Ever stared at a calendar in late February and felt like the universe was playing a prank on you? You’re looking for that extra square. It's there, then it's not. Most people know that every four years, we get a "bonus" day to fix our schedules, but the question of what month is a leap year really boils down to one specific, slightly awkward block of time: February.

February 29th. That’s the culprit.

It’s the shortest month of the year, yet it’s the only one that periodically stretches its legs. Why? Why not June? A leap day in June would mean an extra day of summer, more sunlight, and maybe a Tuesday that feels like a Saturday. Instead, the Romans—who basically invented this mess—decided to tack it onto the end of the winter. It was a "housekeeping" move that stuck for two millennia.

The Math Behind February 29th

The Earth doesn’t actually take 365 days to circle the sun. That’s a lie we tell ourselves for the sake of clean planners. It actually takes about 365.24219 days. If we ignored that extra quarter of a day, our seasons would eventually drift. Fast forward 700 years, and you’d be celebrating Christmas in the blistering heat of July.

📖 Related: Que Todo lo Bonito Llegue para Quedarse: Why We Struggle to Let the Good Times Last

Basically, we add a day to February to keep the vernal equinox—the first day of spring—around March 20th.

But wait. It’s not just "every four years." That’s a common misconception. If we added a day every four years without fail, we’d actually overcorrect. We’d be adding too much time. To fix that fix, the Gregorian calendar (the one you’re likely using right now) has a specific set of rules. A year is a leap year if it’s divisible by 4, unless it’s divisible by 100. But—and here’s the kicker—if it’s divisible by 400, it is a leap year again.

This is why the year 2000 was a leap year, but 1900 wasn't and 2100 won't be. It’s complicated. It’s messy. It’s the result of centuries of astronomers like Christopher Clavius trying to make sure Easter happened at the "right" time according to the moon and the sun.

Why February? Blame the Romans

If you’re wondering what month is a leap year and why it had to be the coldest, drabbest month for many of us, you have to look back at ancient Rome. Originally, the Roman calendar only had ten months. They didn't even bother naming the winter months; they just called it "winter" and waited for March to start the new year.

Eventually, King Numa Pompilius added January and February to the end of the year.

February was the last month. It was the "junk drawer" of the calendar. It was also the month of purification (februa). When Julius Caesar and his astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria realized the calendar was drifting away from the stars, they decided to add an extra day every few years. Since February was already the "leftover" month at the end of the year, it was the logical place to shove the extra day.

Even though we later moved the start of the year to January, February kept its reputation as the flexible month.

The Leapling Experience

Imagine being born on February 29th. You’re a "Leapling." You only get a "real" birthday once every 1,460 days. There are about 5 million people worldwide who share this birthday. Legally, it’s a bit of a headache. In many places, if you’re born on the 29th, your "legal" birthday on non-leap years is March 1st. In others, it’s February 28th.

The Honor Society of Leap Year Day Babies is a real thing. They’ve spent years documenting the weirdness of having a birthday that technically doesn't exist 75% of the time. Think about insurance forms. Think about automated drop-down menus on websites.

Honestly, it’s a glitch in the human system.

Does it actually matter?

Yes. If we stopped acknowledging the leap year month, the world would slowly fall out of sync. Farmers rely on the calendar for planting cycles. If the calendar drifts, the "last frost" date moves. Religious holidays tied to seasons, like Passover or Easter, would migrate across the seasons.

It’s about stability.

Not Everyone Uses the Same Month

While the Gregorian calendar is the global standard for business and tech, other cultures handle the "leap" differently. The Hebrew calendar, for instance, doesn't just add a day. It adds an entire leap month. This happens seven times within a 19-year cycle. This extra month, Adar I, is inserted before the "real" month of Adar (Adar II) to ensure that Passover always stays in the spring.

The Iranian (Persian) calendar is even more precise. It uses a 33-year cycle and relies on astronomical observations rather than a fixed rule. It’s arguably more "accurate" than our system, but it’s harder to program into a smartphone.

How to spot a leap year

You can usually tell if the year you're in is a leap year by looking at the summer Olympics or a U.S. presidential election. They almost always align with leap years. 2024 was a leap year. 2028 will be one. 2032 too. It's a rhythm we’ve built our society around.

