If you’ve ever joked about being "so OCD" because you like your desk organized or you hate it when your socks don't match, you're not alone. Most people do it. But honestly, it’s a bit of a slap in the face to the millions of people living with the actual clinical diagnosis. When we ask what does OCD mean, we aren't talking about a personality quirk or a love for cleanliness.

It's a monster.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder is a chronic mental health condition where a person has uncontrollable, reoccurring thoughts (obsessions) and behaviors (compulsions) that they feel the urge to repeat over and over. It’s exhausting. Imagine your brain gets stuck on a specific "loop" of a terrifying thought—like your house burning down or you accidentally hurting someone—and the only way to make the anxiety stop is to perform a specific ritual. Even then, the relief is only temporary.

The brain of someone with OCD is basically misfiring. It sends out a "red alert" signal for things that aren't actually dangerous.

The Anatomy of an Obsession: Why Your Brain Won't Shut Up

Obsessions are the "O" in OCD. They are intrusive, unwanted thoughts, images, or urges that cause intense distress. They aren't just worries about real-life problems. They are often bizarre, disturbing, or completely irrational.

A common one is contamination. This isn't just "I hope I don't get the flu." It's a paralyzing fear that every surface is covered in deadly toxins or that by touching a doorknob, you’ve somehow doomed your entire family to a slow death.

📖 Related: Why Female Masturbating in Shower is the Most Practical Form of Self-Care

Other people deal with "Forbidden Thoughts." These are the ones people are too scared to talk about. It might be a sudden, violent image of hitting a pedestrian while driving, even though you’re a safe driver. Or it could be a religious obsession (often called scrupulosity), where a person is terrified they’ve committed an unforgivable sin.

The International OCD Foundation (IOCDF) notes that these thoughts are "ego-dystonic." That’s just a fancy clinical way of saying they go against your actual character and values. If you’re a gentle person who loves animals, an OCD obsession might involve a fear of hurting your pet. That’s why it’s so distressing. It attacks what you care about most.

What Does OCD Mean When it Comes to Compulsions?

If obsessions are the "itch," compulsions are the "scratch."

Compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that a person feels driven to perform in response to an obsession. The goal is to reduce the anxiety or prevent a dreaded event from happening. But here is the kicker: the compulsion often has no logical connection to the fear.

- Checking things (locks, ovens, light switches) dozens of times.

- Counting in specific patterns (only even numbers, or groups of four).

- Repeating words silently or praying a specific number of times to "cancel out" a bad thought.

- Ordering and arranging items until they feel "just right."

- Seeking constant reassurance from friends or family ("Are you sure I didn't hit anyone? Did I look okay?").

The relief found in a compulsion is a trap. It tells the brain, "See? You performed the ritual and nothing bad happened. You better do it again next time." This strengthens the cycle. It’s a physiological feedback loop that’s incredibly hard to break without help.

