Ever stood outside in a January blizzard and felt like your eyelashes were actually turning into needles? It’s brutal. You start wondering just how low the mercury can go before the universe basically decides to give up. We’ve all seen the news reports about record-breaking winters in Oymyakon, Russia, where the air hits -67°C and your breath turns into "the whisper of stars" as ice crystals fall to the ground. But when we ask what is the coldest, we aren't just talking about a bad day in Siberia. We are talking about the physical limits of reality itself.

It’s bone-chilling.

Most of us learned in high school that the ultimate floor is Absolute Zero. That’s $0$ Kelvin, or $-273.15$°C. At this point, theoretically, all molecular motion stops. No jiggling. No heat. Just... nothing. But if you talk to a physicist at MIT or the University of Colorado Boulder today, they’ll tell you that "cold" gets a lot weirder than a simple number on a thermometer.

The coldest places in the known universe (and they aren't in space)

You might think the Boomerang Nebula, which sits about 5,000 light-years away, holds the crown. It’s a dying star gushing out gas so fast that it cools down to about $1$ Kelvin. That’s colder than the background radiation of the Big Bang. It’s a natural refrigerator in the middle of a vacuum.

However, humanity has actually beaten nature at its own game.

The coldest place we know of is right here on Earth. Specifically, in labs like the Cold Atom Lab (CAL) on the International Space Station or the various dilution refrigerators in research universities. In these controlled environments, scientists use lasers—which sounds counterintuitive because lasers usually burn things—to pelt atoms and force them to slow down. By doing this, they’ve reached temperatures as low as a few hundred pikoKelvin. That is less than a billionth of a degree above absolute zero.

✨ Don't miss: Why Sony Over Ear Wired Headphones Still Win (Even With Bluetooth Everywhere)

Why do we do this? It’s not just for bragging rights. When things get that cold, the rules of the world we see every day just stop working. Atoms start overlapping. They lose their individual identities and form what’s called a Bose-Einstein Condensate (BEC). It’s essentially a "super-atom" where everything moves in perfect unison.

Can we ever actually reach absolute zero?

The short answer is no. Honestly, it's impossible.

This is thanks to the Third Law of Thermodynamics. You can get infinitely close, but you can’t quite cross the finish line. Think of it like trying to reach a wall by only ever moving half the remaining distance. You’ll get closer and closer, but you’ll never actually touch the brick. In the quantum world, there is also something called "zero-point energy." Even at the absolute lowest energy state, quantum mechanics says there has to be some residual "jitter."

The universe has a basement, but we can't quite step onto the floor.

The weirdness of "Negative Temperatures"

Now, this is where it gets kinda trippy. In 2013, researchers at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich published a paper in Science that flipped the script. They created a gas that technically had a negative Kelvin temperature.

Wait. What?

If absolute zero is the bottom, how can you go lower? It’s not actually "colder" in the way we think about it. Temperature is basically a measure of how energy is distributed among particles. In a normal system, most particles have low energy and a few have high energy. If you flip that—where most particles are at the high-energy state and very few are at the low-energy state—the math for temperature actually results in a negative number.

📖 Related: Signs of AI Generated Images: Why You Are Probably Getting Fooled

These "negative temperature" systems are actually incredibly hot in terms of energy, but they behave in ways that mimic the coldest systems imaginable. They could eventually help us build engines that are more than 100% efficient, which sounds like sci-fi but is a legitimate area of study in quantum thermodynamics.

Understanding the "Coldest" in Everyday Life

While scientists are playing with pikoKelvins, the rest of us are just trying to keep our pipes from bursting. It's helpful to look at the scale of what is the coldest to see where we fit:

