You’re looking at the radar. There’s this giant, lazy "U" shape dipping down from Canada, carving its way across the Midwest and dragging a mess of gray clouds behind it. The meteorologist on the local news keeps pointing at these dashed lines and talking about "troughing." It sounds technical. It sounds like something you’d find in a farmyard for pigs to eat out of. But in the sky, it’s basically the engine room for bad weather.

So, what is a trough in weather?

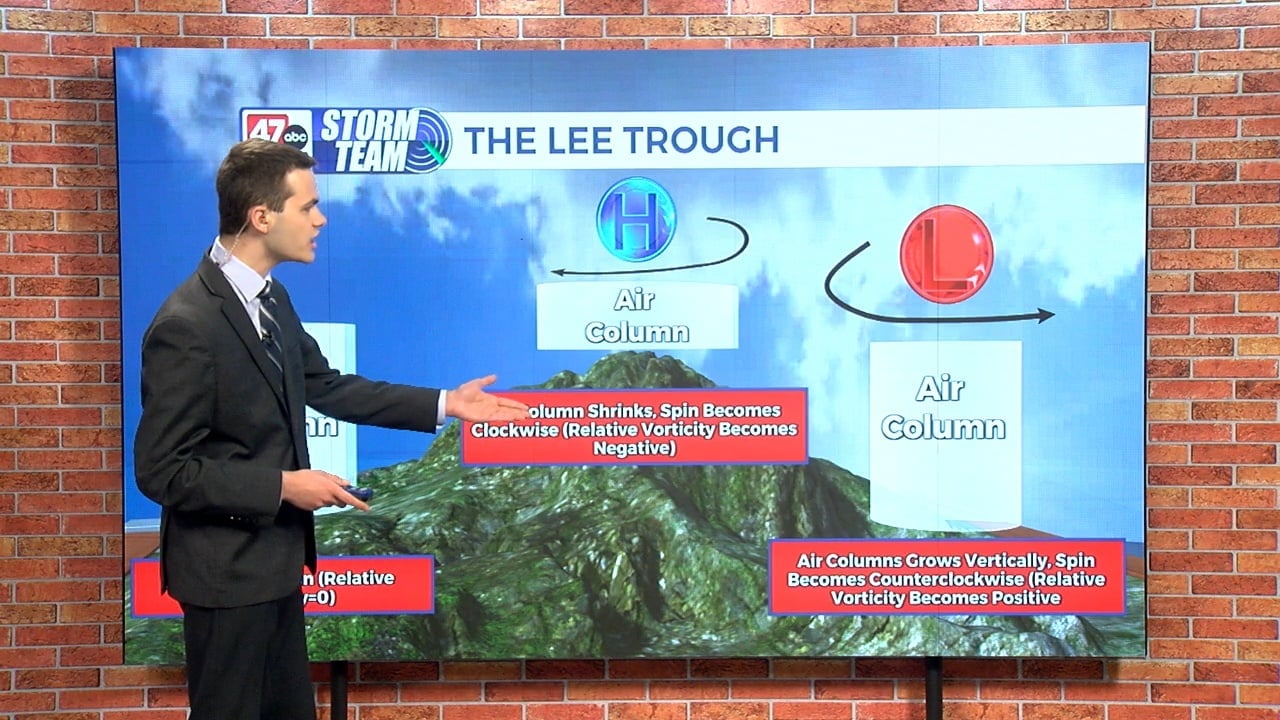

At its simplest, a trough is an elongated area of relatively low atmospheric pressure. Think of the atmosphere like a giant, invisible ocean of air. If a high-pressure system is a mountain of air pushing down on us, a trough is a valley. It’s a literal dip in the pressure field. Because nature hates a vacuum and loves to move things around, that valley becomes a magnet for wind, moisture, and generally miserable conditions.

It’s not a closed circle like a cyclone or a hurricane. Instead, it’s open. It’s a wave. And like a wave in the ocean, it moves, carrying energy with it.

The Anatomy of the Dip

To understand a trough, you have to look at the jet stream. This is that high-altitude river of air that screams across the planet from west to east. It rarely flows in a straight line. It meanders. When the jet stream dips south, it creates a "trough." When it bulges north, you get a "ridge."

Ridges bring the heat and the blue skies. Troughs bring the drama.

💡 You might also like: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

Inside that trough, air is being forced to rise. This is the golden rule of meteorology: rising air cools, moisture condenses, and you get clouds. If the trough is deep enough—meaning the pressure is significantly lower than the air around it—you’re looking at rain, snow, or even severe thunderstorms. Meteorologists like Jeff Haby often point out that the most "active" part of a trough is usually on its eastern side. That's where the air is being unceremoniously shoved upward by the approaching wave of cold, dense air.

