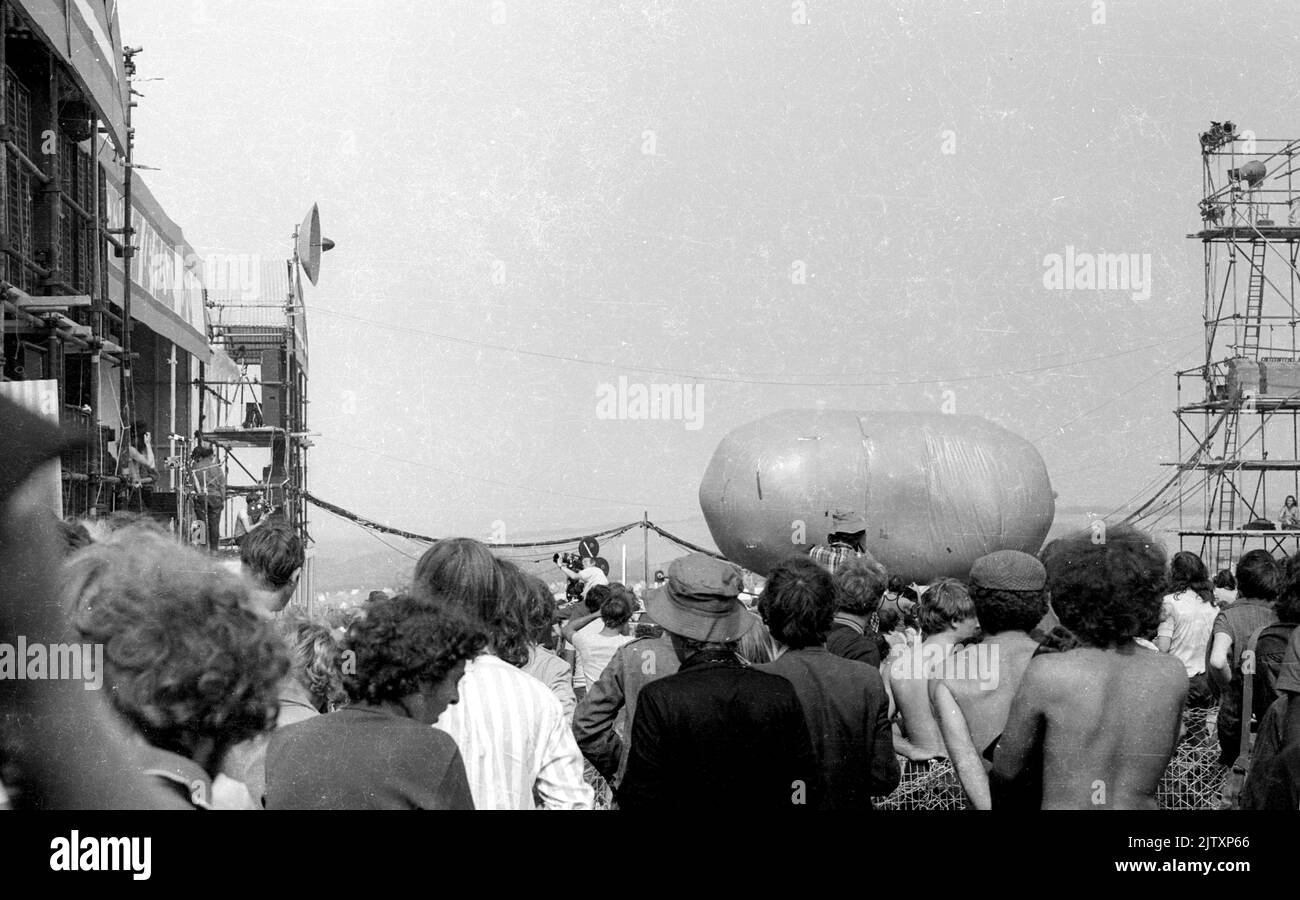

The sheer scale of it was impossible. You look at the photos now—grainy, sun-bleached shots of Afton Down—and it looks like a literal sea of humanity. People weren’t just attending a concert; they were occupying an island. It was August 1970. The "Summer of Love" was technically over, but nobody told the 600,000 people who descended on a small patch of land off the south coast of England. Honestly, the Isle of Wight 1970 festival makes Woodstock look like a quiet Sunday picnic in the park.

Estimates vary, but most historians and local authorities eventually settled on a number north of half a million. Some say 700,000. For context, the local population of the island at the time was around 100,000. It was a logistical nightmare that changed British law forever. But more than that, it was the moment the 1960s truly died, screaming and feedback-drenched, under the weight of its own impossible ideals.

The Lineup That Should Have Broken the World

If you wanted to see the gods of rock in their prime, this was the place. The bill was absurd. We're talking Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Doors, Joni Mitchell, Miles Davis, Leonard Cohen, Jethro Tull, and Ten Years After. It’s basically a Hall of Fame induction list squeezed into five days.

Jimi Hendrix’s performance is the one everyone remembers, mostly because it was his last major show before his death just weeks later. It wasn’t his best set. He was frustrated. You can hear it in the recording—radio interference was picking up on his amp, he was tired, and the crowd was a restless, churning beast. Yet, when he launched into "Machine Gun," there was still that terrifying, liquid magic. It felt like an ending.

Then you had The Who. They hit the stage at 2:00 AM on Sunday morning. Pete Townshend, wearing those iconic white boiler suits, later described the event as a "disaster." But for the fans? It was transcendental. They played Tommy in its entirety. The sheer volume of their PA system was enough to shake the foundations of the nearby villages. It was loud. Brutally loud.

