You think you know what temperature is. It’s hot, it’s cold, it’s the number on your iPhone that tells you whether to grab a parka or a t-shirt. But if you ask a physicist what does temperature mean, they aren’t going to talk about "warmth." They’re going to talk about chaos.

Everything around you is vibrating. The chair you’re sitting in, the coffee in your mug, even your own skin—it’s all a frantic mess of molecules slamming into each other like a never-ending mosh pit. Temperature is just a way to measure the average speed of that microscopic madness.

It’s kinetic energy. That’s it.

When you heat up a pot of water, you aren't just "adding heat." You are physically whipping those water molecules into a frenzy. They move faster. They bounce harder. Eventually, they’re moving so fast they break free from their liquid bonds and go flying off into the air as steam. On the flip side, when things get cold, that movement slows down. If you could get something cold enough—specifically -273.15°C—everything would theoretically stop moving entirely. That’s Absolute Zero. No vibrations. No jiggling. Just total, eerie stillness.

The Messy Reality of Kinetic Energy

We have this habit of conflating "heat" and "temperature," but they are totally different animals. Think of it like this: Temperature is the intensity of the party, while heat is the total energy in the room.

Imagine a single spark flying off a campfire. That spark is at a massive temperature—maybe $1,500$ degrees. If it lands on your arm, it stings, but it doesn't kill you. Now imagine a bathtub full of lukewarm water. The temperature is low, maybe only $100$ degrees, but there is way more "heat" in that tub because there are trillions more molecules carrying energy.

This is why the "feel" of temperature is so deceptive.

Have you ever stepped onto a tile floor in the morning? It feels freezing. Then you step onto a rug right next to it, and it feels fine. Here’s the kicker: they are the exact same temperature. Your feet aren't measuring temperature; they’re measuring the rate of energy transfer. The tile is a conductor—it’s a greedy thief stealing the heat from your skin as fast as it can. The rug is an insulator, so it lets you keep your warmth.

When people ask what does temperature mean in a practical sense, they’re usually asking about how energy moves from Point A to Point B. We are essentially walking thermal sensors that are remarkably bad at being objective.

Lord Kelvin and the Quest for a True Zero

In the mid-1800s, William Thomson—later known as Lord Kelvin—realized that the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales were a bit arbitrary. They were based on the freezing points of water or, in Fahrenheit's weird case, a specific mixture of ice, water, and ammonium chloride.

Kelvin wanted something absolute.

He understood that if temperature is just molecular motion, there has to be a floor. You can’t go slower than "stopped." This led to the Kelvin scale, which is the gold standard in science today. In the world of Kelvin, there are no negative numbers. You’re either moving, or you aren't.

- 0 K: Absolute Zero. The motion stops.

- 273.15 K: Water freezes (0°C).

- 373.15 K: Water boils (100°C).

Physicists like those at CERN or the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) use these absolute measurements because they don't care about how "hot" something feels; they care about how much work those molecules can perform.

Why 70 Degrees Feels Different in London vs. Phoenix

Humidity is the great liar of the temperature world. You’ve heard the phrase "it's a dry heat." There is actual science behind that cliché.

When we talk about what does temperature mean for the human body, we have to talk about evaporation. Your body cools itself by sweating. That sweat evaporates, taking energy (heat) with it into the air. But if the air is already packed to the brim with water vapor—high humidity—your sweat has nowhere to go. It just sits there. You feel miserable because your personal cooling system has been throttled.

This is why a 90°F day in a rainforest can be lethal, while a 90°F day in the Nevada desert is just a reason to wear a hat.

