You’ve been using them since you were a toddler. "Go," "eat," "sleep," "play." But if someone corners you at a party and asks, "Hey, what is a verb meaning, exactly?" you might stumble. Honestly, most of us just think of them as "doing words." That’s the definition your second-grade teacher probably gave you. It’s fine for an eight-year-old. It's not quite enough for anyone trying to master a second language or write a decent email.

Verbs are the heavy lifters of the English language. Without them, a sentence is just a pile of nouns sitting there, doing absolutely nothing. Imagine a world with just nouns. "Tree." "Cat." "Pizza." Pretty boring, right? You need the verb to give that pizza a purpose—to "bake" it, "slice" it, or "devour" it.

The Basic Definition (And Why It’s Incomplete)

Basically, a verb is a word that describes an action, an occurrence, or a state of being. But here’s where it gets kinda tricky. People get stuck on the "action" part. They think if there isn't someone running or jumping, there isn't a verb. That’s a mistake. Some of the most powerful verbs in our language are the quietest ones.

Take the word "is." It doesn't look like an action. Nobody "ises" around a track. Yet, "is" (a form of the verb "to be") is the most common verb in English. It describes a state of being. Without it, you can't even define who you are.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a verb as a word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence, forming the main part of the predicate of a sentence. That "predicate" part is linguist-speak for the part of the sentence that tells you something about the subject. If the subject is the "who," the verb is the "what’s happening."

Not All Actions Are Physical

We often split verbs into two camps: dynamic and stative. This is where most people get confused about the "what is a verb meaning" question.

Dynamic verbs are the easy ones. Kick. Shout. Melt. Explode. You can see these happening. You can take a photo of someone "kicking" a ball. These verbs describe things that have a beginning and an end, or at least a clear process.

Then you have stative verbs. These are the "invisible" verbs. They describe thoughts, emotions, relationships, and senses. Think about words like "love," "believe," "belong," or "weigh." You don't "do" the act of weighing in the same way you "do" a pushup. You just are a certain weight. If you tell someone "I love pizza," you aren't performing a specific physical movement at that exact moment. You're describing a state of your heart (or your stomach).

Linguists like Steven Pinker have written extensively about how our brains categorize these differently. In his book The Stuff of Thought, Pinker explores how verbs actually shape how we perceive reality. We view the world through these semantic lenses. Some languages don't even use verbs the same way we do, which changes how those speakers perceive time and causality.

The Tense Problem: Verbs and Time

Verbs are the only part of speech that carries the burden of time. Nouns don't change if they happened yesterday. A "dog" today was a "dog" in 1920. But a verb? It morphs. It bends.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

This is called conjugation. In English, we’re actually pretty lucky. Our conjugation is relatively simple compared to French or Spanish. But it still trips people up. You have the past, the present, and the future. Then you get into the weird stuff like the "present perfect" (I have eaten) or the "past progressive" (I was eating).

Why does this matter for the meaning of a verb? Because the meaning changes based on when it happens. "I run" is a general statement about your habits. "I am running" means you're probably out of breath right now. "I will run" is a promise you might break tomorrow morning.

