You're at a restaurant. You see "Chinese" on the menu. Or you're filling out a census form and check a box. Maybe you're hearing someone talk about a "Chinese" dialect that sounds nothing like the one you heard in a movie. Honestly, we use the word constantly, but if you pin someone down and ask what does Chinese mean, they usually stumble.

It's a messy word. It’s a language, but not really. It’s an ethnicity, but also a nationality. It’s a culture that spans five thousand years and several continents. If you think it’s just one thing, you’re missing about 90% of the story.

Let's get into it.

The Language Trap: Mandarin, Cantonese, and the Rest

When people ask "Do you speak Chinese?" they are usually asking if you speak Mandarin. But saying "I speak Chinese" is kinda like saying "I speak Romance." It’s a family, not a single tongue.

The Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family is massive. You've got Mandarin, which is the official language of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan. It’s what most people learn in school. Then you’ve got Cantonese, spoken in Hong Kong, Macau, and by a huge chunk of the diaspora in places like San Francisco or London. They aren't just different accents. If a Mandarin speaker from Beijing and a Cantonese speaker from Guangzhou sit down, they basically can't understand each other’s speech. It’s like a Spaniard trying to understand an Italian. They might catch a word here or there, but the conversation is going nowhere fast.

Then you have Wu (spoken in Shanghai), Min (Fujian and Taiwan), Kejia (Hakka), and dozens of others.

🔗 Read more: Not Your Father's Hard Soda: The Rise, The Fall, and What Drinkers Got Wrong

Here is where it gets weird: the writing. Even if they can't speak to each other, they can often read the same newspaper. The logographic system—those characters we call Hanzi—transcends the sound. The character for "water" is 水. A Mandarin speaker says shuǐ. A Cantonese speaker says seoi2. But the meaning is identical. That's the glue that has held the concept of "Chinese" together for millennia.

The Difference Between Nationality and Ethnicity

Confusion reigns here.

"Chinese" can describe a citizen of the People's Republic of China (PRC). That’s a nationality. It’s a passport. But China is home to 56 recognized ethnic groups. The Han are the majority, making up about 92% of the population. When people think of "Chinese culture," they are usually thinking of Han culture—the tea, the silk, the Confucian ideals.

But what about the Uyghurs in Xinjiang? Or the Tibetans? Or the Hui, the Mongols, and the Zhuang? They are Chinese nationals. They are "Chinese" by law. But ethnically and culturally? They are distinct. They have their own languages, religions (Islam, Buddhism), and histories.

Then flip the script. Look at Singapore. About 75% of Singaporeans are ethnically Chinese. They aren't PRC citizens. They are Singaporean. If you call them "Chinese" in a political sense, they’ll correct you instantly. But in a cultural or "ancestral" sense? Yeah, they’re Chinese. It’s a layers-of-an-onion situation.

The Diaspora: Being Chinese Outside of China

The "Overseas Chinese" or Huayi experience adds another dimension to what "Chinese" means. There are roughly 50 million people of Chinese descent living outside of China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

In Malaysia, the Chinese community has been there for generations, blending Hokkien traditions with local Malay influences to create the unique Peranakan culture. In Peru, you have "Chifa"—a fusion of Chinese cooking and Peruvian ingredients like potatoes and aji amarillo. Is Chifa "Chinese"? Yes. Is it "Chinese" in the way someone in Shanghai would recognize? Probably not.

This brings up the concept of Zhonghua Minzu. It’s a term often used by the Chinese government to describe a "unified Chinese nationality" that includes all ethnic groups within the borders. It’s a political construct designed to create a sense of oneness. But outside those borders, being Chinese is often more about heritage, lunar New Year traditions, and family values than it is about a specific government.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Cup and Saucer Set Might Be the Most Underrated Thing in Your Kitchen

What Does Chinese Mean in the Context of History?

The concept of "China" as a nation-state is relatively new. For most of history, it was a civilization.

Professor Wang Gungwu, a leading historian on the Chinese diaspora, often points out that the identity has shifted from a "world order" (the Middle Kingdom) to a modern nation. In the past, being Chinese meant participating in a specific set of rituals and being part of a specific bureaucracy. If you followed the rites, you were "in."

Today, it's more rigid.

We see this tension in Taiwan. Most people in Taiwan are ethnically Han Chinese. They speak Mandarin. They practice traditional religions. But ask a young person in Taipei if they are "Chinese," and many will say "No, I'm Taiwanese." To them, the word "Chinese" has become so politically tied to the PRC that they’ve distanced themselves from the label, even while keeping the cultural roots.

A Note on "Simplified" vs "Traditional"

You can’t talk about what it means to be Chinese without mentioning the Great Script Divide.

In the 1950s and 60s, the PRC simplified thousands of characters to boost literacy. These are "Simplified Chinese" characters. Singapore followed suit. Meanwhile, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and many overseas communities stuck with "Traditional Chinese."