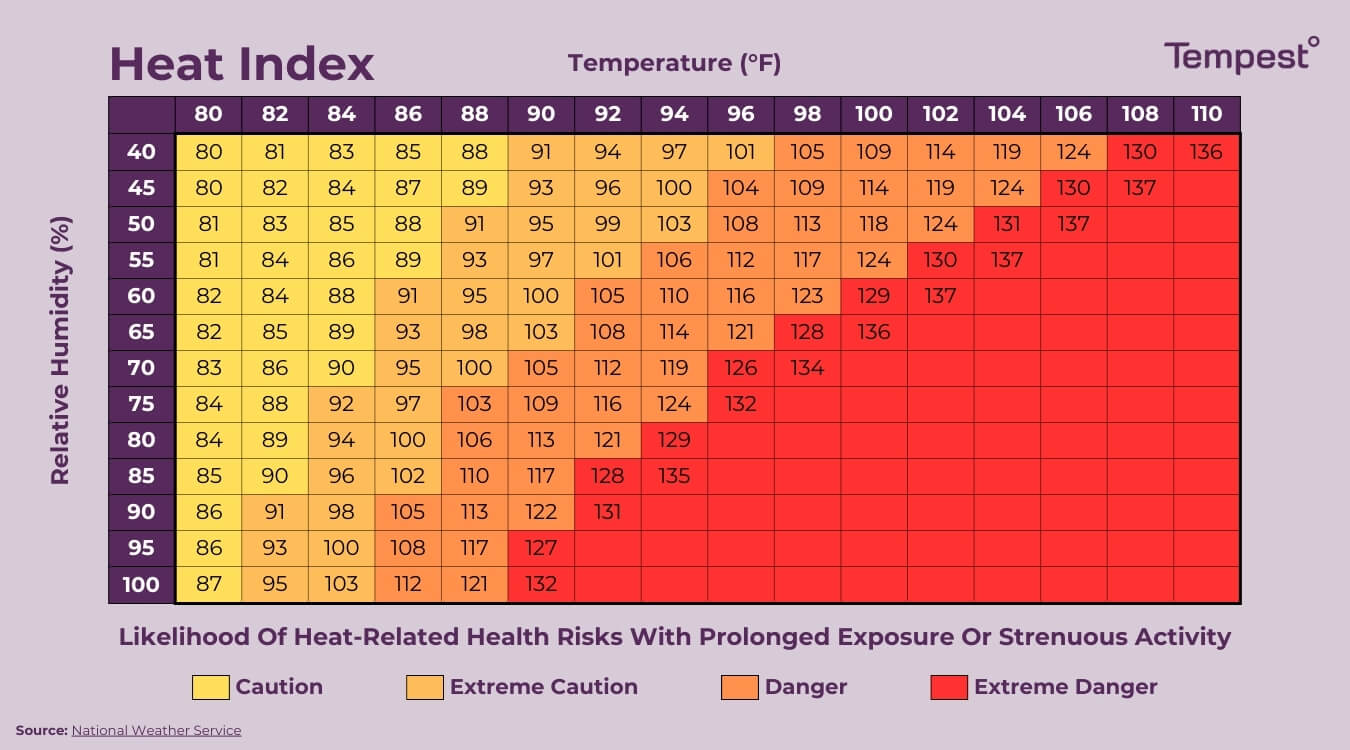

Meteorologists use the "Heat Index" or "Apparent Temperature" to account for this. It’s a way of translating the raw kinetic energy of the air into something that reflects human biology. It’s an admission that the mercury in the thermometer is only giving us a small slice of the truth.

The Strange World of "Negative" Temperature

Now, if you want to get really weird—and physics loves being weird—some scientists have actually achieved what they call "negative temperature" on the Kelvin scale.

👉 See also: How a Circuit Breaker Works: Why Your House Doesn't Just Burn Down

In 2013, physicists at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich created a gas of potassium atoms that reached a sub-absolute-zero state. Now, before you think they broke the laws of thermodynamics, it’s not that they made something "colder" than stopped.

Instead, they manipulated the distribution of energy states. In a normal system, most particles have low energy and a few have high energy. They flipped it. In this inverted state, the atoms were technically at a "negative" temperature. It’s a brain-melting concept that suggests we could eventually create engines with efficiencies greater than 100%, though we’re a long way from that.