Irregular Verbs: The Rebellious Children

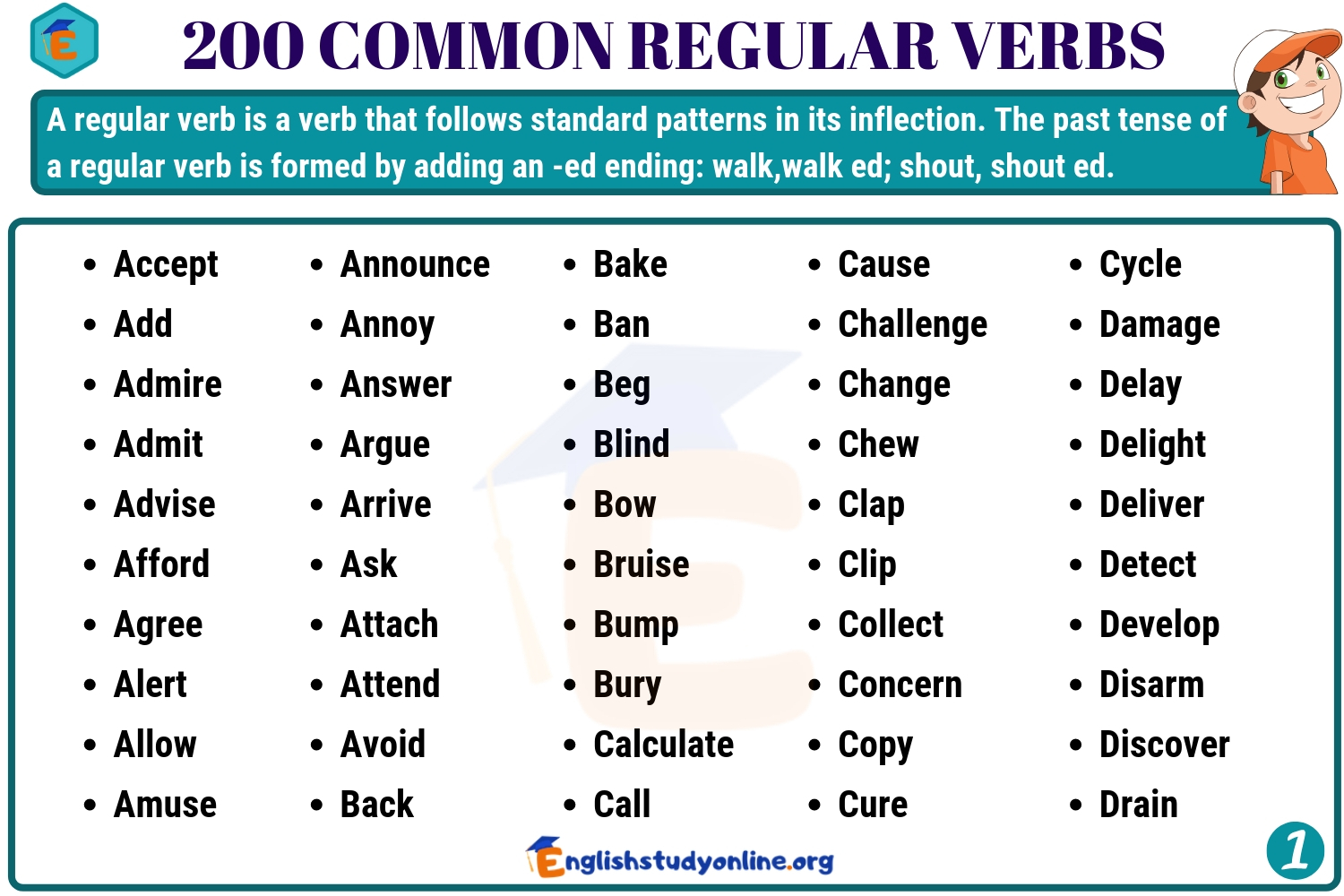

English is famous for its irregular verbs. Most verbs follow the "add -ed" rule for the past tense. Talk becomes talked. Walk becomes walked. Simple.

Then you have the rebels.

Go becomes went.

Buy becomes bought.

Sing becomes sang (but not sung, unless you’ve "have sung").

These exist because of the history of the English language—a messy blend of German, Old Norse, French, and Latin. These words are so common that they resisted the "leveling" of the language over centuries. We used them so much we refused to change them to fit the new rules.

Helping Verbs and Why They Aren't Cheating

Sometimes one verb isn't enough. You need a "helper." These are officially called auxiliary verbs.

Common helpers include:

- Can

- Could

- Shall

- Should

- Will

- Would

- May

- Might

- Must

These change the "mood" of the main verb. Compare "I eat the sandwich" to "I might eat the sandwich." That one little word changes the entire certainty of the sentence. It moves the meaning from a fact to a possibility.

