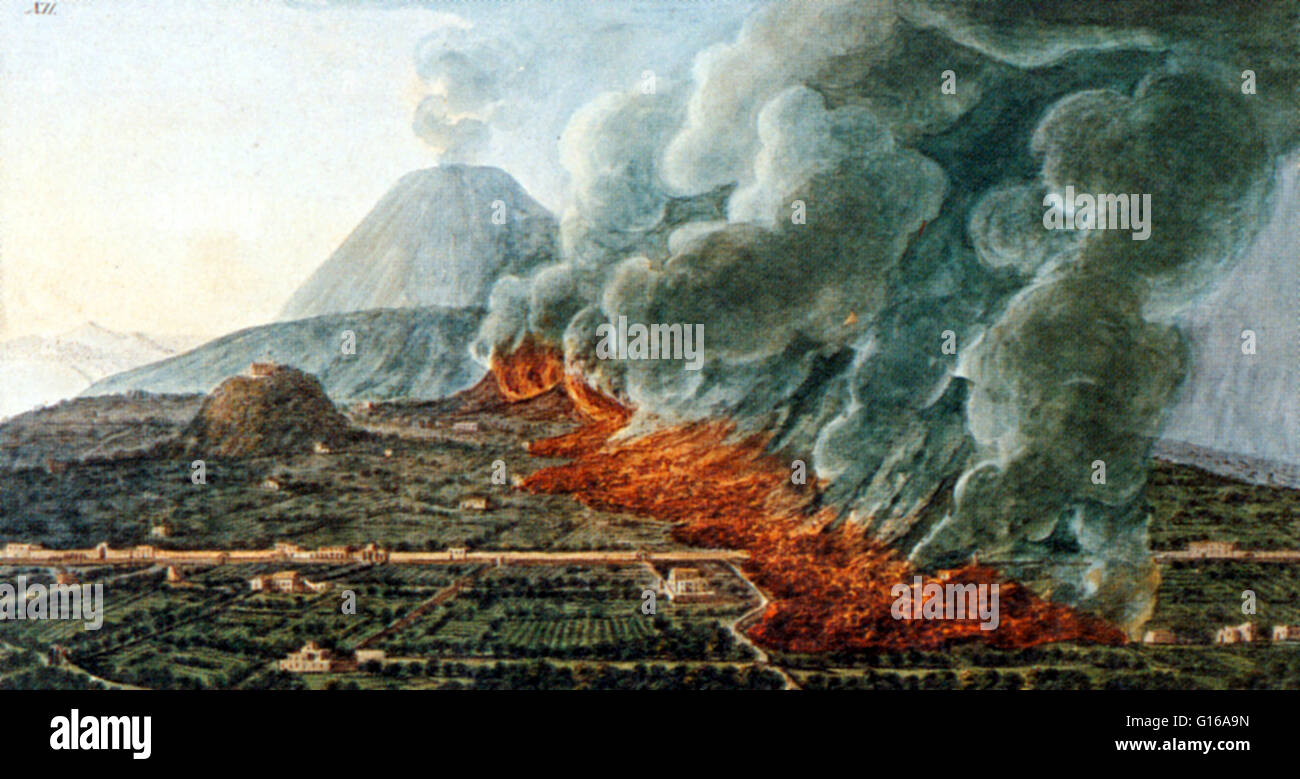

Honestly, the way we talk about the Mt Vesuvius Pompeii eruption 79 AD usually feels like a movie script. We imagine a sudden boom, a wall of lava, and people frozen instantly like statues. But the reality was a lot messier, slower, and arguably more terrifying because people had plenty of time to make the wrong decisions.

It wasn't just a single explosion. It was a multi-day nightmare.

The city of Pompeii didn't actually sit at the base of a "volcano" as the residents understood it. To them, Vesuvius was just a big, green, fertile hill. They’d had earthquakes for years—including a massive one in 62 AD that nearly leveled the town—but they just kept rebuilding. They didn't have a word for "volcano." The ground shook, the wells ran dry, and the dogs barked, but life in a busy Roman port city was too profitable to leave just because of some tremors.

The Day the Sky Turned to Stone

Around noon on August 24 (or possibly October 24, depending on which modern archaeologists you ask), the top of the mountain simply disintegrated. It didn't flow; it blew. It sent a column of ash and pumice 20 miles into the stratosphere.

Pliny the Younger, who watched the whole thing from across the Bay of Naples at Misenum, described it as looking like a "pine tree." He meant the Mediterranean stone pine, with its long trunk and flat, spreading top. It’s the most famous eyewitness account in history. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, died trying to rescue people. He was a naval commander and a bit of a scientist, and he basically sailed right into the teeth of the beast because he wanted to see it up close and save his friends.

For the first eighteen hours, it just rained rocks. Small, light rocks called lapilli.

You might think you could survive that. And many did. People stayed in their houses, thinking the walls would protect them. But the weight of the ash was the silent killer. Roman roofs weren't built for snow, let alone thousands of tons of volcanic stone. They started collapsing, crushing families who thought they were safe indoors. If you stayed, you died. If you ran, you had to navigate total darkness with a pillow tied to your head for protection, tripping over neighbors in the street.

Those Famous "Statues" Aren't What You Think

We've all seen the haunting photos of people curled up, frozen in their final moments. It’s important to clarify something: those aren't the actual bodies.