How We Actually Measure This Chaos

How do we turn "jiggling molecules" into a number?

Historically, we used mercury. It’s a metal that stays liquid at room temperature and expands very predictably when it gets hit by fast-moving molecules. You put it in a glass tube, the molecules bang against the glass, the glass transfers that energy to the mercury, and the mercury expands upward. Simple.

But mercury is toxic and slow.

Today, we mostly use thermistors or infrared sensors.

- Thermistors: These are in your digital meat thermometers. They measure electrical resistance. As things get hotter, it becomes harder (or easier, depending on the material) for electricity to flow through them.

- Infrared (IR): This is what those "no-touch" forehead thermometers use. Every object with a temperature above absolute zero emits radiation. The hotter it is, the more "excited" that radiation is. The sensor just catches those invisible light waves and calculates the speed of the molecules that sent them.

The Quantum Limit

We used to think we could just keep measuring smaller and smaller until we got a perfect reading. But quantum mechanics says no.

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle tells us that we can't know everything about a particle at once. If you try to measure the temperature of a single atom, the very act of measuring it changes its energy. Temperature, as a concept, only really works when you have a crowd of atoms. It is a "statistical property." You can't have a "temperature" for one lone atom any more than you can have a "parade" with one person. You need a group for the average to mean anything.

This is why deep space is so interesting. People think space is "cold." And it is—about 2.7 Kelvin thanks to the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation left over from the Big Bang. But space is also a vacuum. There are so few molecules that "temperature" almost ceases to have meaning. If you stood in space without a suit, you wouldn't freeze instantly like in the movies. You’d actually overheat first, because there’s no air to carry your body heat away.

Practical Takeaways for Mastering Your Environment

Understanding what does temperature mean isn't just for lab coats. It changes how you live.

1. Optimize your home cooling.

Stop focusing solely on the thermostat number. If you want to feel cooler without dropping the AC to 60, lower the humidity. A dehumidifier does more for your comfort than a five-degree drop in temperature because it allows your skin’s natural "evaporative cooling" to actually work.

2. Cook by energy, not time.

When you sear a steak, you're looking for the Maillard reaction. This happens at roughly 280°F to 330°F. If your pan isn't hot enough, the molecules aren't moving fast enough to break and reform the proteins into those tasty brown crusts. Use an IR thermometer to check the surface of the pan, not just the oven air.

3. Dress for conduction, not just "cold."

In winter, the air isn't what kills you; it's the moisture. Water conducts heat 25 times faster than air. If your base layer gets sweaty, those water molecules will rob your kinetic energy at an alarming rate. Stick to wool or synthetics that move moisture away from your skin.

4. Respect the "Resting" Period.

When you take meat off the grill, the exterior molecules are moving much faster than the interior ones. By letting it rest, you’re allowing those high-speed molecules to collide with the slower ones in the center, equalizing the kinetic energy—aka "temperature"—across the whole cut.

Temperature is the invisible rhythm of the universe. It is the vibration of every atom in your body and every star in the sky. Once you stop seeing it as a number on a screen and start seeing it as a measure of microscopic motion, the world starts to make a lot more sense.

The next time you feel a "chill," remember: your molecules are just looking for a bit more rhythm.

✨ Don't miss: Apple Store Make an Appointment Genius Bar: Why You Can't Just Walk In Anymore

Step-by-Step Thermal Audit:

- Check your insulation: Use a thermal leak detector (or even a damp hand) to find where heat energy is escaping your house.

- Calibrate your tools: Test your kitchen thermometer in a bowl of ice water; it should read exactly 32°F (0°C). If it doesn't, you're not measuring the "mean" kinetic energy correctly.

- Monitor Humidity: Keep indoor levels between 30% and 50% to ensure your body's natural temperature regulation stays efficient.