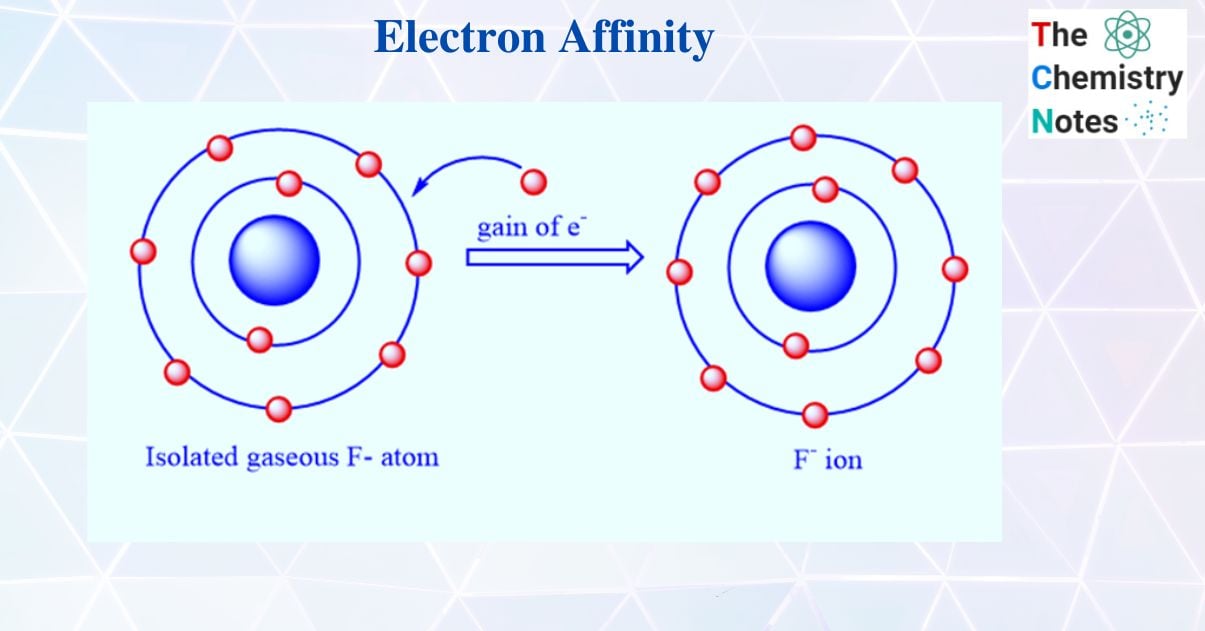

Ever wonder why some atoms are basically chemical hoarders while others couldn't care less? That's the heart of the matter. If you’ve ever cracked open a chemistry textbook, you’ve probably seen the term electron affinity tossed around alongside electronegativity or ionization energy. People mix them up constantly. It's annoying. But if we’re going to define the electron affinity correctly, we have to look at it as a measure of "greed" at the atomic level. Specifically, it is the energy change—usually a release—that happens when a neutral atom in the gas phase grabs an electron to become a negative ion.

Think of it like a transaction. The atom wants an electron. It gets one. In exchange, it spits out some energy.

👉 See also: Is Verizon Down NYC? How to Tell if It’s Just You or a Massive Fiber Cut

The Energy Exchange Nobody Explains Simply

Most folks think energy always goes up when you add stuff. Not here. When an atom like Fluorine snags an electron, it’s actually becoming more stable. It’s moving to a lower energy state. Because of that, it releases energy into the surroundings. That’s why electron affinity values are almost always written as negative numbers in thermodynamic tables. If the value is $-328 \text{ kJ/mol}$, the atom is basically shouting, "I feel so much better now that I have this electron that I’m throwing away 328 units of heat!"

But here is where it gets weird. Not every atom wants to join the party. Noble gases like Neon or Argon? They have zero interest. Their shells are full. To force an electron onto a Neon atom, you actually have to shove it in there using external energy. In those cases, the electron affinity is positive. It’s an uphill battle.