The Physicality of the Disorder

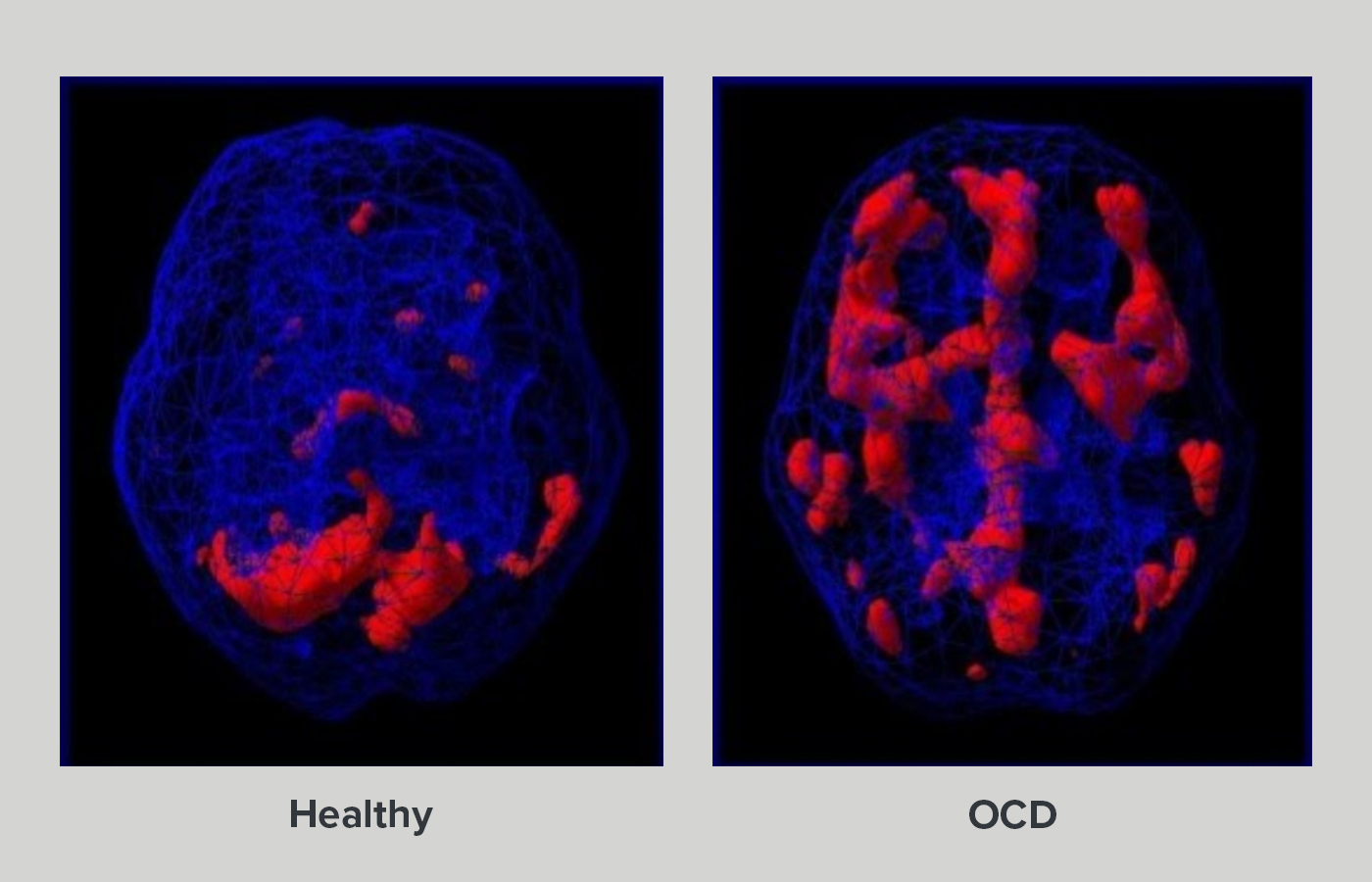

It isn't all in the mind. There’s a biological basis for why this happens. Research using functional MRI (fMRI) scans has shown that people with OCD often have increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and the caudate nucleus.

Think of the caudate nucleus as a "gatekeeper" that filters the thousands of thoughts we have every day. In a typical brain, the gatekeeper lets the important stuff through and tosses the junk. In an OCD brain, the gatekeeper is asleep on the job. The "junk" thoughts—the "what if I left the iron on?" or "what if my hands are dirty?"—get stuck in the loop, circulating between the front of the brain and the deeper structures.

This is why you can’t just "stop thinking about it." You wouldn't tell someone with asthma to just "breathe better," right? Same logic applies here.

Common Subtypes You Might Not Know About

While "washers" and "checkers" are the stereotypes, OCD manifests in ways that are often overlooked.

Pure O (Purely Obsessional)

Some people don't have visible compulsions. They don't wash their hands or check locks. Instead, their compulsions are entirely mental. They might mentally retrace their steps for hours to ensure they didn't do something wrong, or they might perform internal "checks" on their feelings.

Relationship OCD (ROCD)

This involves constant, intrusive doubts about a partner. "Do I really love them?" "Are they the one?" "Is that mole on their face a dealbreaker?" Everyone has doubts, but in ROCD, these questions are agonizing and take up hours of every day, often leading to the end of perfectly healthy relationships.