Why Troughs are Basically Weather Factories

You’ve probably noticed that a "cold front" is usually what gets the blame for a rainy Tuesday. But a cold front is often just the leading edge of a trough.

Imagine a trough as a giant snowplow.

As it moves, it forces the warm, moist air ahead of it to get out of the way. Since that warm air can’t go into the ground, it goes up. This creates a line of lifting that fuels everything from a light drizzle to those massive "supercell" storms that haunt the Great Plains in May.

There are different "flavors" of troughs, too. You might hear someone mention a shortwave trough. These are smaller, faster-moving ripples embedded within the larger flow. They’re the "surprises" of the weather world. A major trough might sit over the Eastern U.S. for a week, giving you generally gloomy weather, but a shortwave trough rippling through that flow is what actually triggers the specific burst of heavy snow or the sudden afternoon thunderstorm.

📖 Related: Clayton County News: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gateway to the World

Then there’s the inverted trough. Usually, troughs point south in the Northern Hemisphere. But sometimes, especially in the tropics or near the Gulf of Mexico, they point north. These are notorious for being "rain machines" that don't always show up well on standard surface maps, catching people off guard with three days of relentless downpours.

The Real-World Impact: More Than Just Rain

In 2021, a massive "meridional" flow—which is just a fancy way of saying the jet stream was making huge, deep troughs and ridges—led to some of the most lopsided weather in history. While a ridge "baked" the Pacific Northwest in a deadly heatwave, a deep trough settled over the central U.S., bringing unseasonably cool air and floods.

Troughs also dictate where hurricanes go.

If a hurricane is chugging along in the Atlantic and a big trough moves off the East Coast of the U.S., the trough acts like a vacuum. It pulls the hurricane toward it and then "slingshots" it back out to sea or up the coast. Forecasters at the National Hurricane Center spend half their lives staring at troughs in the mid-latitudes because those troughs are the steering wheels for the biggest storms on Earth.

Recognizing a Trough Without a Degree

You don't need a PhD to spot one.

👉 See also: Charlie Kirk Shooting Investigation: What Really Happened at UVU

If the wind has been blowing from the south or southwest for a day—bringing in humidity—and then it suddenly shifts to the west or northwest as the clouds roll in, a trough axis has likely just passed over you. The "axis" is the very bottom of that "U" shape. Once the axis passes, the pressure starts to rise, the air dries out, and the "backside" of the trough brings in the cooler, clearer air.

It’s a cycle. Ridge, trough, ridge, trough.

The atmosphere is constantly trying to balance itself out. It takes the hot air from the equator and tries to shove it north, while the cold air from the poles tries to dump south. The trough is the vehicle for that cold air.

What to Do When a Trough is Inbound

When you hear the term "trough" in a forecast, stop thinking about a single storm and start thinking about a "pattern shift."

- Check the "Tilt": If a meteorologist says a trough is "negatively tilted" (leaning from the southeast to the northwest), pay attention. These are the ones that produce the most violent weather and tornadoes because they allow for maximum "exhaust" of air at high altitudes.

- Watch the Barometer: If you have a weather station at home, watch the needle. A steady drop over 12 to 24 hours almost always signals a trough approaching.

- Plan for Lingering Clouds: Unlike a sharp cold front that might pass in two hours, a broad trough can keep things "soupy" for days. If the trough is "cutoff"—meaning it gets separated from the main jet stream—it can park itself over your house and refuse to move until it literally spins itself out of existence.

Understanding the trough is about understanding the "why" behind the rain. It’s the structural valley in our sky that dictates whether you’re having a BBQ or huddling in the basement. Next time you see those dashed lines on a weather map, you'll know exactly why the atmosphere is about to get restless.

Practical Steps for Weather Readiness

- Monitor the 500mb Map: This is where the pros look for troughs. Most weather apps show surface data, but sites like Tropical Tidbits or the National Weather Service show the "upper-air" maps where troughs are most visible.

- Look for the Wind Shift: If you’re outdoors, watch the clouds. If the high-level clouds are moving in a different direction than the wind at the surface, a trough is likely nearby, creating "shear," which is a prime ingredient for stormy weather.

- Timing the Axis: Use satellite imagery to find the back edge of the cloud shield. That back edge usually marks the passage of the trough axis and the beginning of improving weather.