You’ve probably heard the word "algorithm" tossed around like some mystical incantation that decides what you buy, who you vote for, and which cat video ruins your productivity at 2 AM. In the world of software development, people treat it with this weird, hushed reverence. But if we’re being real, stripped of the Silicon Valley buzzwords, an algorithm in coding is just a recipe. That’s it. It’s a set of instructions.

Think about making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. If you tell a robot "make a sandwich," it’ll freeze. It doesn't know what a sandwich is. You have to break it down: Get bread. Open jar. Use knife. Spread. If you miss a step, or put the jelly on the outside of the bread, the "algorithm" failed. Coding is exactly that, just with more semicolons and fewer breadcrumbs.

Why Everyone Obsesses Over the Definition

Computers are incredibly fast, but they are also profoundly stupid. They don't have intuition. They don't "get the gist" of what you’re trying to do. This is why understanding an algorithm in coding is the bridge between human thought and machine execution. You are essentially translating "find the cheapest flight to Tokyo" into a series of logical comparisons that a processor can chew on.

Ada Lovelace, often cited as the first computer programmer, realized this back in the 1840s. She wrote an algorithm for Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers. She wasn't just "coding"—she was creating a logical path for a machine that didn't even fully exist yet. That’s the core of it. Logic first, syntax second.

The Ingredients of a Solid Algorithm

Not every piece of code is an algorithm, but every algorithm needs code to run. To qualify as an actual algorithm, most computer scientists—like those following the classic definitions laid out by Donald Knuth in The Art of Computer Programming—look for a few specific traits.

First, it has to be finite. If your code runs forever in a loop without stopping, it’s not an algorithm; it’s a bug (or a very expensive way to heat your room). It also needs to be unambiguous. Every step must be crystal clear. "Add a little bit of salt" works for a chef, but for a coder, it has to be salt += 0.05.

Inputs and outputs are the bookends. You give the algorithm something (like a list of names), and it gives you something back (like those names in alphabetical order). If nothing comes out, you’ve basically just written a digital black hole.

Sorting and Searching: The Bread and Butter

Most of what you interact with online boils down to two things: finding stuff and putting stuff in order.

Take "Bubble Sort." It’s the algorithm everyone learns first in CS101, and honestly? It’s kind of terrible. It works by looking at two items, swapping them if they’re in the wrong order, and repeating that until the list is sorted. It’s slow. It’s clunky. But it’s an algorithm.

On the flip side, you have "Quicksort." It’s much faster because it uses a "divide and conquer" strategy. It picks a "pivot" element and shuffles everything else around it. This distinction matters because in the real world, efficiency is money. If Amazon’s search bar used a slow algorithm to sort products, you’d be staring at a loading spinner until you decided to go to the mall instead.

The Big O: How We Measure "Good"

We don't just say an algorithm is "fast" or "slow." We use something called Big O Notation. It sounds intimidating, but it’s just a way to describe how the execution time grows as you add more data.

$O(1)$ is the dream. It means no matter how much data you have, the task takes the same amount of time. $O(n)$ means if you double the data, you double the time. Then you have $O(n^2)$, which is where things get scary. If you have 10 items, it’s 100 operations. If you have 1,000 items, it’s a million. This is why choosing the right algorithm in coding isn't just a nerd debate—it’s the difference between an app that feels snappy and one that crashes your phone.

Algorithms Are Not Just for Math Nerds

You use algorithms every time you interact with technology, even if you don't see the code.

- Pathfinding: When Google Maps finds the quickest route to the airport while avoiding that one construction zone on 5th Street, it’s likely using Dijkstra’s Algorithm or A*. It calculates the "cost" of every road segment and finds the path with the lowest total.

- Compression: How do you fit a high-definition movie into a tiny file? Algorithms like Huffman Coding look for patterns in data and shrink them down without losing the important bits.

- Cryptography: Every time you buy something online, RSA or AES algorithms are scrambling your credit card info so hackers can't read it. It’s all just complex math applied through code.

The "Bias" Problem Nobody Likes to Talk About

Here is the thing: algorithms are often viewed as objective. We assume that because a computer did the math, the result is "fair." But algorithms are written by people. And people have biases.

If a hiring algorithm is trained on resumes from the last twenty years, and for the last twenty years the company mostly hired people named "Dave," the algorithm might start "thinking" that being named Dave is a requirement for the job. This isn't science fiction. Real-world systems in healthcare, policing, and banking have faced massive scrutiny for "algorithmic bias."

It’s a reminder that an algorithm in coding is only as good as the data it’s fed and the logic the programmer provides. We can't just outsource our ethics to a .py file and hope for the best.

Machine Learning: When Algorithms Write Algorithms

This is where it gets meta. In traditional coding, the human provides the rules. In Machine Learning (ML), the human provides the data, and the computer figures out the rules itself.