Harm OCD

This is one of the most misunderstood types. It involves the fear of causing harm to oneself or others. People with Harm OCD are actually less likely to be violent than the general population because they are so terrified of the very idea of violence. They might avoid kitchen knives or stay away from balconies because the "what if" is too loud.

The Diagnostic Criteria: When is it OCD?

Not every ritual is a disorder. Lots of us have "lucky" shirts or a specific way we make coffee. To meet the clinical criteria for OCD, the obsessions and compulsions must be time-consuming (taking up more than one hour per day) or cause significant distress and impairment in work, social life, or other important areas.

Clinicians use the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) to measure the severity. It looks at how much time is spent on these thoughts and how much they interfere with your ability to function. If you’re late to work every day because you spent 45 minutes checking the toaster, that’s a red flag.

Why Does It Happen?

We don't have a single "smoking gun" cause. It’s usually a mix of genetics, brain chemistry, and environment.

If a parent or sibling has OCD, your risk is higher. But it’s not a guarantee. Some researchers, like those at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), are looking at the role of serotonin, though we now know it’s much more complex than just a "chemical imbalance." Glutamate, another neurotransmitter, seems to play a massive role in the "loop" behavior.

There is also a rare form called PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections). In some children, a strep infection triggers an autoimmune response that attacks the brain, causing a sudden, "overnight" onset of OCD symptoms. It’s controversial but gaining more recognition in the medical community.

Breaking the Loop: Treatment That Actually Works

The good news? OCD is treatable. You don't just have to live with the noise.

The gold standard is Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). This is a type of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). In ERP, you are gradually exposed to the things that trigger your obsessions, but you are coached to not perform the compulsion.

If you're afraid of germs, you might touch a "dirty" floor and then sit there with the anxiety without washing your hands. It sounds like torture. It feels like torture for the first few minutes. But eventually, a process called habituation kicks in. Your brain realizes that the "catastrophe" didn't happen and the anxiety naturally drops. Do this enough times, and the brain actually rewires itself.

Medication can also help. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) like Prozac (fluoxetine) or Zoloft (sertraline) are often used, typically at higher doses than those used for depression. They don't "cure" the OCD, but they can lower the volume of the obsessions enough so that the person can actually engage in therapy.

What OCD is NOT

It is not a superpower. You’ll see characters on TV who use their "OCD" to solve crimes or be a perfect accountant. In reality, OCD makes it incredibly hard to focus. It destroys productivity.

It is also not a choice. People with OCD know their thoughts are irrational. They know they don't need to wash their hands for the tenth time. That’s the most frustrating part—being a rational person trapped in an irrational cycle.

Real Steps You Can Take Now

If you think you or someone you love is dealing with this, don't just "wait and see." OCD tends to grow if left untreated. It's a bully; the more you give it what it wants (compulsions), the more it demands.

- Find a Specialist: General therapists are great, but ERP is a specific skill. Look for someone who specifically mentions ERP or is a member of the International OCD Foundation.

- Education is Key: Read books like "The OCD Workbook" or "Brain Lock" by Jeffrey Schwartz. Understanding the "why" can make the "what" feel less scary.

- Stop the Reassurance: If you’re a family member, stop telling the person "everything is fine." It feels helpful, but it’s actually a compulsion that keeps the cycle going. Instead, support them in facing the uncertainty.

- Practice Mindfulness: Learning to observe a thought without reacting to it is a game-changer. You don't have to "solve" the thought. You just have to let it sit there.

OCD is a heavy burden, but the "what does OCD mean" question doesn't have to end in a life sentence of anxiety. With the right tools, you can get your brain back.

To begin moving forward, start by keeping a "trigger log" for three days. Write down exactly what thought triggered your anxiety and what specific action you felt you had to take to fix it. This data is the first weapon you’ll give to a therapist to help map out your recovery. If you aren't ready for a therapist yet, look into the "IOCDF Resource Directory" to find support groups in your area—realizing you aren't the only one with these "weird" thoughts is often the first step toward silencing them.