Verbs are the engines of language. Without them, your thoughts are just a pile of static nouns, sitting there like uncarved marble. Think about it. If you walk into a room and just yell "Coffee!" people might know what you want, but they don't know what's happening. Are you making coffee? Did you spill coffee? Is the coffee sentient and attacking the cat?

You need a verb to make sense of the world.

When people ask what does a verb mean, they usually want a quick definition from a dusty textbook. The standard answer is that a verb is an "action word." But that’s a bit of a lie, or at least a massive oversimplification that makes grammarians like Geoffrey Pullum cringe. If I say "I remain hungry," where is the action? Nothing is moving. I’m just sitting there, being hungry.

A verb is actually a word that conveys an action, an occurrence, or a state of being. It’s the grammatical center of gravity. In English, you literally cannot have a complete sentence without one. Even the shortest sentence in the Bible—"Jesus wept"—functions because "wept" provides the emotional and physical movement.

The "Action Word" Trap and What We Miss

We’ve been taught since second grade that verbs are for jumping, running, and kicking. That’s easy to visualize. But what about words like belong, exist, or seem? These are verbs too. They just aren't doing any heavy lifting in the gym.

Linguists categorize these as "stative" verbs. They describe a state of affairs rather than a physical process. Honestly, these are the ones that actually trip people up when they’re learning a second language or trying to tighten their writing. You can't usually use stative verbs in the continuous tense. You don’t say "I am knowing the answer." You just know it.

Why the distinction matters

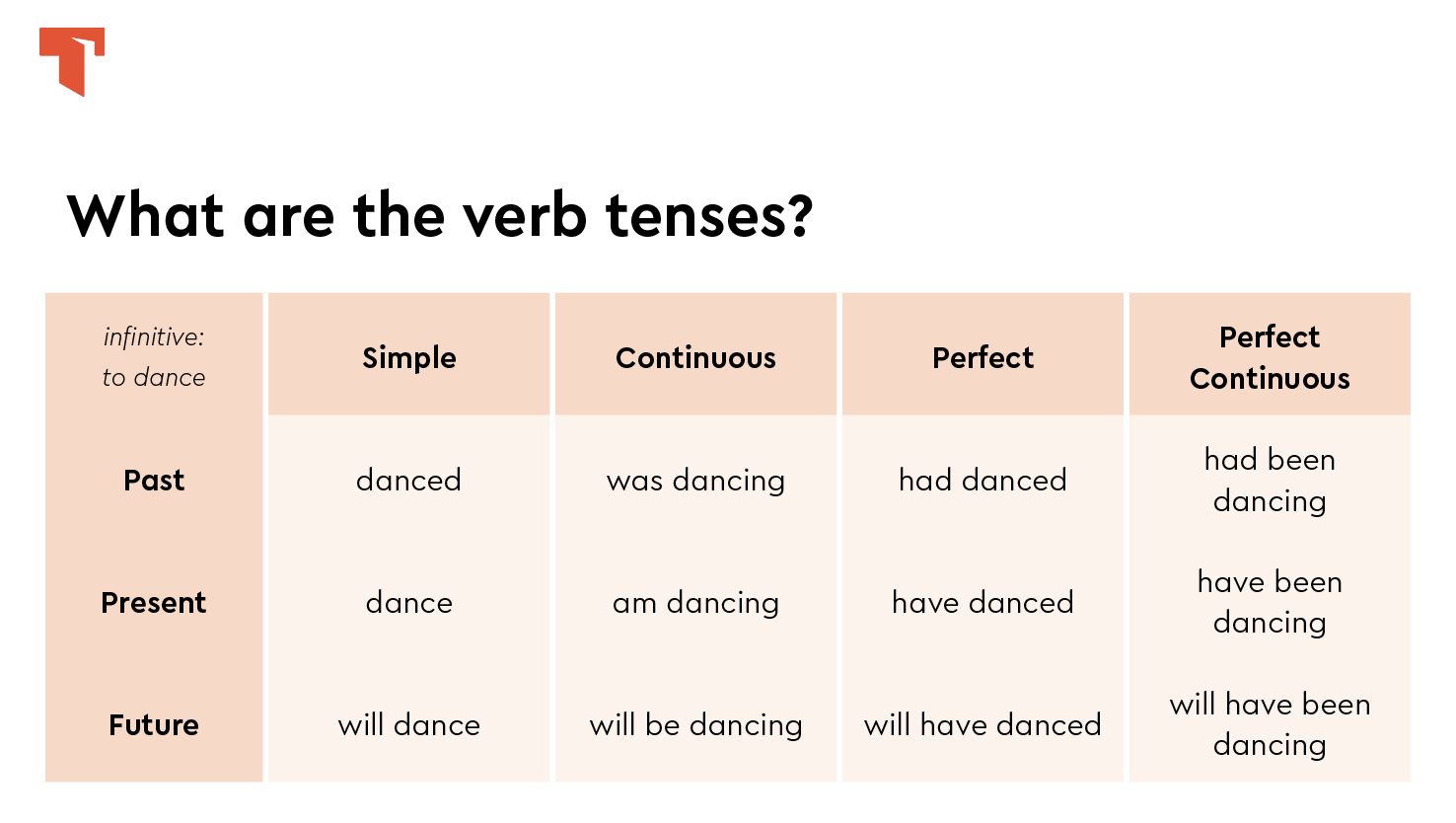

If you want to understand what does a verb mean in a practical sense, you have to look at how they change shape. Nouns are pretty lazy; they might grab an 's' to become plural, but that’s about it. Verbs are shape-shifters. They deal with time. This is called conjugation.

