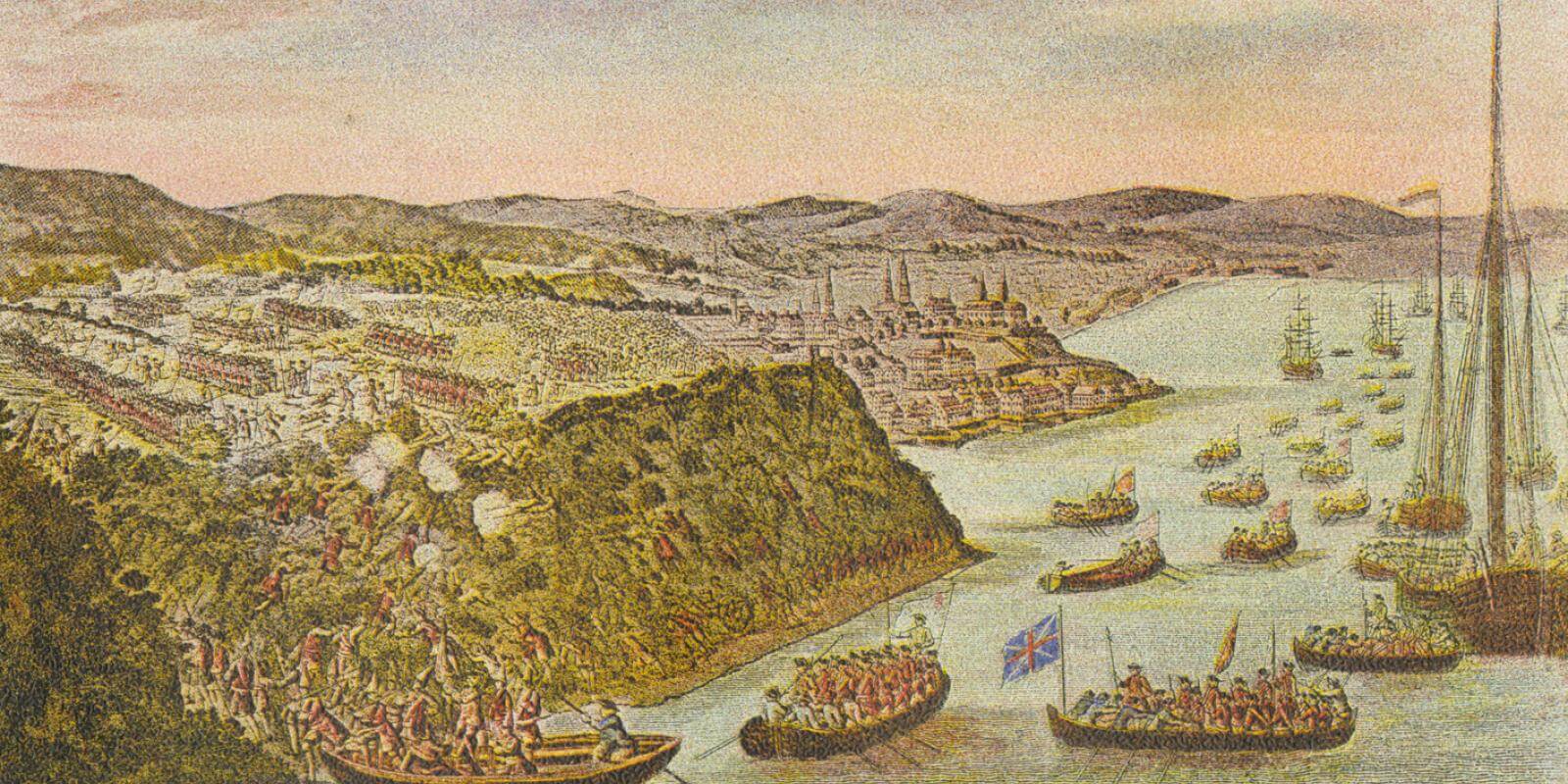

History is usually a slow burn. It's decades of policy, years of tension, and months of maneuvering. But sometimes, everything flips in the time it takes to eat a sandwich. The Battle of Quebec City, fought on September 13, 1759, is basically the ultimate example of that. It wasn’t some epic, weeks-long siege that ended in a dramatic final stand. It was a chaotic, bloody, and surprisingly short mess on a farmer’s field called the Plains of Abraham.

Most people think of Canada as this inherently bilingual, peaceful mosaic, but that whole identity was forged in a fifteen-minute window of absolute terror. If you've ever walked the streets of Old Quebec, you've felt the weight of it. The stone walls aren't just for show. They were built because the British and the French were locked in a global "Seven Years' War" that was essentially World War Zero.

The Impossible Climb and the General’s Gamble

James Wolfe was a mess. The British General was chronically ill, probably suffering from tuberculosis or kidney stones, and he was under massive pressure to produce a win before the harsh Canadian winter froze his fleet into the St. Lawrence River. He had been staring at the cliffs of Quebec for months, unable to find a way in. The Marquis de Montcalm, the French commander, knew he just had to wait Wolfe out. If the river froze, the British had to leave.