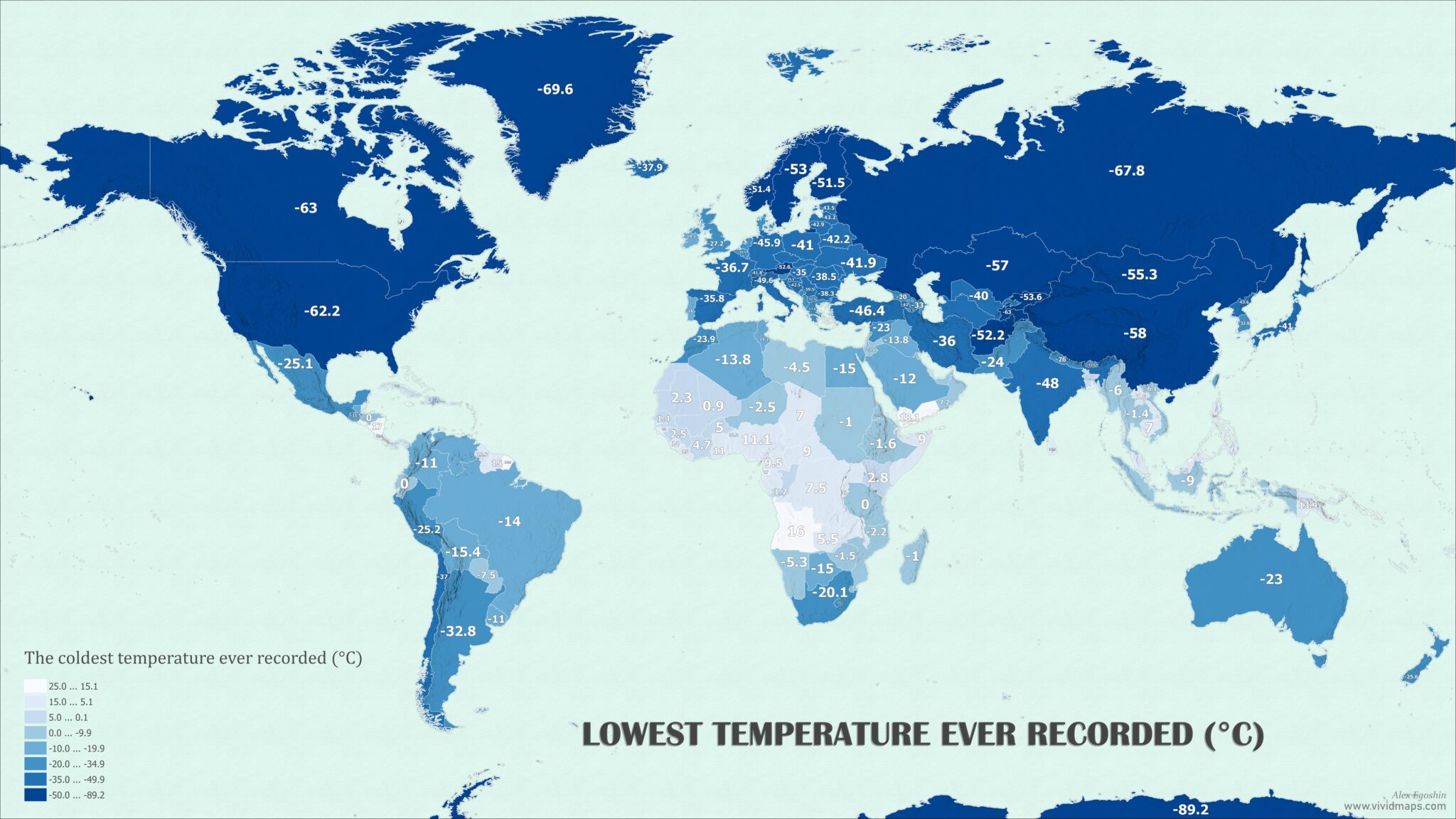

- -89.2°C: The coldest temperature ever recorded on the surface of the Earth (Vostok Station, Antarctica, 1983).

- -196°C: Liquid nitrogen. This is what you use to freeze off warts or make really fancy ice cream.

- -269°C: Liquid helium. This is used to cool the superconducting magnets in MRI machines at your local hospital.

- -273.15°C: The theoretical limit of absolute zero.

If you’re wondering why your car won't start at -20°C, remember that the atoms in your engine block are still vibrating with an incredible amount of energy compared to what's happening in a lab.

The practical reality of extreme cold

We tend to think of cold as a "thing," like a blanket of frost. But cold is just the absence of heat. It’s the absence of motion.

In the tech world, mastering the "coldest" environments is the only way we are going to get functional quantum computers. These machines rely on qubits, which are notoriously finicky. If a qubit gets even a tiny bit of heat—just a stray vibration from a passing truck outside—it loses its "entanglement" and the calculation fails. This is why companies like IBM and Google have these massive gold-plated "chandeliers" (dilution refrigerators) that keep their chips at roughly $0.015$ Kelvin.

That is colder than the vast majority of deep space.

How to explore the "Coldest" yourself

If you're fascinated by the limits of temperature, you don't need a PhD to see the effects. You can observe the transition of matter in simple ways, though maybe don't try to reach absolute zero in your kitchen.

- Look into Cryogenics: Understand that the leap from "refrigeration" to "cryogenics" usually happens around -150°C. This is the point where gases like oxygen and nitrogen turn into liquids.

- Study Superconductors: Look up videos of the Meissner Effect. When materials get cold enough, they expel magnetic fields and can levitate. It’s the closest thing to real magic you’ll ever see in a lab.

- Monitor the James Webb Space Telescope: This telescope has to stay incredibly cold to "see" infrared light from the early universe. Its mid-infrared instrument (MIRI) uses a "cryocooler" to stay below $7$ Kelvin. If it gets any warmer, its own heat would blind its sensors.

The quest for what is the coldest isn't just a race to the bottom of the thermometer. It is a journey into the heart of how matter is constructed. We are finding that at the very edge of stillness, the universe becomes more active and stranger than we ever imagined.

✨ Don't miss: k1c mcu fan upgrade: What Most People Get Wrong

To stay informed on these developments, keep an eye on the "Cold Atom Lab" updates from NASA. They are currently performing experiments in orbit that are impossible on Earth because gravity interferes with the way cold atoms move. By removing gravity from the equation, they can observe these "frozen" states for longer periods, potentially unlocking new states of matter that don't even have names yet.

The floor is lower than we thought, and we're still descending.