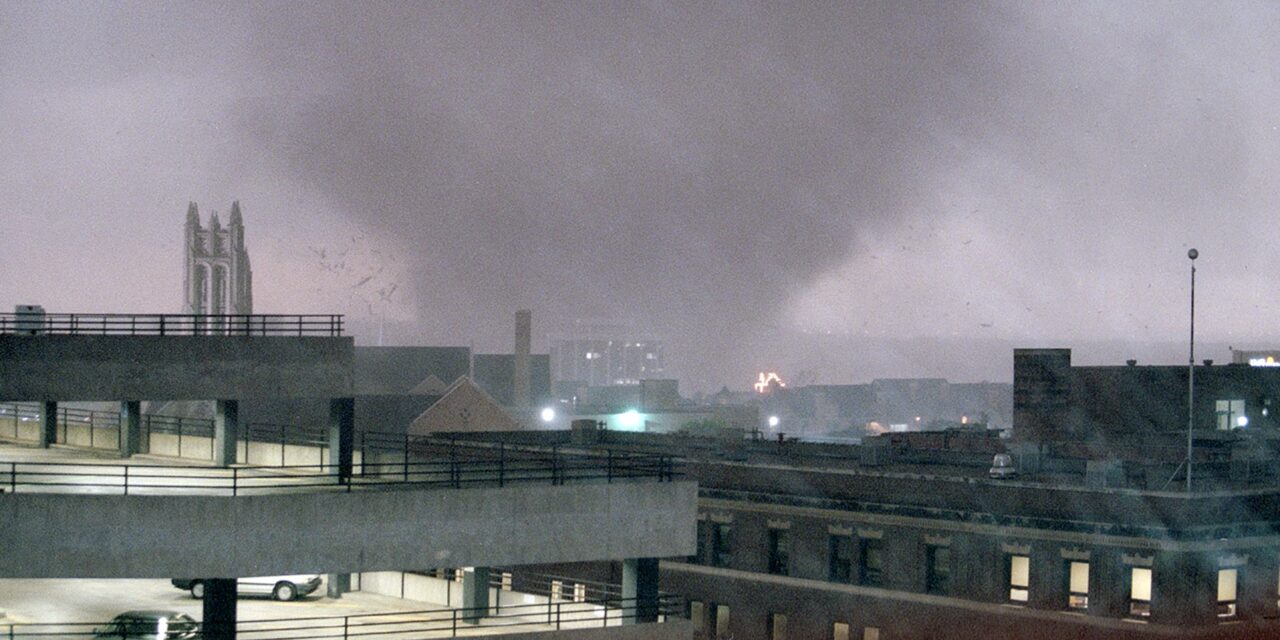

March 28, 2000, started out like any other humid spring afternoon in North Texas. People were finishing up work in the gleaming glass towers of downtown, and the usual rush hour crawl was beginning on I-30. Then the sky turned that weird, bruised shade of green that makes every Texan's stomach drop. By 6:15 PM, a massive F3 wedge was tearing through the heart of the city. It wasn't just a storm; the 2000 Fort Worth tornado became a defining moment for modern urban disaster management.

Most people think of tornadoes as rural monsters that chew up cornfields and barns. This one was different. It took a direct aim at the skyline.

It’s actually kinda wild when you look at the footage now. You see the Bank One Tower—which was the city’s pride at the time—losing hundreds of windows in seconds. It looked like the building was being skinned alive. Shards of glass were flying through the air like shrapnel, turning the streets of downtown into a literal death trap. Honestly, it's a miracle the death toll wasn't in the hundreds.

The Path of Destruction: Beyond the Skyline

While the images of the broken skyscrapers are what everyone remembers, the 2000 Fort Worth tornado actually began its path of destruction further west. It first touched down near River Oaks and Castleberry High School. It was messy. It was erratic. Unlike those "pretty" stovepipe tornadoes you see on the Discovery Channel, this was a rain-wrapped beast that many people didn't even see coming until it was on top of them.

The storm tracked eastward, gaining strength as it entered the Monticello neighborhood and the Linwood area. This is where the damage got personal. Small homes were leveled. Century-old trees were snapped like toothpicks. If you talk to anyone who lived in Linwood back then, they’ll tell you about the sound—that cliché "freight train" noise that actually sounds more like the earth is being ground into a powder.

Then it hit the Upper West Side and the central business district.

The wind speeds were estimated between 158 and 206 mph. Think about that for a second. That is enough force to turn a pebble into a bullet. The Reata Restaurant, which was located on the 35th floor of the Bank One Tower (now known as The Tower), was famously trashed. Diners had to dive under tables while the exterior walls of the restaurant basically vanished. It's one of those stories that sounds like a Hollywood movie script, but it was just a Tuesday night in Tarrant County.

