So, what does a boycott mean, exactly? Most people think it’s just a bunch of angry people on Twitter shouting into the void. It's not. At its core, a boycott is a massive, collective "no thanks" directed at a company, a person, or even a whole country. It’s when you decide to keep your wallet shut to force some kind of social or political change. Honestly, it’s one of the few ways regular people can actually make a billion-dollar corporation sweat.

It works because money is the only language some of these entities speak. If you stop the cash flow, you get their attention. But it’s messy. It’s complicated. And half the time, it doesn't even work the way people think it will.

Where the Term Actually Came From

Believe it or not, the word isn’t some Latin root or legal jargon. It was a guy’s name. Captain Charles Boycott. Back in 1880, in County Mayo, Ireland, Boycott was a land agent for an absentee lord. Times were tough. The local farmers asked for a rent reduction, and Boycott basically told them to get lost. He tried to evict them. The community didn't just get mad; they got organized.

📖 Related: Stash and Dash Schedule 1: Why This High-Speed Logistics Strategy Is Changing the Game

They didn't attack him. They didn't burn his house down. They just stopped talking to him.

Shopkeepers wouldn't sell him food. The postman wouldn't deliver his mail. People in the street looked right through him. It was a total social and economic freeze-out. This was the birth of the modern boycott. It proved that you don't need a weapon to dismantle someone’s power; you just need everyone to agree to walk away at the same time. The Irish Land League turned his name into a verb that has haunted CEOs ever since.

The Difference Between a Boycott and a "Buycott"

You’ve probably seen people doing the opposite lately. That’s a buycott. While a boycott is meant to punish, a buycott is meant to reward. If a company takes a stand you love—maybe they implement a radical new environmental policy—and you go out of your way to spend money there, that's a buycott.

It’s the "carrot" to the boycott’s "stick."

Economically, they serve the same purpose: signaling. You’re telling the market what you value. However, boycotts get way more press because conflict sells. When thousands of people stop buying Bud Light or refuse to shop at Target, it creates a spectacle. Buycotts are quieter. They’re harder to track. But in the long run, they might actually be more effective at building the kind of world people want to live in because they provide a positive incentive for companies to behave.

Does This Stuff Actually Work?

This is where it gets tricky. If you measure success by "did this company go out of business?" then the answer is almost always no. Large corporations are like tanks; they can take a lot of hits before they stop rolling.

But if you measure success by policy change, the record is different.

Take the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955. It lasted over a year. Rosa Parks and thousands of others didn't just stay off the buses for a weekend; they walked to work in the rain for 381 days. It crippled the transit system’s finances and eventually led to a Supreme Court ruling that declared segregated buses unconstitutional. That is the gold standard of what does a boycott mean when it’s executed with discipline.

In the modern era, things are faster. And flimsier.

Social media makes it incredibly easy to start a boycott, but it also makes it incredibly easy for people to forget about it three days later. Research from Brayden King, a professor at Northwestern University, suggests that the biggest impact of a boycott isn't actually the lost sales. It’s the brand damage. When a company is constantly in the news for a boycott, their stock price often dips—not because they're losing millions in revenue, but because investors hate "reputational risk."

Companies hate being the "bad guy" in the news cycle. It makes hiring harder. It makes partnerships awkward. Most companies will settle or change their stance just to make the noise stop.

The "Nestlé" Problem: Why Boycotts Can Last Decades

Sometimes a boycott becomes part of a brand's identity forever. Nestlé is the classic example. People have been boycotting Nestlé since the 1970s over how they marketed baby formula in developing nations.

📖 Related: Construction Worker Stock Photo Secrets: Why Most Sites Look Like Bad Acting

Decades later, people still bring it up.

This brings up a massive challenge for the modern consumer: the "parent company" hurdle. You might want to boycott a specific brand of cereal because of their labor practices, but if you look at the back of the box, they’re owned by a massive conglomerate that owns 500 other brands. To truly boycott some of these entities, you’d basically have to stop eating.

This is why many experts, like those at Ethical Consumer, suggest focusing on "targeted boycotts." Don't try to boycott everything. Pick one specific, achievable goal.

When Boycotts Backfire (The "Streisand Effect")

Sometimes, trying to hurt a company actually helps them. This is sort of what happened with Chick-fil-A years ago. When activists called for a boycott over the company’s donations to anti-LGBTQ+ groups, the opposite happened. Supporters of the company’s stance showed up in droves. Sales actually went up.

This is the risk of the "identity-based" boycott. If you target a company because of their values, you might just end up galvanizing the people who share those values. You end up giving them free advertising.