Why the Gas Phase Matters

You’ll notice every formal definition insists on the "gaseous state." Why? Because liquids and solids are messy. In a solid, atoms are constantly bumping into their neighbors, sharing electrons, and feeling the pull of a billion other nuclei. To get a "clean" reading of how much an atom truly wants an electron, you have to isolate it. You need it floating solo in a vacuum, far away from any distractions. That’s the only way to measure the pure, unadulterated attraction between a nucleus and a wandering electron.

Trends That Break the Rules

If you look at the periodic table, there’s a general vibe that electron affinity increases (becomes more negative) as you move left to right. This makes sense. As you move toward the Halogens, the nuclei get "stronger" because they have more protons pulling on the same electron shells.

But chemistry loves to lie to you. Or at least, it loves exceptions.

Take Nitrogen. You’d expect it to have a higher electron affinity than Carbon because it’s further to the right. Nope. Nitrogen has a half-filled p-subshell. That’s a very stable configuration. Adding one more electron creates electron-electron repulsion that Nitrogen just doesn't want to deal with. So, Nitrogen’s electron affinity is basically zero or even slightly positive. It’s the "leave me alone" of the periodic table.

Then there's the Chlorine vs. Fluorine debate. Fluorine is the most electronegative element, so you’d bet your house that it has the highest electron affinity. You’d lose that house. Chlorine actually has a higher electron affinity than Fluorine. Why? Fluorine is tiny. It’s so small that when you try to cram a new electron into its crowded valence shell, the existing electrons start kicking and screaming. The repulsion offsets some of the energy gained from the nucleus's pull. Chlorine is bigger, has more "elbow room," and welcomes the electron more gracefully.

First vs. Second Electron Affinity

This is a nuance that catches students off guard. The first electron affinity is usually exothermic (releases energy). But the second electron affinity? That’s always endothermic.

👉 See also: Area 51 Satellite Photos: What You Can Actually See From Space Right Now

Imagine you’re trying to push a negative electron toward a neutral atom. Easy. Now, imagine trying to push a negative electron toward an atom that is already negative. They repel each other like two magnets with the same poles facing. You have to use serious force to make that happen. This is why forming an $O^{2-}$ ion actually requires an input of energy, even though the resulting Oxide ion is stable in many crystal lattices.

Real-World Consequences of Atomic Greed

Why do we even care about this? Because it dictates the entire world of ionic bonding. When you define the electron affinity of an element, you’re predicting how it will behave in a battery, a solar cell, or a biological system.

- Semiconductors: In the tech world, we "dope" silicon with elements that have specific electron affinities to control the flow of current.

- Photography: Traditional film relies on the electron affinity of silver halides.

- Atmospheric Chemistry: The way pollutants react in the upper atmosphere often comes down to which molecule has the "stickier" grip on stray electrons.

How to Calculate and Compare

Scientists use the Born-Haber cycle to figure these numbers out. You can't just stick a thermometer into an atom. Instead, you measure other things—like the energy it takes to break a solid apart or the energy released when a salt forms—and work backward. It’s like figuring out the price of a burger by looking at the total receipt and subtracting the cost of the fries and the soda.

$E_{ea} = E_{\text{neutral}} - E_{\text{anion}}$

📖 Related: The Nimitz-class Nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carrier: Why It Still Rules the Waves After 50 Years

If the result of that equation is positive, energy was released. If it's negative, energy was absorbed. (Warning: some textbooks flip the sign convention just to be difficult, so always check if they are defining it as "energy added" or "energy released").

Actionable Steps for Mastering Atomic Trends

If you're trying to apply this knowledge, don't just memorize the table. Do this instead:

- Check the Subshells: Always look for half-filled or fully-filled subshells (Groups 2, 15, and 18). These are the spots where the "normal" trends break down because of stability.

- Size Matters: Remember the Fluorine/Chlorine flip. Smaller isn't always better if the electron cloud gets too crowded.

- Distinguish Terms: Stop using electronegativity and electron affinity interchangeably. Electronegativity is about sharing in a bond; electron affinity is about taking for yourself. One is a social skill; the other is a solo heist.

- Focus on the Anion: When you're looking at a reaction, ask: "How much does this atom want to be negative?" If the answer is "a lot," you're looking at a high electron affinity and a very stable product.

Understanding these energy shifts is the difference between guessing what a chemical will do and actually knowing why it happens. The universe isn't random; it's just trying to find the lowest energy state possible, one electron at a time.