The Human Element and the Toll

We often get lost in the "cool" factor of storm chasing and meteorology, but we have to talk about the cost. Two people lost their lives that day. One man was killed by a collapsing wall in the Linwood area, and another was struck by a falling brick downtown while trying to help others. It could have been so much worse.

👉 See also: Chicago Snow: Why the Forecast Keeps Changing This Week

The timing was everything.

Because it happened right as the workday was ending, many office buildings were partially empty. However, the streets were full. Total damage estimates ended up hovering around $450 million. In today’s money, that’s a staggering hit to a local economy.

Why the 2000 Fort Worth Tornado Changed Everything

Meteorologists at the National Weather Service (NWS) in Fort Worth were watching the radar intensely that night. But back in 2000, we didn't have the same hyper-localized cell phone alerts we have now. You couldn't just glance at a Twitter feed or get a "push notification." You relied on the sirens and the local news anchors like Harold Taft or David Finfrock.

The 2000 Fort Worth tornado exposed some serious gaps in how cities handle skyscraper safety during high-wind events.

- Glass is a liability. The massive failure of the glass curtain walls on the Bank One Tower and the Mallick Tower led to new discussions about building codes and the use of tempered or laminated glass in urban centers.

- The "Shadow" Effect. Interestingly, a second smaller tornado (an F0) actually touched down in South Fort Worth near the same time. This "split" focus made it even harder for emergency services to coordinate in real-time.

- Urban Microclimates. Scientists began studying how the heat and physical structure of a city might influence a tornado's behavior. While the buildings didn't "stop" the tornado—a common myth—they certainly changed the debris field patterns.

The Long Road to Recovery

For years after the storm, the Fort Worth skyline looked like a gap-toothed smile. The Bank One Tower sat boarded up with plywood for ages. It was an eyesore and a constant reminder of that evening. Many people thought it would be torn down. Instead, it was eventually stripped to its concrete frame and reborn as luxury condos.

That renovation basically sparked the residential boom in downtown Fort Worth. It's a weird irony: a disaster that almost destroyed the city center ended up being the catalyst for people moving back into it.

The Reata moved to a ground-level location in Sundance Square. The Linwood neighborhood underwent massive gentrification years later, though some would argue the "soul" of that area was blown away with the storm. You see, recovery isn't just about rebuilding walls; it's about how the community reshapes itself in the vacuum left by the wind.

Lessons You Can Actually Use

If you live in "Tornado Alley"—or even if you don't—the events of March 28 offer some pretty blunt lessons. Most people die in tornadoes because of flying debris, not the wind itself. In an urban environment, that debris is glass, steel, and brick.

🔗 Read more: Longview Daily News Obituaries: What Most People Get Wrong

- Don't trust the windows. If you're in a high-rise, get to the core of the building. The elevators might seem like a good escape, but if the power cuts, you're trapped in a metal box while the building sways. Use the stairs, and stay away from the exterior skin of the building.

- The "Under the Overpass" Myth. The 2000 storm saw people trying to seek shelter under highway overpasses. Do not do this. Overpasses act as wind tunnels, actually increasing the wind speed and making you more vulnerable to being blown out or hit by debris.

- Modern Tech is a Tool, Not a Savior. We have better radar now (Dual-Pol radar is a game changer), but it still can't tell you exactly which side of the street will be hit. You need a battery-operated NOAA weather radio. Period.

The 2000 Fort Worth tornado wasn't the biggest or the deadliest storm in Texas history, but it was one of the most significant. It proved that a modern, concrete-and-steel city is still incredibly fragile when nature decides to move through. It forced us to rethink how we build, how we alert the public, and how we recover.

Actionable Steps for Storm Season

- Audit your "Safe Zone": Go to the center-most room on the lowest floor of your home or office today. If it has a window, it's not a safe zone.

- Digital Redundancy: Download a reliable radar app like RadarScope, but also keep a physical weather radio with fresh batteries.

- The Shoe Rule: It sounds silly, but if a warning is issued, put on sturdy shoes. If your house is hit, you’ll be walking over broken glass and nails. People in the 2000 storm learned this the hard way.

- Check your Insurance: Many standard policies have specific "windstorm" deductibles that are higher than your standard deductible. Verify your coverage before the sky turns green.

Fort Worth is a different city now than it was twenty-six years ago. The skyline is taller, the population has exploded, and the technology is light-years ahead. But the memory of that F3 wedge remains a sobering reminder that we're all just guests in the path of the atmosphere's power. Stay weather aware, keep your shoes handy, and never underestimate a North Texas spring afternoon.