✨ Don't miss: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Why the "Devastation Hill" Controversy Still Matters

Here is where the "free festival" movement hit a brick wall. The promoters, Ron and Ray Foulk of Fiery Creations, had built a massive fence to ensure people paid for their tickets. The counter-culture didn't like that. Groups like the "White Panthers" and various anarchist factions argued that music should be free.

They took up residence on a hill overlooking the arena, which they cheekily dubbed "Devastation Hill." From there, they could see the stage for free, and they spent a good portion of the weekend encouraging the paying crowd to tear down the fences. It got ugly. There were fires. There was screaming. At one point, Joni Mitchell was interrupted mid-set by a man named Yosemite Sam who grabbed the microphone to rant about the "hippie camp" being built in the background.

Joni, visibly shaken, told the crowd they were acting like "tourists" and pleaded for some respect. It was a stark reminder that the "peace and love" vibe was curdling. You've got to understand the tension: on one side, you had businessmen trying to recoup a massive investment; on the other, a generation that felt entitled to the art they consumed. This clash essentially ended the era of massive, unregulated gatherings in the UK.

The Logistics of a Human Tidal Wave

Imagine the plumbing. Or rather, don't. The infrastructure of the Isle of Wight was never designed for an influx of half a million people. Ferries were backed up for days. Water ran low. Food became a secondary concern to finding a square foot of grass to sleep on.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Local residents were, understandably, terrified. Imagine waking up to find the population of a major city has parked themselves in your backyard, many of them naked, most of them high, and all of them looking for a toilet. This led directly to the "Isle of Wight Act 1971," a piece of legislation that strictly prohibited any gathering of more than 5,000 people on the island without a special license. They literally outlawed the festival after the fact.

- The Sound: Charlie Watkins of WEM provided the sound system. It was 1,500 watts. In 2026, your home theater might approach that, but for 1970, it was a monolith of power.

- The Cost: Tickets were roughly £3 for the whole weekend. Adjusting for inflation, that's about £50-£60 today. A steal, if you could actually get in.

- The Food: Described by many as "mush." Most people survived on bread, cheese, and whatever the "Hare Krishna" tent was handing out.

Miles Davis and the Jazz-Rock Collision

One of the most overlooked moments of the Isle of Wight 1970 was Miles Davis’s set. He showed up in a flamboyant leather outfit, looking like he’d stepped off a spaceship, and played a blistering 38-minute set of what would become "Bitches Brew" style fusion.

The rock crowd didn't quite know what to do with him. It wasn't "three chords and the truth." It was dense, dark, and challenging. But it proved that the festival wasn't just a pop event; it was a cultural crossroads. Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea were in that band. Think about that. Two of the greatest pianists in history, playing electric organs in a field in front of a bunch of kids on acid. It was weird. It was brilliant.

The Myth vs. The Reality

People like to romanticize these things. They look back and see a utopian gathering. But if you talk to the people who were actually there—the ones in the mud—it was a grit-your-teeth kind of experience.

💡 You might also like: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

It was windy. The site at Afton Down was exposed to the English Channel. It got cold at night. There were bad trips and medical emergencies. The "Desolation Row" vibes were real. Yet, despite the chaos, there was a sense of shared history. You were at the "British Woodstock," and you knew it was the last of its kind. When Leonard Cohen took the stage at 4:00 AM on the final night, he managed to calm the rioting crowd just by being his somber, poetic self. He told a story about a man in a circus and asked everyone to light a match. Suddenly, the violence stopped. The hill glowed. It was a brief moment of the "peace" everyone had been searching for.

Why We Are Still Talking About It

We talk about the 1970 festival because it represents the peak of a specific type of ambition. It was the moment the music industry realized it had outgrown its own shoes. The sheer logistics of 600,000 people proved that you couldn't just throw a party in a field anymore; you needed security, sanitation, and serious corporate backing.

It also served as a swan song for the 60s icons. Hendrix would be gone in September. Janis Joplin (who wasn't there but was part of that orbit) would follow shortly after. The Doors were nearing their end with Jim Morrison. The Isle of Wight 1970 was the funeral for an era that thought it could change the world with a guitar and a "free" ticket.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re interested in the legacy of the 1970 festival, you can still experience bits of it today, though the "vibe" has shifted significantly.

- Visit Afton Down: You can hike the area where the festival took place. There is a small, modest monument to the 1970 event featuring a bronze bust of Jimi Hendrix. It’s located near the Dimbola Lodge in Freshwater.

- Explore the Dimbola Museum: This was the home of Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, but it now houses a permanent exhibition dedicated to the 1970 festival. They have original posters, photographs, and artifacts that give you a sense of the scale without the mud.

- Check Out the Modern Festival: The Isle of Wight Festival was revived in 2002. It’s held at Seaclose Park now, not Afton Down. It is much more organized, far more expensive, and definitely has better toilets. But the spirit of bringing massive acts to a small island remains.

- Listen to the Raw Tapes: Don't just stick to the "best of" albums. Find the raw recordings of Leonard Cohen or The Who’s full set. The background noise—the wind, the heckling, the distance—gives you a better "you are there" feel than the polished studio remasters.

The 1970 festival wasn't perfect. It was a beautiful, chaotic, dangerous mess. But in a world where every festival now feels like a curated Instagram backdrop, there’s something deeply authentic about 600,000 people tearing down a fence just to hear a guitar scream into the night.