You've probably seen the headlines. A massive tech company finally hits the stock market, the founders are suddenly billionaires, and retail investors are scrambling to get a piece of the action before the "moon mission" begins. But if you're sitting there wondering what do ipo mean in a practical, day-to-day sense, you aren't alone. It’s one of those financial terms people throw around like everyone already has an MBA, but the mechanics are actually pretty gritty once you peel back the gloss of the New York Stock Exchange floor.

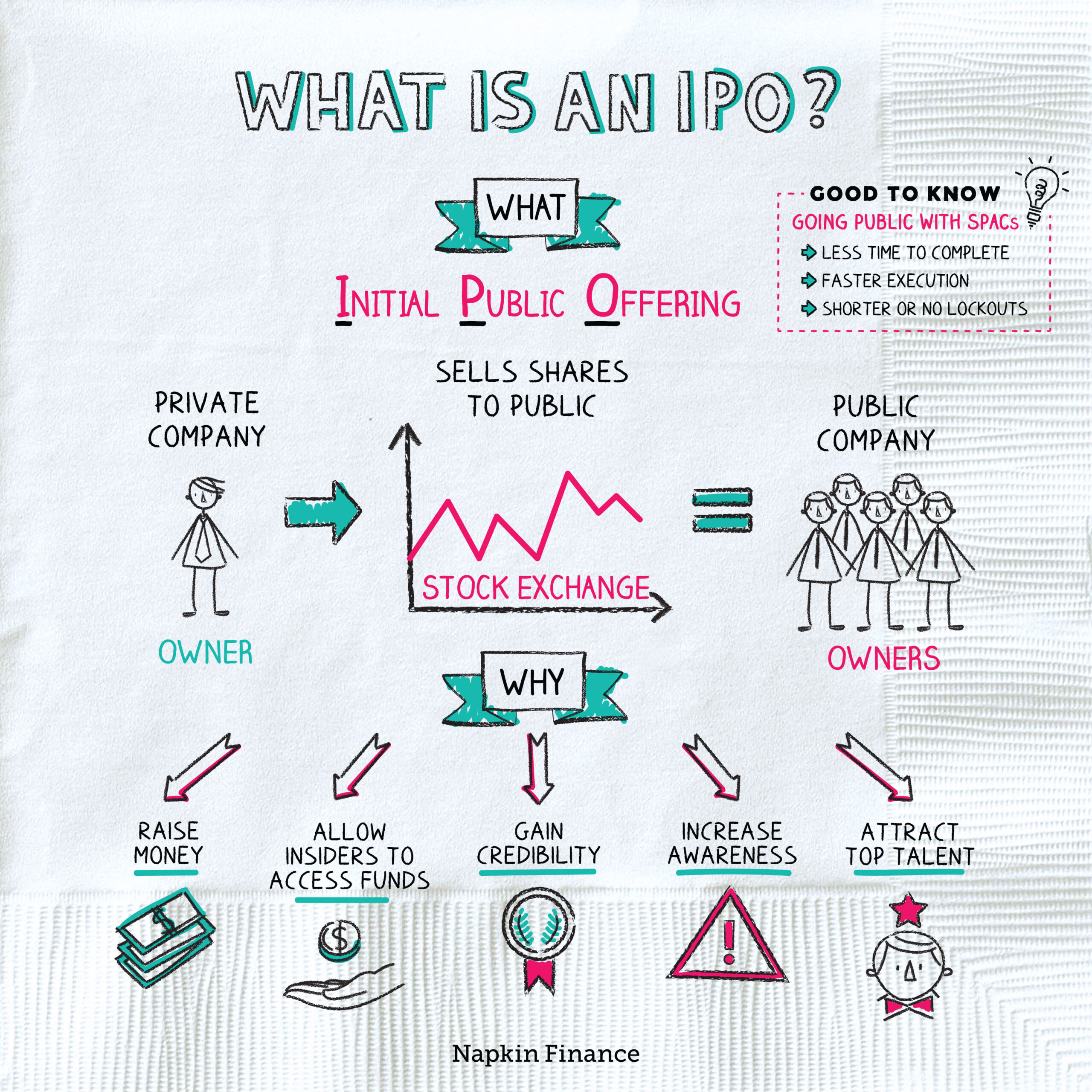

An IPO, or Initial Public Offering, is essentially a company’s "coming out" party.

It’s the first time a private corporation offers its shares to the general public. Before this moment, the company is owned by a small group—usually the founders, some early employees, and venture capitalists who took a massive gamble on the idea when it was just a pitch deck in a garage. When they go public, they're basically saying, "We need more cash to grow, and we’re willing to trade pieces of our company to get it from you."

Why companies actually pull the trigger on an IPO

Money. Honestly, that’s the biggest driver. When a company stays private, it has to rely on bank loans or private funding rounds, which eventually dry up or come with too many strings attached. By launching an IPO, a business can tap into a massive pool of capital from millions of investors.

They use this cash for all sorts of things. Sometimes it’s to build a giant new factory. Other times, it's to pay off old debts that have been suffocating their cash flow.

But there’s a psychological side to it, too. Being "public" gives a company a certain level of prestige. It tells the world—and their competitors—that they’ve made it. It also provides an "exit" for those early investors. Imagine you put $50,000 into a friend's startup ten years ago. You’re "rich" on paper, but you can’t exactly use those private shares to buy a house. An IPO turns those "paper gains" into actual, tradable liquid assets.

