Read more: January 6th Explained: Why This Date Still Defines American Politics

Why the Ratification Took Forever

Imagine trying to get a group of people who just fought a bloody war against each other to agree on the rules for their future. It went about as well as you’d expect. Most of the Southern states flat-out rejected the amendment at first. They hated Section 1 (the citizenship part) and they really hated Section 3 (the part that banned former Confederates from holding office).

Because the Southern states said no, Congress did something pretty bold. They passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867.

Basically, they told the Southern states: "You want to be part of the Union again? You want your representatives back in D.C.? Then you must ratify the 14th Amendment." It was essentially ratification at gunpoint. You had military governors overseeing these states until they fell in line.

- Connecticut was the first to jump on board (June 25, 1866).

- New Hampshire and Vermont followed quickly.

- By early 1867, it looked like a stalemate.

- Then, under pressure, Arkansas, Florida, and North Carolina flipped in mid-1868.

The Drama of July 1868

By the time July 1868 rolled around, the math was getting close. But then, two states—Ohio and New Jersey—tried to "un-vote." They had already ratified it, but then their state legislatures flipped parties and they tried to withdraw their approval.

💡 You might also like: Is there a bank holiday today? Why your local branch might be closed on January 12

Secretary of State William Seward was in a tough spot. He wasn't sure if a state could legally take back a ratification. On July 20, 1868, he issued a sort of "maybe" proclamation. He said, "Well, if Ohio and New Jersey still count, then we have enough." Congress wasn't having it. They passed a concurrent resolution the next day declaring the 14th Amendment a valid part of the Constitution, regardless of what Ohio and New Jersey thought.

Finally, on July 28, 1868, Seward issued the official certification. That is the date most historians point to as the moment the 14th Amendment became the "Law of the Land."

What Most People Get Wrong About Section 1

When people look up when was 14th amendment passed, they’re usually thinking about the Due Process Clause or Equal Protection. We think of it as this grand declaration of human rights. But at the time, a lot of the focus was actually on Section 4—making sure the federal government didn't have to pay for the South's war debts. Money, as usual, played a huge role.

Another thing? It didn't give women the right to vote. In fact, Section 2 of the 14th Amendment actually introduced the word "male" into the Constitution for the first time when discussing voting rights. This absolutely infuriated suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They felt betrayed by the very people they had worked with in the abolitionist movement.

📖 Related: Is Pope Leo Homophobic? What Most People Get Wrong

The Long Shadow of the 1860s

The 14th Amendment stayed "dormant" for a long time. For decades after it was passed, the Supreme Court actually used it more to protect corporations than to protect individuals. It wasn't until the mid-20th century, during the Civil Rights Movement, that the "Equal Protection" part started being used the way we see it today. Cases like Brown v. Board of Education or Obergefell v. Hodges (the same-sex marriage case) all hinge on those sentences written back in 1866.

It’s a bit wild to think that a law passed to solve a post-Civil War crisis is still the most litigated part of the Constitution in 2026.

Actionable Steps for Understanding the 14th Amendment

If you really want to understand the impact of when the 14th Amendment was passed, don't just read a summary. Go to the source.

- Read the Five Sections: Most people only know the first paragraph. Read the whole thing. Section 3 (the disqualification clause) has been a massive topic in recent legal challenges regarding federal elections.

- Check Your State's History: Look up when your specific state ratified the amendment. You might be surprised to find your state was one of the holdouts—or one of the ones that tried to take it back.

- Research the "Slaughter-House Cases": If you want to see how the Supreme Court almost gutted the 14th Amendment just five years after it was passed, look into the 1873 Slaughter-House Cases. It shows how fragile these rights were from the start.

- Visit the National Archives Online: They have high-resolution scans of the original documents and the letters from the states. Seeing the actual handwritten ratifications makes the history feel much more "real" than a textbook ever could.

The 14th Amendment wasn't just a piece of paper. It was the result of a second American Revolution—one that happened in the halls of Congress and the statehouses of a broken nation. Knowing it was passed in 1868 is a start, but understanding the fight to get it there is the real story.