💡 You might also like: Dyson Cyclone V10 Motorhead: Why This Older Model Still Beats Newer Vacuums

Think of a Neural Network. It’s an algorithm inspired by the human brain. You show it 10,000 pictures of a cat, and eventually, it figures out the patterns that define "cat-ness." It’s still an algorithm, but it’s one that evolves. This is how ChatGPT works, how Tesla’s Autopilot navigates, and how Netflix knows you’re probably going to binge-watch that baking show this weekend.

How to Start Thinking Like a Coder

If you want to get good at this, stop trying to memorize syntax. Seriously. Don't worry about where the brackets go yet. Instead, start looking at everyday problems as a series of steps.

How would you explain how to tie a shoe to someone who has never seen a string?

How would you sort a deck of cards by suit and rank using the fewest moves possible?

That’s algorithmic thinking. Once you can map out the logic on a whiteboard or a napkin, turning it into Python, Java, or C++ is just a translation job.

Actionable Next Steps for Mastering Algorithms

If you're ready to move past the theory and actually start building, here is how you should spend your next few hours:

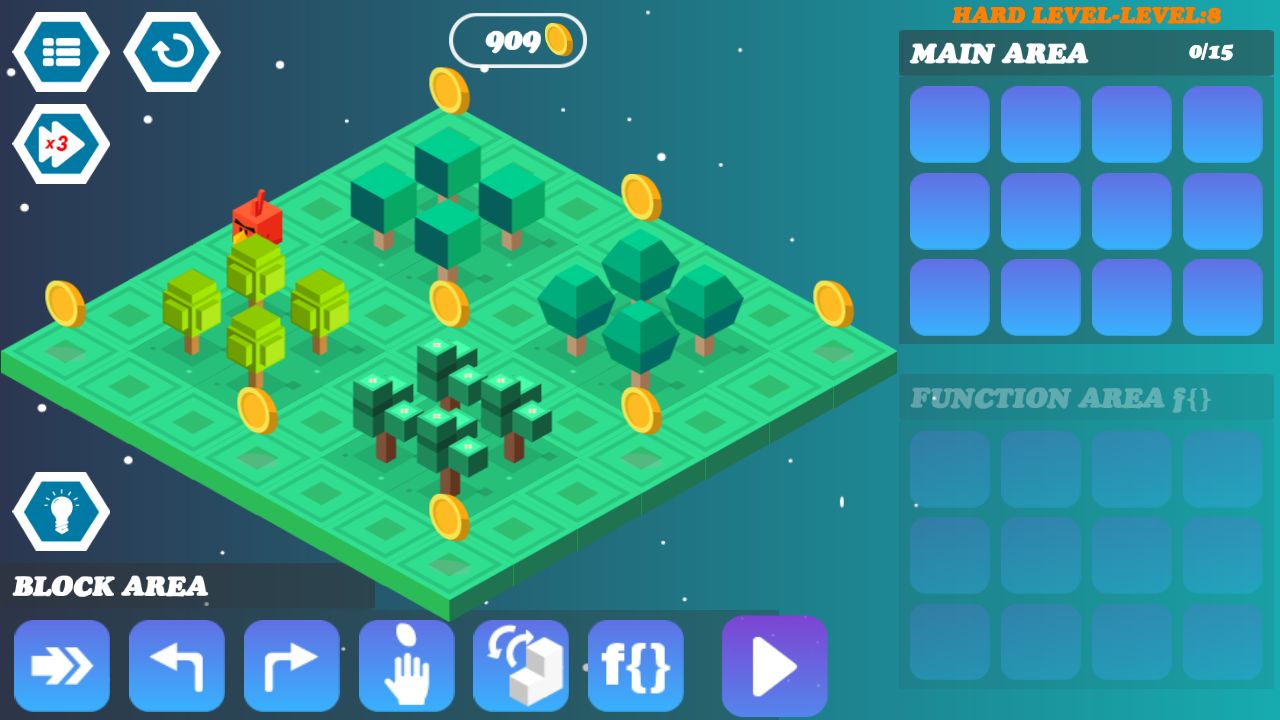

- Visualize the Logic: Use tools like VisuAlgo to see how sorting and searching actually look in motion. Seeing the bars move makes Big O notation click way faster than reading a textbook.

- The "Pen and Paper" Rule: Before you type a single line of code for a problem, write the steps out in "Pseudocode." If you can't explain it in plain English, you can't code it.

- Practice "Leetcoding" (But Don't Overdo It): Sites like LeetCode or HackerRank are great for practicing specific patterns, but don't let them burn you out. Focus on understanding why a Hash Table is faster than an Array for certain tasks.

- Build a "Useless" Project: Create a script that renames all the files in a folder based on their date, or an app that decides what you should eat for dinner based on a random number generator. Small, real-world applications are where the "recipe" of an algorithm becomes second nature.

Understanding an algorithm in coding is less about being a math genius and more about being a clear communicator. You’re telling a story to a machine. Make sure it's a story that actually makes sense.