George Orwell didn't go to Spain to write a masterpiece. He went to kill fascists. That sounds blunt, maybe even a bit startling, but it's the raw truth behind Homage to Catalonia George Orwell. When he stepped off the train in Barcelona in late 1936, he wasn't looking for a literary hook or a Pulitzer. He was looking for a rifle. What he found instead was a city where the working class was actually in the driver's seat, a place where "sir" and "don" had vanished, and where the very air felt like a revolution.

It changed him. It also nearly killed him.

Most people know Orwell for the grim, gray hallways of 1984 or the talking pigs of Animal Farm. But you can't really understand those books without digging into his time in Spain. Homage to Catalonia George Orwell is the bridge between his early work and his late-career genius. It's a memoir that reads like a thriller, yet it’s packed with the kind of political heartbreak that stays with you long after you’ve put the book down.

The Barcelona Dream and the Reality of the Trenches

Barcelona was a shock. Honestly, Orwell describes it as something almost hallucinatory. The walls were plastered with revolutionary posters, the churches had been gutted, and tipping was banned because it was seen as an insult to equality. For a guy who grew up in the rigid, class-obsessed world of Edwardian England, this was intoxicating. He joined the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista) militia, mostly by chance, and headed to the front lines.

The war wasn't all glory. Mostly, it was mud.

Orwell spends a huge chunk of the book talking about the sheer, mind-numbing boredom of the trenches. It wasn't constant gunfire; it was lice. It was the lack of firewood. It was the "rotten" food and the fact that most of the weapons were ancient Mausers that jammed more often than they fired. He writes about the "essential horror of army life" being the lack of sleep and the constant, biting cold of the Spanish winter. You get the sense that he’s trying to strip away the romanticism that usually coats war stories. It’s gritty. It’s dirty. It’s real.

But then, the atmosphere shifted.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

The Republican side—the side Orwell was fighting for—started eating itself. While the fascists under Franco were unified and receiving massive aid from Hitler and Mussolini, the anti-fascists were busy arguing about whether to win the war first or finish the revolution first. This is where the book stops being a simple war memoir and becomes a terrifying political autopsy.

Why Homage to Catalonia George Orwell Is a Warning About "Truth"

By May 1937, the vibes in Barcelona had turned sour. Orwell returned from the front for a bit of leave, only to find himself caught in the middle of a "war within a war." This is the famous May Days. Street fighting broke out, not against the fascists, but between different factions of the Republican side—specifically the Communists (backed by the Soviet Union) and the Anarchists/POUM (who Orwell was with).

This is the pivotal moment of the book.

Orwell watched as the Communist-controlled press started labeling his friends—men he had bled with in the trenches—as "Trotskyist-fascists" and secret spies for Franco. It was a lie. A total, manufactured, calculated lie. He saw how easily the truth could be manipulated by people in power.

"I saw history being written not in terms of what happened, but of what ought to have happened according to various 'party lines'."

That realization is the DNA of 1984. When you read about "Doublethink" or "Newspeak," you're looking at Orwell’s trauma from Spain being processed through fiction. He saw the Soviet Union’s influence in Spain as a creeping totalitarianism that cared more about control than defeating fascism. He was hunted. He had to sleep in bombed-out ruins and hide in the shadows because the secret police were rounding up anyone associated with the POUM.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

His wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy, was actually in Barcelona with him, and her role is often undersold. She was essentially running a logistics hub and risk assessment for him while he was dodging bullets and secret agents. They eventually had to flee the country, slipping across the French border just ahead of the police.

The Bullet in the Throat

We have to talk about the moment Orwell got shot. It’s one of the most famous passages in 20th-century non-fiction. He was standing in a trench, talking to some soldiers, and then—snap.

He describes it as a feeling of being at the center of an explosion. No pain, just a massive shock and a sensation of "shattering." A fascist sniper had hit him clean through the throat. It’s a miracle he survived. The bullet missed his carotid artery by a fraction of an inch. For a while, he lost his voice, and his arm went numb.

The irony? Even while he was recovering from a near-fatal wound sustained fighting fascists, the papers in Barcelona were still calling him a traitor.

That’s the core of the Homage to Catalonia George Orwell experience. It’s the realization that you can be a hero on the battlefield and a villain in the headlines at the exact same time, depending on who owns the printing press. It’s a terrifying thought. Honestly, it’s a thought that feels more relevant today than it did in 1938.

The Legacy of a "Failure"

When the book was first published, it was a total flop. Seriously. It sold fewer than 1,000 copies in its first few years. The Left hated it because it criticized the Soviets. The Right didn't care because it was written by a socialist. Orwell died before the book ever became a classic.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

But it survived. It survived because it’s one of the most honest accounts of political disillusionment ever written. Orwell didn't stop being a socialist after Spain; if anything, he became more committed to what he called "Democratic Socialism." But he became a fierce enemy of any system—left or right—that tried to crush the individual spirit or rewrite the past.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Reader

If you're picking up the book for the first time, or even if you've read it and want to dive deeper into the history, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Context is everything. Read up on the difference between the CNT-FAI (Anarchists) and the PSUC (Communists). The book makes way more sense once you realize it's a three-way fight, not just two sides.

- Look for the "Orwellian" seeds. Pay attention to how the newspapers describe the street fighting in Barcelona. You can see the blueprints for the Ministry of Truth being drawn in those chapters.

