By August 1793, Philadelphia was the crown jewel of the United States. It was the nation’s temporary capital, a bustling port, and basically the most sophisticated city in the Americas. Then, people started dying. Not just a few people, but hundreds, then thousands, in a horrific, bloody fashion that no one understood. The yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia 1793 wasn't just a health crisis; it was an existential threat that almost strangled the young American government in its crib.

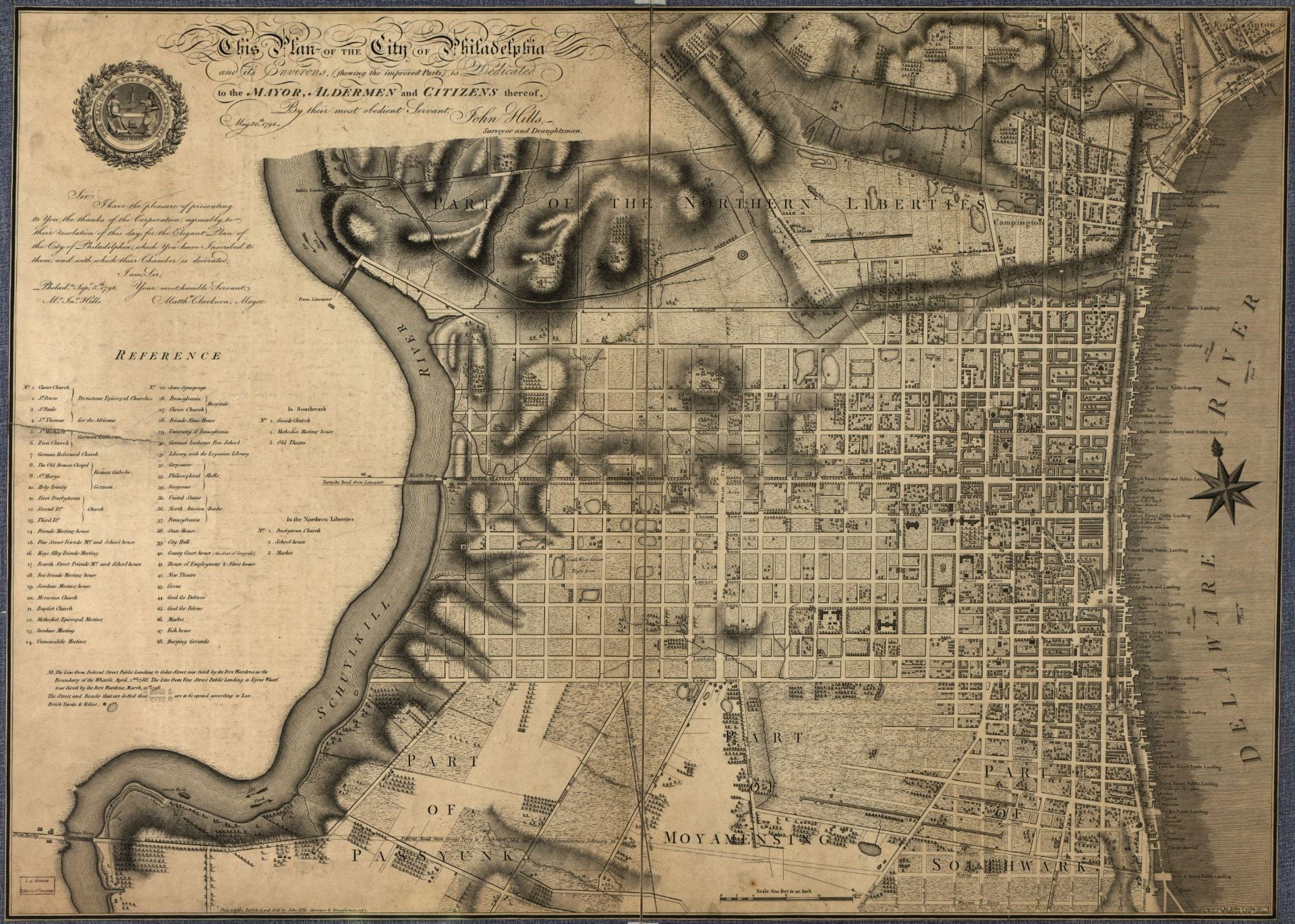

It started near the Water Street wharves. The air was thick, humid, and honestly disgusting. Dead fish and rotting vegetable matter—specifically a large shipment of damaged coffee—were blamed for the "miasma" or foul air. We know now that the culprit was actually the Aedes aegypti mosquito, but back then, the science just wasn't there. People were looking at rotting coffee while the real killers were buzzing right past their ears.

The Symptoms and the Terror

Imagine waking up with a headache. A few hours later, you're shivering with chills. By day three, your skin and eyes turn a haunting shade of yellow as your liver fails. Then comes the "black vomit." This was the most terrifying part for observers. It was partially digested blood, a sign of internal hemorrhaging. It’s hard to overstate how much this broke the city's spirit.

Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the most famous doctor in the country, was right in the thick of it. He stayed while others fled. But, and this is a big "but," his treatments were controversial even then. He believed in "heroic medicine." This basically meant aggressive bloodletting and massive doses of calomel (mercury) to purge the system.

Some patients probably survived despite his help, not because of it.

On the other side of the medical fence was Jean Devèze. He was a French doctor who had seen the fever in the West Indies. He took a much milder approach: rest, fluids, and cleanliness. At the Bush Hill estate, which had been converted into a makeshift hospital, Devèze’s methods actually saw higher survival rates than Rush’s aggressive bleeding. It was a classic clash between established dogma and practical observation.

📖 Related: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

A City in Flight

When the death toll started climbing, anyone with money got out. Fast.

President George Washington packed up and headed to Mount Vernon. Thomas Jefferson left. Alexander Hamilton stayed a bit longer but eventually caught the fever himself (he survived, likely thanks to the more moderate "French" treatment). About 17,000 people—roughly 40% of the population—fled the city.

The ones left behind were the poor, the desperate, and the brave.

The Role of the Free African Society

One of the most incredible, and often overlooked, parts of the yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia 1793 is the role played by the city's Black community. Benjamin Rush mistakenly believed that Black people were immune to the fever. He was wrong. But based on that belief, he asked Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, leaders of the Free African Society, to help mobilize their community to nurse the sick and bury the dead.

They did it. They stepped up when the city’s white infrastructure had collapsed.

👉 See also: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

They weren't just "helpers." They were the front line. They walked into plague-infested homes, cleaned up the black vomit, and provided comfort to the dying. Later, when they were unfairly accused of profiteering during the crisis, Jones and Allen published a brilliant defense—the first copyrighted pamphlet by Black authors in America—to set the record straight. They proved that their community had acted with more civic virtue than many of the wealthy citizens who had bolted for the countryside.

Why Philadelphia?

You might wonder why it hit so hard there. It was a perfect storm.

- The Weather: 1793 was an unusually hot and dry year, but with enough stagnant water in rain barrels and gutters for mosquitoes to breed.

- The Trade: Refugees from a revolution in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) arrived in Philadelphia that summer. They brought the virus in their blood and the mosquitoes in the holds of their ships.

- The Infrastructure: There was no organized trash collection or sewage system. The city was a literal breeding ground.

By the time October rolled around, the city was a ghost town. The bells of Christ Church, which usually tolled for every death, stopped ringing because the constant chiming was driving the survivors insane. People walked in the middle of the street to avoid passing too close to houses where someone might be dying. Friendships ended at the doorstep. Even family members sometimes abandoned each other.

The Frost That Saved the City

There was no vaccine. There was no cure. What stopped the yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia 1793 was quite literally the weather.

In late October and early November, a series of hard frosts hit the city. The mosquitoes died. The transmission cycle broke. Suddenly, the daily death counts dropped from 100 to single digits. People started trickling back from the countryside. George Washington returned. The shops reopened.

✨ Don't miss: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

But the scars were deep.

Around 5,000 people had died. In a city of 50,000, that’s 10% of the population gone in a single season. If that happened in a modern city like New York today, we’d be talking about nearly a million deaths in three months.

Lessons for Modern Public Health

Looking back at 1793, it's easy to feel superior because we know about viruses and vectors. But the human reaction—the fear, the misinformation, the political infighting—looks remarkably familiar.

The crisis forced Philadelphia to get serious about public health. It led to the creation of a permanent Board of Health and better sanitation laws. It also highlighted the massive divide between those who can afford to "social distance" (by moving to a country estate) and those who have to keep the city running.

If you’re researching this period, don’t just look at the death tolls. Look at the diaries. Elizabeth Drinker’s diary is a goldmine for understanding the day-to-day anxiety of a family trying to survive the plague. It wasn't just a historical event; it was a collective trauma that reshaped the American capital and the way we think about urban living.

Actionable Takeaways from the 1793 Crisis

If you're a history buff or a student of public health, here is how you can actually use this information to understand the period better:

- Compare Treatments: Research the "French" vs. "American" medical schools of the 1790s. It’s a fascinating look at how medical authority is built and destroyed during a crisis.

- Visit the Sites: If you’re in Philadelphia, go to the Arch Street Meeting House or Christ Church. Seeing the physical proximity of these places makes the speed of the spread much more real.

- Read the Primary Sources: Don't just take a textbook's word for it. Read A Short Account of the Malignant Fever by Mathew Carey (published in late 1793) alongside Jones and Allen’s rebuttal. It shows you exactly how narrative and "fake news" were contested even back then.

- Study the Vector: Look into the Aedes aegypti mosquito. It’s still a major health threat globally today, carrying Dengue and Zika. The 1793 epidemic wasn't a one-off; it was part of a global history of tropical diseases moving through trade routes.

The 1793 epidemic reminds us that even the strongest societies are fragile. It wasn't the government that saved Philadelphia; it was the onset of winter and the tireless work of volunteers who stayed behind when the leaders fled. It's a messy, tragic, and ultimately human story that still defines the city’s character today.