Ever had that dream where you find a dusty old envelope in your grandpa’s attic and, boom, there’s a crisp one-thousand-dollar bill inside? Most people think these things are just movie props or Monopoly money. But they're real. Or at least, they were very real until the government decided they were making life too easy for the wrong kind of people.

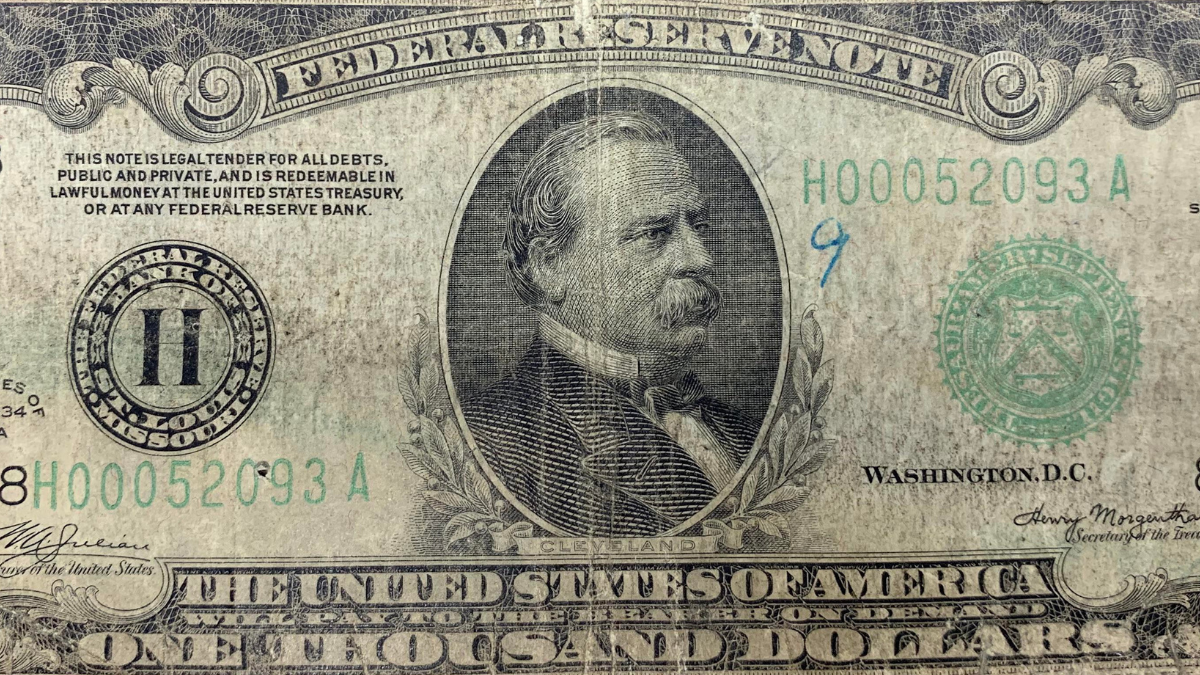

If you’re staring at one right now or just curious about what does a 1000 bill look like, you're looking for Grover Cleveland. Forget Benjamin Franklin—he’s just the $100 guy. On the most common version of the grand, it’s all about the 22nd and 24th President of the United States.

The Face of the Grand: Grover Cleveland

Basically, if you have a "small-size" bill (the same size as the cash in your wallet today), you’re looking at a portrait of Grover Cleveland. This design was standardized back in 1928. He’s right there in the center, looking slightly to his right, framed by an oval.

It’s a bit weird to see him there because we’re so used to the usual rotation of Washington, Lincoln, and Hamilton. But Cleveland was the choice for the 1928 and 1934 series. These are the ones most likely to actually exist in a private collection today. The ink is that classic, heavy black that feels slightly raised if you run your fingernail over his suit.

💡 You might also like: Missouri Paycheck Tax Calculator: What Most People Get Wrong

That Distinctive Green and Blue Seal

One of the fastest ways to tell which era your bill comes from is by looking at the seal to the right of the portrait. Most people are used to the green seal on modern cash.

On the 1,000 dollar note, you’ll usually see:

- The Green Seal: This marks the Federal Reserve Note. Specifically, the 1928, 1934, and 1934A series.

- The Blue Seal: If you see blue, you’ve got a 1918 series. These are "large-size" bills, sometimes called "blanket notes" because they are literally bigger than modern money.

- The Gold Seal: These are rare Gold Certificates from 1928. They literally said you could trade the paper for gold coins. Then the government changed the rules in 1933 and owning them became a legal headache for a while.

The back of the 1928 and 1934 bills is surprisingly boring. No fancy buildings. No Lincoln Memorial or White House. It just says "The United States of America" and "One Thousand Dollars" in giant, ornate lettering surrounded by intricate green lathework. It looks like a high-end certificate of achievement more than a modern banknote.

📖 Related: Why Amazon Stock is Down Today: What Most People Get Wrong

Why You Can't Find Them at the ATM

The Treasury actually stopped printing these in 1945. They didn't officially "discontinue" them until 1969, though. Why? Honestly, it was mostly because of the rise of credit cards and wire transfers. Also, the FBI and Treasury realized that high-denomination bills were a gift to organized crime. It’s a lot easier to carry $100,000 in a slim envelope of thousand-dollar bills than in a heavy suitcase full of twenties.

If you take one to a bank today, they have to take it. It is still legal tender. But here’s the kicker: don’t do that. The bank is required to send it back to the Fed to be shredded. You’d be trading a collector’s item worth anywhere from $2,000 to $10,000 (depending on condition) for exactly $1,000 in boring new bills.

How to Tell if It’s the Real Deal

Counterfeiting wasn't as high-tech in the 30s, but people still tried. If you’re checking a bill, look for the red and blue silk fibers. These aren't printed on the paper; they are in the paper. If you look under a magnifying glass, those tiny hairs should look like they’re part of the fabric.

👉 See also: Stock Market Today Hours: Why Timing Your Trade Is Harder Than You Think

Check the serial numbers too. They should be perfectly spaced and the same color as the Treasury seal. If the numbers look a little "wonky" or the ink doesn't match the seal's shade exactly, you might be looking at a fake. Also, remember that bills from the 1930s don't have the modern security strips or watermarks we see on a new $50 or $100. They relied on "intaglio" printing, which gives the bill that textured, sandpaper-like feel on the portrait.

What to Do If You Actually Have One

First, stop touching it with your bare hands. The oils on your skin can degrade the paper over time, and in the world of currency collecting, a crisp "Uncirculated" grade vs. a "Very Fine" grade can be a difference of thousands of dollars.

- Get a PVC-free plastic sleeve. This keeps the air and moisture out.

- Don’t fold it. Every crease kills the value.

- Check the Series Year. Look for "Series of 1934" or "Series of 1928" near the portrait.

- Look for the District Letter. The black seal on the left has a letter (A through L) representing which Federal Reserve Bank issued it. Some districts are rarer than others.

The market for these is surprisingly liquid. Since there are only about 165,000 of the 1934 series still "in the wild" according to some estimates, collectors are always hunting for them. Whether it’s a "Grand Watermelon" note from the 1890s or a standard 1934 Cleveland, you’re holding a piece of history that’s worth way more than its face value.

The best next move is to check the "Plate Position Number." It’s a tiny letter and number combo on the front, usually in the top left or bottom right. This can help a professional grader tell exactly which sheet of paper your bill came from, which is the first step in getting a formal appraisal.