- Don't skip the "boring" political chapters. Orwell actually suggests readers skip the heavy political analysis chapters if they just want the story. Don't do it. Those chapters (specifically Chapter 5 and Chapter 11) are where the real meat of his argument lies.

- Verify the sources. If you want to see how deep the rabbit hole goes, look into the work of historian Antony Beevor or Hugh Thomas. They back up a lot of what Orwell reported, even the stuff that seemed like "conspiracy" at the time.

Homage to Catalonia George Orwell is a messy book about a messy war. It doesn't have a happy ending. The Republic lost, Franco won, and Orwell went home with a damaged voice and a heavy heart. But in telling the truth about the "betrayal" in Barcelona, he gave us a toolkit for spotting propaganda in our own lives. He taught us that the most revolutionary thing you can do is report what you actually see, even when it’s inconvenient for your "side."

The book is more than a history lesson. It's a manual for mental survival. Next time you see a headline that seems a little too convenient, or a political narrative that ignores the facts on the ground, think about Orwell in the trenches of Huesca. Think about the man who almost died for a cause and then had the courage to tell the world that his own side was lying. That’s the real homage.

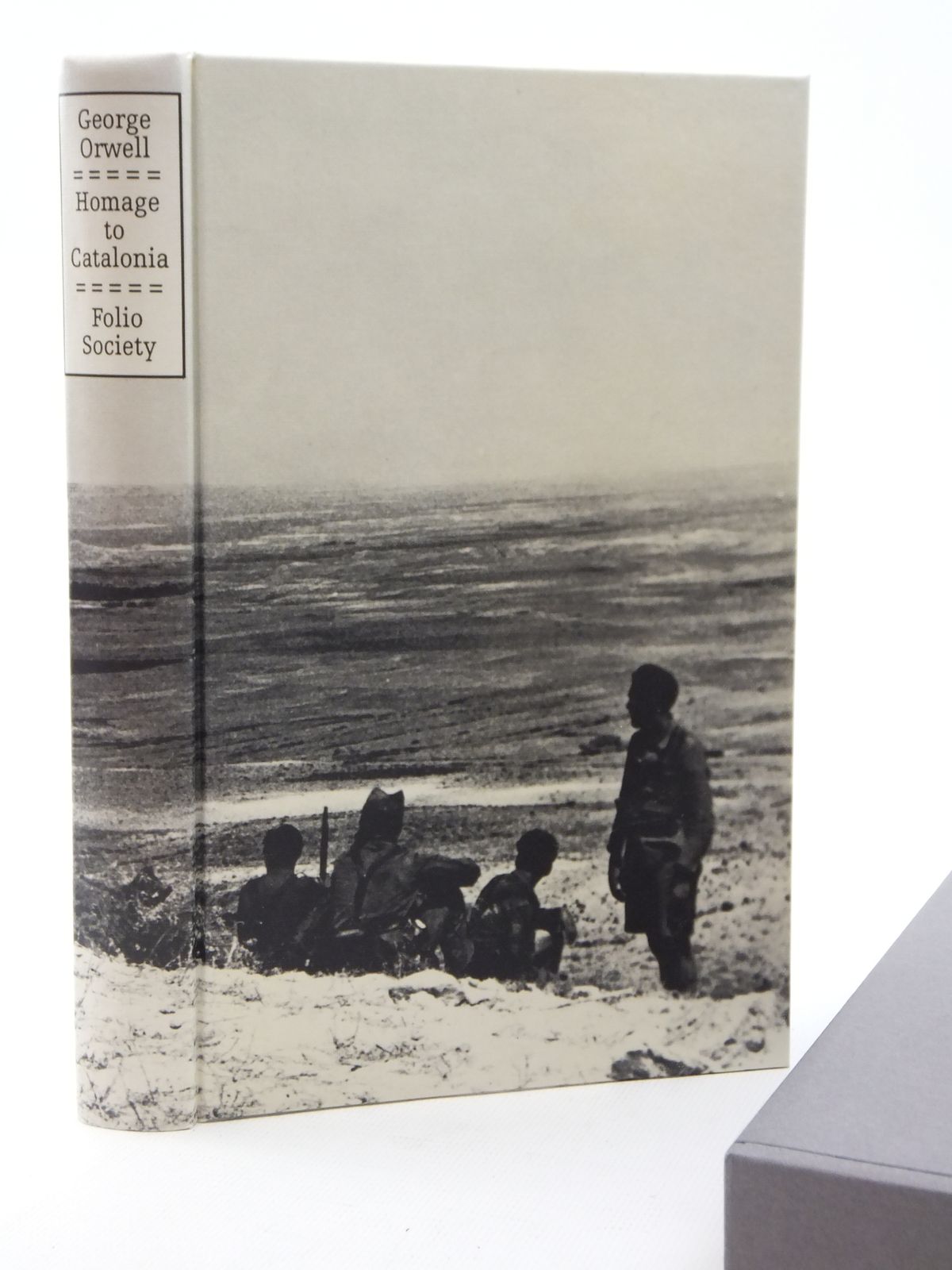

Start by grabbing a copy of the Penguin Classics edition—it includes some of Orwell’s later essays on the war that provide even more clarity. Or, if you’re in Barcelona, take the "Orwell Walk." You can still see the bullet holes in the walls of the Plaça de Sant Felip Neri and visit the Hotel Falcón where the POUM used to hang out. Seeing the physical locations makes the text hit twice as hard.