Everyone thinks they know the story. Two guys from Ohio who fixed bikes, went to a windy beach in North Carolina, and somehow stumbled into the sky. It’s the classic American myth. But honestly, if you look at the raw data and the actual engineering logs from 1903, the "luck" part of the story evaporates.

So, what did the Wright brothers do that actually mattered?

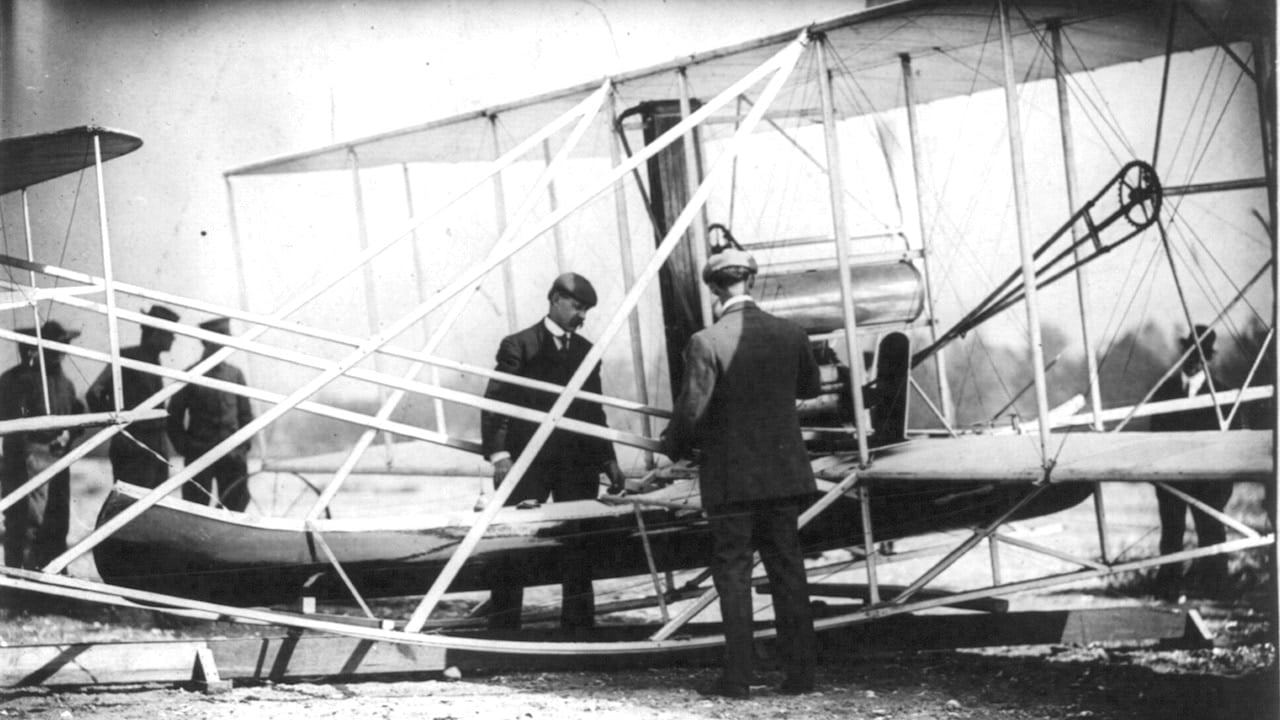

They didn't just build a plane. They solved a physics problem that was killing people. Before Orville and Wilbur, "flight" was mostly just a bunch of brave (and often doomed) men strapping themselves to gliders and hoping the wind stayed steady. The Wrights weren't just mechanics; they were arguably the first true aeronautical engineers who understood that a flying machine isn't just a vehicle—it’s a balancing act.

The Three-Axis Secret

Most people assume the big hurdle was lift. It wasn't. We already knew how to make things go up. Octave Chanute and Otto Lilienthal had been playing with gliders for years. The real nightmare was control.

👉 See also: Why the 13 inch MacBook Air Is Still the Only Laptop Most People Should Buy

Imagine trying to drive a car where the steering wheel only works sometimes, and there are no brakes, and also the road is moving. That’s what early flight was like.

The Wright brothers realized that a plane needs to move in three dimensions simultaneously. They developed three-axis control:

- Pitch (nose up or down)

- Yaw (nose left or right)

- Roll (wings tilting)

They came up with "wing-warping." By literally twisting the tips of the wooden wings with wires, they could make the plane bank like a bird. This was the "Aha!" moment. While everyone else was trying to build "inherently stable" machines that would just stay flat, the Wrights built an unstable machine that a human could steer. It’s the difference between a stable tricycle and a bicycle you have to balance. The bicycle is harder to learn, but it’s the one that actually goes places.