📖 Related: Peso chileno to USD: Why the Exchange Rate is Doing This Right Now

What Most People Get Wrong About the Impact

People often think that if a boycott doesn't bankrupt a company, it failed. That’s just not true.

Think about the apparel industry. Boycotts against sweatshops in the 90s didn't kill Nike. But they did force Nike—and eventually the entire industry—to adopt much stricter monitoring of their factories. It shifted the "baseline" of what is acceptable.

A boycott is a signal. It tells the people in charge that the social contract has been broken. Even if the boycott fizzles out, the "ghost" of that boycott stays in the boardroom. Executives start asking, "Wait, will this trigger another boycott?" before they make a big decision. That’s real power.

Practical Steps for an Effective Boycott

If you're actually serious about participating in or starting one, you can't just post a hashtag and call it a day.

- Research the parent company. Use tools like "Buycott" (the app) or "Good On You" to see who actually owns what. You might find that the "alternative" brand you’re switching to is owned by the same people you’re mad at.

- Be specific. "I hate this company" isn't a boycott. "I will not buy this product until the company does X" is a boycott.

- Communicate. Write a letter. Send an email. A company needs to know why you aren't buying their stuff. If sales go down and they don't know why, they might just think it’s a bad economy.

- Find an alternative first. A boycott only works if you can sustain it. If you have no other way to get your heart medication, don't boycott the pharmacy. That's just hurting yourself. Find a viable substitute so you can stay in the fight for the long haul.

- Focus on the H2H (Human to Human). Talk to your friends. A single person quitting a brand is a statistic. A neighborhood quitting a brand is a problem.

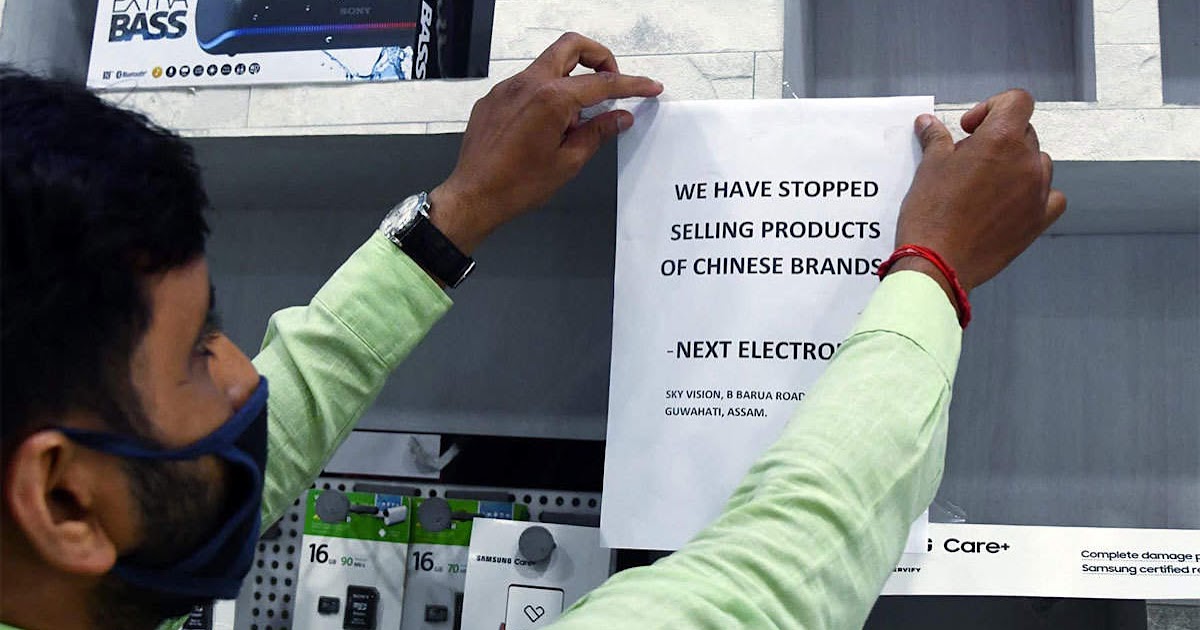

Boycotts are ultimately about the power of the "no." In a world that constantly tells you to consume, to buy, and to click, the act of simply refusing is the most potent tool the average person has. It turns the consumer into a citizen. It’s not just about what you buy; it’s about who you are and what you’re willing to put up with.

To make a boycott count, move beyond the digital outrage. Check your bank statements, find the companies that align with your actual ethics, and move your money there. The most effective way to change a company’s behavior is to make their current behavior too expensive to maintain. Start by identifying one brand in your daily life that contradicts your values and find a local or more ethical replacement this week. Transitioning your spending habits slowly is more effective than a one-day protest that ends with a trip to the same big-box store the next morning.