The quiet period and the hype machine

Before the ticker symbol ever flashes on a screen, there’s a period of intense legal maneuvering. The SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) doesn't just let anyone start selling stock. The company has to file a Form S-1. This is a massive, often boring document that lays out every single risk the company faces. If you want to know what do ipo mean for a specific brand, read the "Risk Factors" section of their S-1. It's the one place where they are legally required to stop being optimistic and start being honest about how things could go horribly wrong.

🔗 Read more: Is The Housing Market About To Crash? What Most People Get Wrong

During the "quiet period," the company's executives aren't allowed to hype the stock. They can't go on CNBC and tell everyone it's a "guaranteed win." This is to prevent them from artificially inflating the price before the launch.

How the price is actually set (It’s kind of a dark art)

You might think the price of an IPO is based on some perfect mathematical formula. It’s not. It’s a negotiation.

The company hires investment banks—think Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley—to act as "underwriters." These bankers go on a "roadshow," basically a high-stakes sales pitch to big institutional investors like pension funds and hedge funds. They ask these big players, "How much would you pay for 5 million shares?"

Based on that feedback, the bankers set an initial price range.

- If the big funds are excited, the price goes up.

- If everyone is skeptical, the price gets slashed.

- Sometimes, the IPO gets canceled entirely if there isn't enough interest.

On the night before the stock starts trading, the final price is set. This is the price the "big fish" pay. By the time you and I can buy it on an app like Robinhood or E-Trade the next morning, the price has often already "popped" or "dropped" based on early demand.

The "Pop" vs. the "Flop"

When a stock opens at $20 and immediately jumps to $30, people call it a "pop." This looks great in the news, but it actually means the company might have left money on the table. They sold those shares for $20 when people were clearly willing to pay $30.

💡 You might also like: Neiman Marcus in Manhattan New York: What Really Happened to the Hudson Yards Giant

A "flop" is the opposite. Look at the Uber IPO in 2019. It was one of the most anticipated events in years, but it opened below its IPO price and stayed there for a long time. It was a massive reality check for the "growth at all costs" mentality.

The strings attached to being public

Once the confetti is swept up, life changes for the company. They are no longer just answerable to themselves; they have to answer to the public.

Every three months, they have to release an earnings report. If they miss their profit targets by even a penny, the stock can crater. This creates a lot of short-term pressure. Some experts, like Elon Musk, have famously complained that being public forces companies to focus on the next three months instead of the next ten years.

There's also the "Lock-up Period." Insiders and employees usually can't sell their shares for 90 to 180 days after the IPO. This prevents the market from being flooded with shares all at once, which would crash the price. When that lock-up period ends, you often see a second wave of volatility.

Direct Listings and SPACs: The new kids on the block

Recently, the traditional IPO has had some competition. Companies like Spotify and Slack chose a "Direct Listing." They didn't issue new shares or hire expensive underwriters to set a price. They just listed their existing shares on the exchange and let the market figure it out. It’s riskier, but cheaper.

Then there are SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies). These were huge a couple of years ago. Basically, a "shell company" goes public first just to raise a pile of cash, and then it goes looking for a real company to merge with. It’s a backdoor way to go public without the scrutiny of a traditional IPO process. Many of these have performed poorly recently, so the hype has cooled off significantly.

📖 Related: Rough Tax Return Calculator: How to Estimate Your Refund Without Losing Your Mind

Is buying an IPO a good idea for you?

Let’s be real: for most individual investors, buying an IPO on day one is a gamble.

You’re competing against high-frequency trading bots and institutional investors who have teams of analysts. Often, the "smart money" has already made their profit by the time the stock hits your brokerage account.

Specific historical data shows that many IPOs actually underperform the broader market in their first year. For every Amazon or Google, there are dozens of companies that never reclaim their initial hype.

What to look for before hitting "buy"

- Revenue Growth: Is the company actually making more money every year, or just spending more?

- Path to Profitability: Many tech startups lose millions of dollars a year. Do they have a plan to actually make a profit, or are they just hoping to grow forever?

- Market Conditions: In a "bear market" where everyone is scared, even good IPOs tend to struggle.

- The "Why": Why are they going public now? Is it because they need growth capital, or are the original investors just looking for a way to bail out?

Moving forward with your investment strategy

Understanding what do ipo mean is really about understanding the transition from a private dream to a public business. It’s a milestone, not a finish line.

If you're looking to get involved in the next big market debut, the best thing you can do is avoid the FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out). Don't let a flashy marketing campaign or a charismatic CEO convince you to dump your life savings into a stock you don't understand.

Next Steps for the Savvy Investor:

- Read the Prospectus: Go to the SEC’s EDGAR database and search for the S-1 filing of a company you're interested in. Skip the "Letter from the Founder" and go straight to the "Consolidated Financial Data."

- Watch the First 180 Days: Instead of buying on day one, watch how the stock behaves during its first two quarters. See how it handles its first earnings call and what happens when the lock-up period expires.

- Check the Underwriters: Look at which banks are backing the deal. Large, reputable banks usually do more "due diligence" than smaller, obscure firms.

- Diversify: If you must buy into an IPO, make it a small percentage of your portfolio. Never bet the house on a company that hasn't had to prove itself to the public market yet.

The market is full of stories of people who got rich on IPOs, but it's also littered with the portfolios of people who bought at the peak of the hype. Being an expert means knowing when to jump in—and more importantly, when to sit on the sidelines and wait for the dust to settle.