The Wind Tunnel Nobody Mentions

In late 1901, the brothers were ready to quit. They were frustrated. The data they’d been using from famous scientists like Samuel Langley and John Smeaton was wrong. The math didn't add up. Their gliders weren't performing the way the "experts" said they should.

So, they did something radical.

They built a six-foot-long wooden box in the back of their shop in Dayton. They used a scrap engine to blow air through it. This was one of the first wind tunnels. They tested over 200 different wing shapes—tiny little metal scraps they called "airfoils."

They stopped guessing.

They threw out the old books. They realized the "Smeaton Coefficient," a mathematical constant used to calculate lift for over 100 years, was off by about 40%. Because they did the boring, tedious work of measuring drag and lift on tiny pieces of metal, they discovered that long, narrow wings were way more efficient than short, fat ones. Without that wind tunnel, the Flyer would have stayed on the ground. Forever.

Forget the Engine, Look at the Propeller

Propellers are just spinning wings. That sounds obvious now, but in 1903, it was a revelation.

Wilbur and Orville looked at ship propellers and realized they wouldn't work in the air. Water is thick; air is thin. They had to invent an aerial propeller from scratch. They used their wind tunnel data to realize that a propeller needs to have a twist in it so that the tip—which travels much faster than the hub—still bites the air at the right angle.

Their first propellers were about 66% efficient. That’s insane for 1903. Even today, modern high-tech props only get into the 80s or low 90s. They were working with wood and hand tools, yet they nailed the fluid dynamics better than almost anyone in the 20th century.

👉 See also: Folding iPhone Release Date: What Most People Get Wrong

The 12-Second Flight That Reset History

December 17, 1903. Kitty Hawk.

It was freezing. The wind was ripping at 27 miles per hour. Orville climbed in. The engine—a custom-built 12-horsepower block they had to make themselves because no car company would help them—started roaring.

He moved only 120 feet.

That’s shorter than the wingspan of a Boeing 747. It lasted 12 seconds. But it was the first time a machine took off under its own power, landed at a point as high as where it started, and did so under the full control of a pilot.

People didn't believe them at first. The Dayton Daily News barely gave it a mention. The world was skeptical because so many "aviators" had claimed to fly and then crashed into a lake. The Wrights didn't care about the press. They went back to Ohio and spent the next two years flying in a cow pasture called Huffman Prairie, perfecting the turns until they could stay up for half an hour.

Why We Still Care About What the Wright Brothers Did

If you look at a modern F-35 or a tiny Cessna, the DNA of the 1903 Flyer is still there. The way we turn a plane today—using ailerons to roll—is just a high-tech version of Wilbur’s wing-warping.

They didn't just "invent the airplane." They invented the science of flying.

They proved that you can't just throw enough horsepower at the sky and hope to stay up. You need a system. You need to understand the invisible forces of lift and drag. They were the first to treat the pilot as part of the machine, not just a passenger.

How to Apply the Wright Brothers' Mindset Today

- Question the "Smeaton Coefficients" in your life. If the standard industry data isn't working for your project, stop trying to force it. Build your own "wind tunnel" and test the variables yourself.

- Prioritize control over power. Whether you're building a startup or a piece of software, don't just focus on "lift" (growth). Focus on the "three-axis control" (sustainability and pivotability).

- Iterate in private. The Wrights didn't do public demonstrations until 1908, five years after their first flight. They perfected the tech while the world was still laughing at the idea of flight. Master your craft before you ask for the spotlight.

The real legacy of what the Wright brothers did isn't found in a museum in Washington D.C. It’s found in the fact that you can buy a ticket, sit in a pressurized tube, and cross the Atlantic while eating pretzels. They took the "impossible" and turned it into a math problem. Then, they solved the math.

👉 See also: MagSafe Phone Wallet: What Most People Get Wrong About Magnetic Accessories

To truly understand the impact, one should look at the original 1903 blueprints and compare the airfoil curvature to modern gliders; the similarity is striking and proves that their fundamental grasp of physics was decades ahead of its time. You can find these digitized records through the Library of Congress or the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum archives. Reading Wilbur's personal letters to Octave Chanute provides the clearest picture of their iterative failures—the parts of the story that rarely make it into the textbooks but are actually the most valuable for anyone trying to build something new.

Focus on the mechanics of their control system rather than just the fact that they flew. That's where the genius lived. That's what changed everything.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Research the "1901 Wind Tunnel Experiments" to see the raw data charts they created; it’s a masterclass in the scientific method.

- Visit the Wright Brothers National Memorial if you're ever in the Outer Banks to see the actual distance of those first four flights marked on the ground—it’s smaller than you think, which makes the achievement feel more real.

- Apply "Three-Axis" thinking to your current complex projects: are you managing the pitch, roll, and yaw of your goals, or just hoping for lift?