🔗 Read more: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

When the Mt Vesuvius Pompeii eruption 79 AD finished its work, the city was buried under 20 feet of debris. Over centuries, the organic matter—the skin, the clothes, the muscles—rotted away. This left hollow cavities in the hardened ash. In the 1860s, an archaeologist named Giuseppe Fiorelli realized he could pump liquid plaster into these holes. When the plaster hardened and the surrounding ash was chipped away, it revealed the exact shape of the person at the moment of death.

It’s chilling. You see the folds in their tunics. You see a dog on its back, struggling against its chain.

The actual cause of death for these people wasn't "suffocation" by ash as previously thought. Recent studies led by experts like Pier Paolo Petrone at the University of Naples Federico II suggest many died from extreme thermal shock. We're talking about pyroclastic surges—clouds of gas and dust moving at 200 miles per hour at temperatures over 500 degrees Fahrenheit. It was so hot that, in some cases, victims' skulls literally exploded because the fluids inside boiled instantly.

Basically, they were gone before they even knew the surge hit them.

The Herculaneum Difference

If Pompeii was a tragedy of falling rocks, Herculaneum was a tragedy of heat.

Herculaneum was a wealthier, smaller seaside town to the west. Because of the wind patterns, it didn't get the heavy rain of pumice that Pompeii did. For hours, the residents thought they were the lucky ones. They gathered on the beach, inside arched brick boat sheds (fornici), waiting for rescue by sea.

They waited too long.

💡 You might also like: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

When the eruption column finally collapsed, it sent a pyroclastic flow straight down the mountain. It buried Herculaneum in 60 feet of mud and ash. When archaeologists finally reached the boat sheds in the 1980s, they found hundreds of skeletons huddled together. The heat was so intense it carbonized wood and even food. We've found actual charred loaves of Roman bread and carbonized scrolls that researchers are now trying to read using X-ray phase-contrast tomography.

Why the Date is Such a Huge Mess

For a long time, every textbook said August 24, 79 AD.

But if you visit Pompeii today, the guides will tell you that's likely wrong. It was probably autumn. Why? Because archaeologists keep finding things that don't belong in August. They found braziers filled with charcoal for heating. They found people wearing heavy wool clothing. They found autumnal fruits like pomegranates and walnuts on the ground.

The clincher was a bit of charcoal graffiti found in 2018. It was dated "the sixteenth day before the calends of November," which translates to October 17. Since charcoal is erasable, it must have been written just days before the eruption. This changes our entire understanding of the event. It means the "August" date was likely a transcription error made by monks copying Pliny’s letters centuries later.

What Pompeii Tells Us About Being Human

The city is a time capsule, but not a perfect one. It’s a messy, beautiful, slightly gross look at Roman life.

The walls are covered in graffiti. Not just "Caesar was here," but actual human stuff. People complained about the food at the local tavern. They wrote poems about their crushes. They left reviews of the local brothel. One of my favorite pieces of graffiti literally says, "Wall, I wonder that you have not gone smashed to pieces, who have to support the tedium of so many writers."

It reminds us that these weren't "ancients." They were us.

📖 Related: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

They loved fast food—we’ve found dozens of thermopolia, which were basically snack bars with holes in the counters for jars of hot stew. They had "Beware of the Dog" mosaics in their entryways. They were obsessed with status, decoration, and politics.

The Danger Hasn't Actually Gone Away

Vesuvius is still one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world.

It’s an active stratovolcano. The last major eruption was in 1944, during World War II, which destroyed several villages and damaged a fleet of Allied bombers. Today, about 3 million people live in the immediate vicinity. The "Red Zone"—the area that would need to be evacuated immediately in a major event—is home to 600,000 people.

The Italian government actually offers people money to move out of the Red Zone. Not many take it. The soil is too rich, the view is too good, and the human brain is remarkably good at saying, "It won't happen to me."

How to Actually See the History

If you’re planning to visit the site of the Mt Vesuvius Pompeii eruption 79 AD, don't just do a day trip from Rome and rush through it. You'll miss the soul of the place.

- Go to the National Archaeological Museum in Naples first. This is non-negotiable. Almost all the good stuff—the mosaics, the statues, the "Secret Cabinet" of erotic art—was moved there for protection. If you only see the ruins, you're seeing the skeleton; the museum is the skin.

- Visit Herculaneum (Ercolano). It’s smaller, better preserved, and much less crowded. You can see two-story houses and actual wooden furniture that survived.

- Hike the crater. You can take a bus partway up Vesuvius and then hike to the rim. Looking down into the vent and then looking out over the densely packed streets of modern Naples puts the scale of the 79 AD disaster into perspective.

- Look for the "Garden of the Fugitives." This is where 13 casts of victims are located in an old vineyard. It’s one of the most sobering spots in Pompeii.

The story of 79 AD isn't about a mountain. It’s about a society that was so convinced of its own permanence that it ignored the literal ground screaming beneath its feet. We study it not just for the history, but as a reminder that the world can change in a single afternoon.

Next Steps for Your Trip or Research:

- Check the official Pompeii Sites website for "unlocked" villas. They rotate which houses are open to the public to prevent wear and tear.

- Download the "Pompeii Sites" app before you go; cellular data is notoriously spotty inside the ruins.

- Read "The Shadow of Vesuvius" by Daisy Dunn for a modern, deeply researched look at the lives of the Plinys and the cultural impact of the disaster.

- Book a certified guide if you're visiting in person. The site is a labyrinth, and without context, it just looks like a lot of broken bricks. Look for guides specifically certified by the Campania region.