Take the verb "to be." It’s the most common verb in the English language and also the most chaotic. It turns into am, is, are, was, were, be, being, and been. It’s the ultimate state-of-being verb. It’s the glue. Without "to be," we’d all be talking like cavemen, which, while efficient, makes it hard to negotiate a salary or write a poem.

Physical vs. Mental vs. State of Being

To really get what a verb means, you have to see the three main flavors they come in. It's not just "doing" things.

- Physical Verbs: These are the ones your teacher liked. Explode, whisper, dance, typwrite. They describe something you can see or hear.

- Mental Verbs: These happen inside the skull. Believe, guess, wonder, realize. They are just as much "actions" as running a marathon, just localized to your gray matter.

- States of Being: These are the "be" verbs we talked about. They establish a condition. She is a doctor. The soup smells amazing. (Note: "Smells" here isn't something the soup is actively doing with a nose; it’s a state it exists in).

The Power of the Transitive Verb

Sometimes a verb needs a "target" to make sense. This is what we call a transitive verb. If I say "I bought," you’re going to stare at me waiting for the rest of the sentence. I bought what? A car? A taco? A suspicious-looking haunted doll from eBay?

🔗 Read more: Why Every Star Wars Car Windshield Shade Isn't Created Equal

The verb "bought" transfers its action to a direct object.

Intransitive verbs, on the other hand, are self-sufficient. They don't need help. "I slept." "He sneezed." The action starts and ends with the subject. Understanding this distinction is the secret sauce for fixing "run-on" sentences and fragments that plague professional emails. If you use a transitive verb without an object, your reader's brain stays in a state of unresolved tension. It feels like a cliffhanger no one asked for.

What Does a Verb Mean When It’s an Auxiliary?

Sometimes a verb isn't the star of the show; it's the backup singer. These are "helping" verbs or auxiliary verbs.

- I am running.

- She has eaten.

- They will go.

In these cases, "am," "has," and "will" are helping the main verb establish exactly when things are happening. Then you have the "modals"—words like can, could, shall, should, may, might, must. These are incredible because they change the "mood" of the sentence.

Think about the difference between "I wash the car" and "I should wash the car." That one little modal verb "should" adds a whole layer of guilt, procrastination, and social expectation. It changes the reality of the sentence from a fact to a possibility or an obligation. That's the real power of verbs. They don't just report the news; they interpret it.

The Problem with "Passive" Verbs

You’ve probably been told to avoid the passive voice. "The ball was thrown by Jim" vs. "Jim threw the ball."

The meaning of the verb "throw" doesn't change, but the energy of the sentence does. In the passive version, the verb is hidden behind a "to be" helper and a past participle. It feels sluggish. It hides responsibility. Politicians love the passive voice because "Mistakes were made" sounds a lot better than "I made a mistake."

If you want your writing to have a pulse, you need active verbs. You need the subject to do the thing, not have the thing done to it.

Common Misconceptions About Verbs

A lot of people think that if a word ends in "-ing," it’s automatically a verb. Not true.

"Running is fun."

In that sentence, "running" is actually a gerund—a verb acting like a noun. The actual verb is "is." This is where English gets tricky and why "what does a verb mean" becomes a philosophical question. A word’s "verb-ness" depends entirely on its job in the sentence.

Then you have phrasal verbs. These are the bane of anyone learning English. It’s when you take a normal verb and slap a preposition on it, and suddenly the meaning changes entirely.

- "Get" means to obtain.

- "Get over" means to recover.

- "Get by" means to survive.

- "Get at" means to imply.

If you’re just looking at the dictionary definition of "get," you’re missing the forest for the trees. The verb's meaning is contextual and collaborative.

How to Choose Better Verbs

If you want to sound smarter, don’t use more adverbs. Use better verbs.

Instead of saying "He ran quickly," say "He sprinted."

Instead of "She ate hungrily," say "She devoured."

Adverbs are often just crutches for weak verbs. When you pick a precise verb, you don't need the extra baggage. You save space, and you paint a clearer picture in the reader's mind. Mark Twain famously said, "Substitute 'damn' every time you're inclined to write 'very'; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be." The same applies to verbs. If your verb is "walked" and you’re trying to spice it up with adverbs, just find a more descriptive verb like shuffled, marched, or sauntered.

The Functional Reality

At the end of the day, a verb is a claim. It’s an assertion that something exists or something happened. Without them, we have no history, no future, and no present. We just have a list of things.

When you look at a sentence, find the verb first. Once you find it, you find the heart of the message. Everything else—the adjectives, the adverbs, the sprawling prepositional phrases—is just decoration.

To improve your command of language, stop worrying about fancy vocabulary and start focusing on your "predicate." That’s the part of the sentence that contains the verb and says something about the subject. If your predicate is weak, your whole argument is weak.

Immediate Steps to Master Your Verbs

- Audit your last three emails. Look for "is," "was," "are," and "were." Can you replace any of them with a verb that actually does something?

- Kill the adverbs. Look for words ending in "-ly." Delete them and see if you can find a stronger verb to do the job.

- Identify the "state." When you use a verb like "seems" or "appears," ask yourself if you’re being vague on purpose. Sometimes a direct "is" or a concrete action verb is more honest.

- Watch for the "to be" trap. Overusing "There is" or "It is" at the start of sentences usually hides the real subject and verb further down the line. Flip the sentence to put the actor at the front.

Understanding the mechanics of verbs isn't just for English majors or novelists. It’s for anyone who wants to be understood. When you control the verb, you control the narrative. You move from being a passive observer of language to an active participant who knows exactly how to drive a point home.