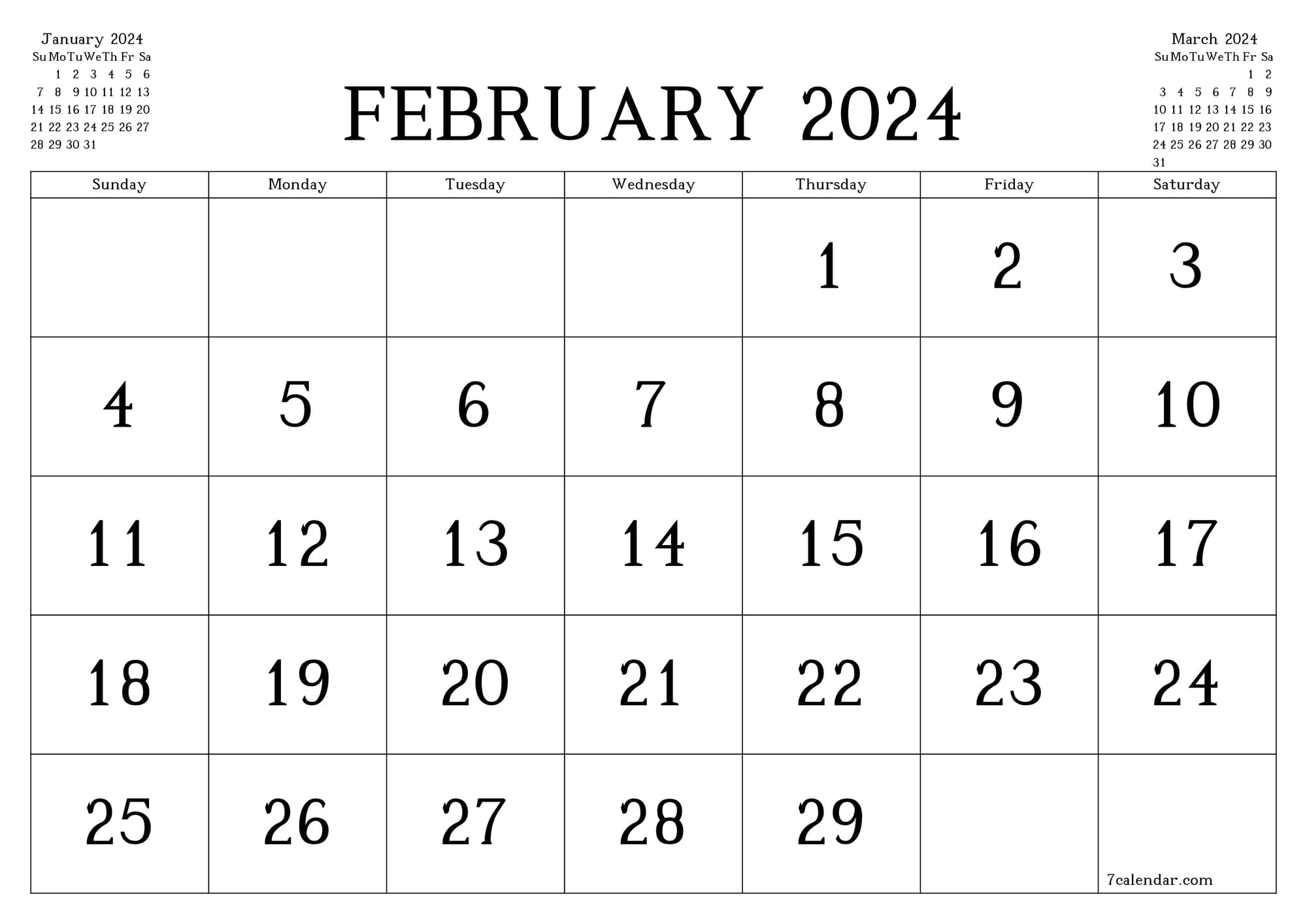

If you're ever in doubt about what month is a leap year, just check the February page. If it ends at 28, you're in a common year. If it hits 29, you've found the "intercalary" day.

Managing the Extra Day

What do you do with an extra 24 hours? In some traditions, February 29th is "Bachelor’s Day" or "Ladies' Privilege," a day when women were traditionally "allowed" to propose to men. This supposedly started in 5th-century Ireland with St. Bridget and St. Patrick. Whether that’s true or just a fun bit of folklore, it highlights how we treat the leap month as a "time out of time"—a day where the normal rules don't quite apply.

In modern times, most of us just work an extra day for the same salary if we're on a fixed monthly or annual pay. Technically, you’re working for free on February 29th if you’re a salaried employee. Sorta makes you want to rethink the whole system, doesn't it?

Actionable Takeaways for the Next Leap Year

Since the next leap year is approaching, you might want to prepare for the weirdness that February 29th brings.

- Check your expiration dates: If you have a subscription or a document that expires "at the end of February," make sure you know if that means the 28th or the 29th.

- Celebrate the "Leaplings": If you know someone born on this day, make a big deal out of it. They only get four "real" birthdays in 16 years.

- Audit your software: If you’re a developer or a business owner, ensure your systems recognize February 29th. "Leap year bugs" are a real thing and can crash legacy systems that assume February always has 28 days.

- Take the "Leap Day" off: If your schedule allows, use that extra day to do something you normally wouldn't have time for. It’s a gift of 1,440 minutes that wouldn't exist otherwise.

The leap year month is a quirky, necessary patch on the fabric of time. Without it, our world would eventually lose its connection to the stars and the seasons. So, the next time February rolls around with an extra day, don't just ignore it. Acknowledge the weird Roman history and the complex math keeping our lives on track.

Next Steps to Stay On Track:

- Sync your digital calendars: Most modern apps handle leap years automatically, but it's worth checking any manual spreadsheet trackers you use for long-term planning.

- Verify legal documents: If you are a Leapling or have a child born on Feb 29, confirm the legal "effective birthday" in your specific state or country for things like driver's licenses or social security.

- Plan for 2028: Mark your calendar now for the next leap day. Use it as a quadrennial "reset" for long-term goals that require more than a year to achieve.