There are also "modal" verbs that express necessity or permission. If your boss says "You must finish this," the verb meaning is tied to obligation. If they say "You can finish this," the meaning shifts to ability or permission. It’s subtle, but it’s the difference between keeping your job and having a relaxed afternoon.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

Transitive vs. Intransitive: The Hidden Logic

This is the stuff they usually skip in school because it sounds boring, but it’s actually the key to writing better sentences.

A transitive verb needs an object. It "transfers" its action to something else.

Example: "He kicked the ball."

If you just say "He kicked," people are going to ask, "Kicked what?" The meaning feels incomplete.

An intransitive verb stands alone.

Example: "She laughed."

You don't laugh a thing. You just laugh. The action is self-contained.

Some verbs can be both. "I eat" works fine on its own, but "I eat tacos" adds that specific object. Understanding this helps you spot why some sentences feel "off" even if the spelling is perfect.

The Ghost in the Machine: Phrasal Verbs

If you’re learning English as a second language, phrasal verbs are probably your nightmare. This is when a verb teams up with a preposition or adverb to create a completely new meaning.

Take the verb "run."

- Run out (to have none left)

- Run into (to meet someone by chance)

- Run over (to hit with a car)

- Run through (to practice)

The individual "what is a verb meaning" for "run" doesn't help you here. You have to learn the whole phrase as a single unit of meaning. It’s idiomatic. It’s weird. It’s very English.

How to Use Verbs to Level Up Your Writing

If you want to sound more authoritative or more engaging, stop relying on adverbs and start picking better verbs.

Instead of saying "He ran very quickly," try "He sprinted."

Instead of "She walked slowly and sadly," try "She trudged."

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Strong verbs carry their own descriptions. They don't need "very" or "really" to prop them up. When you use a precise verb, you give the reader a clearer mental image. This is the "Show, Don't Tell" rule in action.

Also, watch out for the "passive voice." This happens when the object of the action becomes the subject of the sentence.

Passive: "The cake was eaten by the dog."

Active: "The dog ate the cake."

The active version is almost always punchier. It puts the "doer" front and center. It makes the verb pop.

Common Misconceptions About Verbs

One big myth is that all verbs must be "active" to be good. That’s not true. Sometimes you need the "to be" verbs to establish a scene or a feeling. "The room was cold" is a perfectly fine sentence. You don't always need to say "The cold air bit at my skin," though sometimes that's better.

Another misconception is that infinitives (the "to" form of a verb, like "to go") should never be split. You've probably heard you shouldn't say "to boldly go." That’s actually an old rule based on Latin, where you literally couldn't split an infinitive because it was one single word. In English, it’s two words. Sometimes splitting them sounds more natural. Don't be afraid to break that rule if it makes your sentence flow better.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Verbs

You don't need to memorize a grammar textbook to get this right. Start with these three habits:

The "To Be" Audit: Go through a paragraph you wrote. Circle every time you used "is," "was," "were," or "are." See if you can replace half of them with more descriptive action verbs. It will instantly make your writing more "human" and less robotic.

Check Your Objects: When you use a verb, ask yourself if it needs an object. If you find yourself writing sentences that feel like they're hanging off a cliff, you might be using a transitive verb without a destination.

Listen for Phrasals: Pay attention to how people speak. Notice how often we use "give up" instead of "surrender" or "set up" instead of "arrange." Using phrasal verbs makes your writing sound conversational and relatable, while using the formal Latinate versions (surrender, arrange) makes you sound more academic.

Understanding the meaning of a verb isn't just about school drills. It’s about understanding how we move through the world. Every sentence you speak is an attempt to connect a subject to an action or a state. The better you choose your verbs, the more clearly that connection lands.

Start by looking at the last three things you did today. Don't just say you "did" them. Did you "tackle" them? Did you "slog" through them? Did you "breeze" past them? The verb you choose tells the real story.