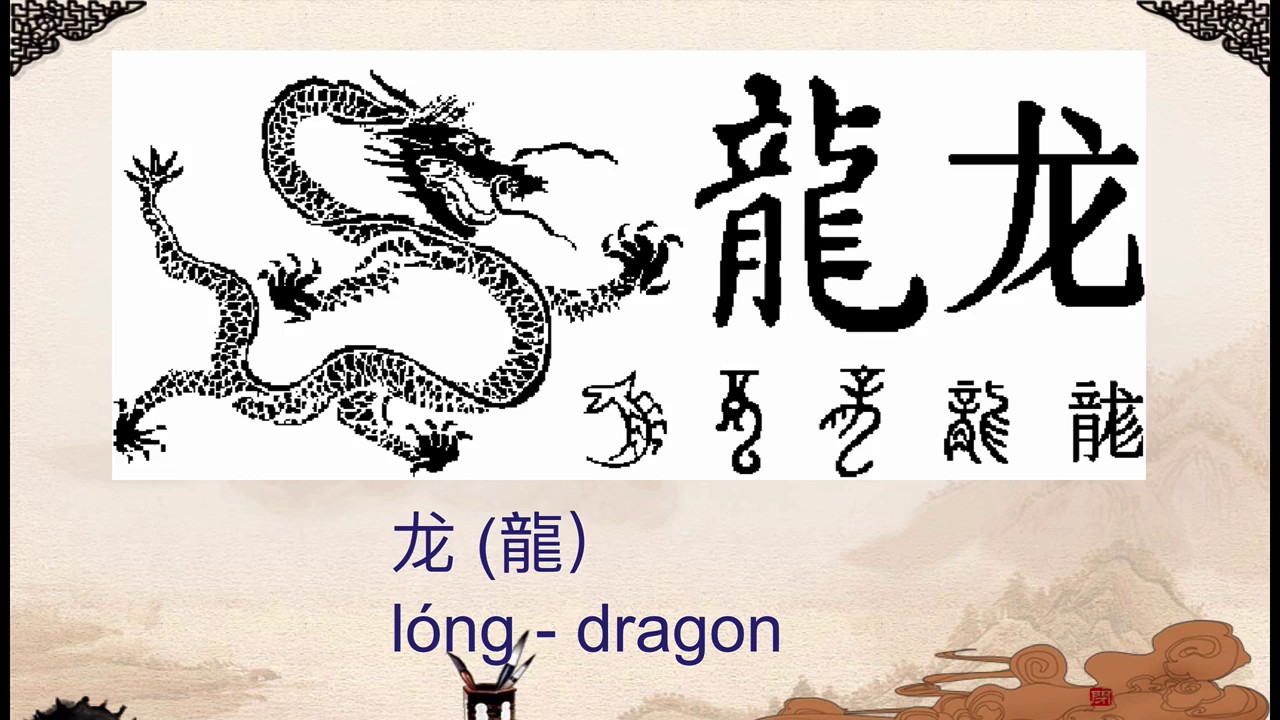

- Traditional: 龍 (Dragon)

- Simplified: 龙 (Dragon)

For some, Traditional characters represent the "true" Chinese soul, carrying the history and etymology of the past. For others, Simplified is just a practical tool for the modern world. This divide is a visual marker of the different paths the Chinese-speaking world has taken over the last century.

📖 Related: Black Gold Jordan 4: Why This Specific Colorway Still Dominates the Resale Market

Common Misconceptions That Need to Die

"Chinese is the hardest language." It depends. The grammar is actually incredibly simple. No verb conjugations (no "I am, you are, he is"). No gendered nouns. No plurals. The hard part is the tones and the memorization of characters. But the "logic" of the language is very accessible.

"Everyone in China speaks the same language." Nope. While Mandarin is the lingua franca, millions of elderly people in rural areas only speak their local topolect. Even "Standard Mandarin" varies wildly in accent from Harbin to Kunming.

"Chinese food is one thing." Americanized takeout is its own beast. Real Chinese food is divided into the "Eight Great Traditions." You have the numbing spice of Sichuan, the light seafood of Cantonese (Yue), the salty and dark sauces of Shandong (Lu), and the sugary, vinegar-heavy dishes of Jiangsu. It’s a continent’s worth of flavor, not a single menu.

How to Respectfully Use the Term

Context is everything.

If you're talking about a person's heritage, "of Chinese descent" is usually the most accurate way to describe someone in the diaspora. If you're talking about the language, try to specify Mandarin or Cantonese if you know which one it is. It shows you’ve done a bit of homework.

And remember that "Chinese" is not a monolith. It’s a huge, sprawling, often contradictory identity that covers 1.4 billion people in China and millions more abroad. It is ancient and it is cutting-edge. It is a script, a set of values, a political entity, and a family lineage all at once.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

If you really want to wrap your head around the complexity of the Chinese identity, start with these three moves:

- Learn the "Han" distinction: Read up on the difference between the Han majority and the 55 minority groups like the Miao, Yao, and Mongols. It changes how you view Chinese internal politics and culture.

- Explore the Diaspora Map: Look into the history of "Coolie" labor in the 19th century and how it led to the vibrant Chinese communities in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and North America.

- Try a Dialect Map: Go to YouTube and search for "Chinese dialects comparison." Hearing the difference between Shanghainese and Mandarin for the first time is a total eye-opener for most people who think it’s all one language.