Wolfe decided on a "Hail Mary" pass.

He spotted a small cove called Anse-au-Foulon. It had a narrow path leading up the steep cliffs. On the night of September 12, British troops drifted downriver in total silence. They didn't use oars; they just let the current take them. When a French sentry challenged them in the dark, a Highland officer who spoke perfect French answered back, tricking the guard into thinking they were a French food convoy. It was a classic ruse.

By dawn, Montcalm woke up to a nightmare. There were 4,500 British redcoats standing in a double line on the Plains of Abraham, right outside his front door.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

Honestly, Montcalm’s reaction is still debated by historians today. He had troops scattered all over the region. He could have waited for reinforcements. He could have stayed behind the city walls. Instead, he decided to attack immediately. Maybe he was panicked. Maybe he thought the British hadn't finished landing their artillery. Whatever the reason, he marched his men out to meet them in the open.

Why the Battle of Quebec City Was Won on Discipline

The French army was a mix of regular soldiers, Canadian militia, and Indigenous allies. They were great at "petite guerre"—skirmishing and woods fighting—but they weren't used to the rigid, European-style line warfare that Wolfe favored. As the French advanced, they started firing too early. Their lines got ragged. They were shouting, tripping over the uneven ground of the farmer's field, and losing cohesion.

The British? They just stood there.

Wolfe had ordered his men to double-load their muskets with two balls instead of one. They waited until the French were barely 40 yards away. You could see the buttons on their coats. Then, the British fired a volley that was so synchronized it reportedly sounded like a single cannon blast.

It was a massacre.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

The French line shattered instantly. The "Battle of Quebec City" was effectively decided in those first few minutes. The British then drew their claymores and swords, charging into the smoke. It was loud, it was smelly, and it was over before most of the city even knew it had started.

Both Generals Died, Which is Pretty Rare

You don't often see both opposing commanders die in the same engagement. Wolfe was hit three times—once in the wrist, once in the stomach, and finally in the chest. He lived just long enough to hear that the French were on the run. His last words were reportedly, "Now, God be praised, I will die in peace."

Montcalm didn't fare much better. He was hit by a musket ball while retreating on horseback. He was carried back into the city and died the next morning. He’s buried in a crater created by a British shell inside the Ursuline Convent. There's a certain grim symmetry to it. Two brilliant, tired men dying for a piece of high ground that would dictate the fate of a continent.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Aftermath

There's this myth that the French just packed up and left after the Battle of Quebec City. Not even close. The French actually won a follow-up battle at Sainte-Foy the next spring. They almost took the city back! But when the first ships appeared on the St. Lawrence after the ice melted, they were flying British flags. That was the real "game over" moment.

The significance of this battle isn't just about who won a fight. It's about the Treaty of Paris (1763). France basically traded all of "New France" to Britain so they could keep their sugar islands in the Caribbean (Guadeloupe and Martinique). At the time, sugar was worth more than a frozen wilderness.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

This decision fundamentally created the Canada we know. The British suddenly had to figure out how to rule 70,000 French-speaking Catholics. Instead of forcing them to change, the British passed the Quebec Act of 1774, which allowed the French to keep their language, their religion, and their civil law.

That act was a huge reason why Canada didn't join the American Revolution. The French Canadians looked at the anti-Catholic sentiments in the 13 Colonies and decided they were actually safer under the British Crown. If Wolfe hadn't climbed those cliffs, there’s a very good chance North America would look like a giant version of the United States today.

Visiting the Site Today: A Reality Check

If you go to the Plains of Abraham today, it’s a beautiful park. People jog there. There are outdoor concerts. It’s hard to reconcile the joggers in neon spandex with the image of thousands of men bleeding out in the mud.

- The Martello Towers: The British built these circular forts after the battle because they were terrified the French (or the Americans) would try the same trick they did.

- The Joan of Arc Garden: It's stunning, but it sits right near where some of the heaviest fighting happened.

- The Citadelle: It’s a massive star-shaped fort that came later, but it shows how Quebec became the "Gibraltar of the North."

Acknowledge the complexity when you visit. This wasn't a "good guys vs. bad guys" situation. It was two empires clashing over resources, and the people caught in the middle—the French settlers and the Indigenous nations like the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq—had to navigate the fallout for centuries.

How to Actually Explore This History

To really get your head around the Battle of Quebec City, don't just read a plaque. Do these three things to see the tactical reality of 1759:

- Walk the Governor's Promenade: Start at the Château Frontenac and walk along the cliffs toward the Plains. You'll quickly realize how insane it was to try and scale those heights in the dark.

- Visit the Musée de la civilisation: They often have exhibits that show the Indigenous perspective of the war, which is usually ignored in the "Wolfe vs. Montcalm" narrative.

- Check the "Lines of Fire" Exhibit: Located at the Plains of Abraham Museum, it uses immersive tech to show how the musket volleys actually worked. It’s the best way to understand how 15 minutes changed the map of the world.

The battle didn't just end a war. It started the long, complicated process of figuring out how two different cultures could live in the same house. We're still working on that one.