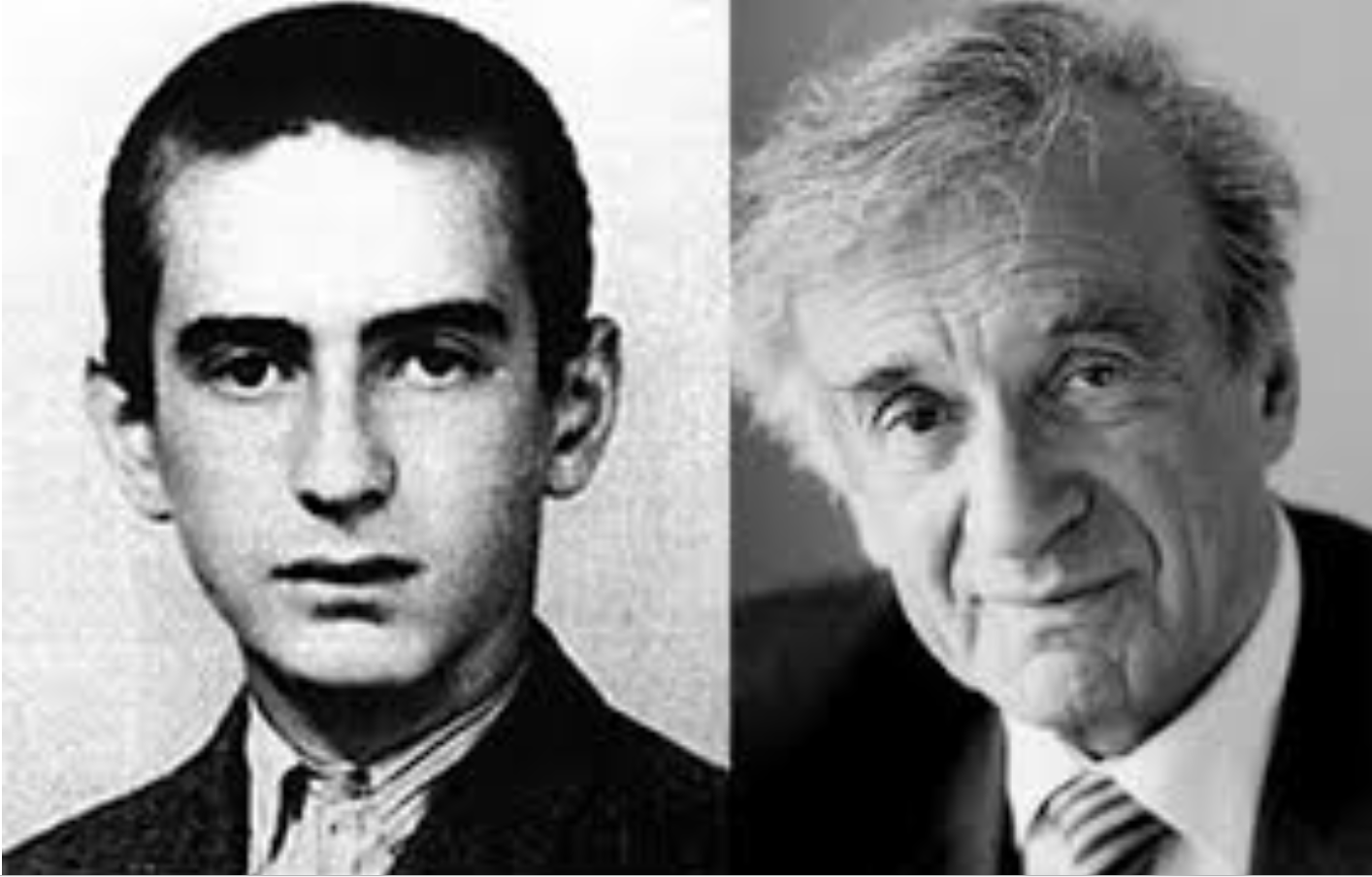

When the gates of Buchenwald finally swung open on April 11, 1945, Elie Wiesel was sixteen years old, skeletal, and effectively alone in the world. He had watched his father die just months earlier. His mother and younger sister, Tzipora, were already gone, murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. For a long time, historians and students focused so much on those "Night" years that we sort of forgot the man lived another seven decades. So, what did Elie Wiesel do after the Holocaust? Honestly, he didn't just "survive." He spent the next seventy-one years trying to make sense of a world that had tried to erase him, eventually becoming the moral compass for an entire generation.

He didn't start by writing. In fact, he took a ten-year vow of silence. He was terrified that words would betray the memory of the dead—that human language was too "thin" to hold the weight of the chimneys. Instead, he moved to France, studied at the Sorbonne, and became a journalist.

The Decade of Silence and the Birth of a Writer

After the war, Wiesel was part of a group of about 400 child survivors sent to France by the OSE (Œuvre de secours aux enfants). He lived in various orphanages, learned French, and eventually found his older sisters, Bea and Hilda, were still alive. That reunion was a rare spark of light in a pretty dark period.

By the late 1940s, he was living in Paris, barely scraping by as a tutor and translator. He eventually landed a gig as a correspondent for the Israeli newspaper Yediot Ahronot. He traveled to Israel, he covered the UN, and he lived the life of a wandering reporter. But the Holocaust? He wouldn't touch it. Not in print.

👉 See also: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

That changed in 1954. He interviewed the French Nobel laureate François Mauriac. Mauriac was a devout Catholic, and during their talk, he kept bringing up Jesus. Finally, Wiesel snapped. He told Mauriac that while the world wept for one child on a cross, thousands of Jewish children had been burned alive in his lifetime, and nobody seemed to care. Mauriac wept. He told Wiesel he had to speak.

The result was an 862-page Yiddish manuscript called Un di Velt hot Geshvign (And the World Remained Silent). It was eventually trimmed down, translated into French, and then into English as Night. It didn't sell well at first. Actually, it took years to find its footing. But once it did, it changed the way the world looked at the 1940s.

The American Chapter: From Reporter to Nobel Laureate

In 1955, Wiesel moved to New York City to cover the United Nations. A year later, a taxi hit him in Times Square. He was in a wheelchair for a year and couldn't travel back to France to renew his papers, so he became a "stateless person" before eventually becoming a U.S. citizen in 1963.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

If you're asking what did Elie Wiesel do after the Holocaust in terms of his personal life, he actually found happiness, though he remained a haunted man. In 1969, he married Marion Erster Rose, who was also a survivor. She became his primary translator and his rock. They had a son, Elisha, named after Elie’s father.

A Timeline of the Later Years

- 1976: He became the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University. He loved teaching more than almost anything else.

- 1978: President Jimmy Carter appointed him as Chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust. This was the seed that eventually became the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

- 1985: He famously confronted President Ronald Reagan in the White House, pleading with him not to visit a cemetery in Bitburg, Germany, where SS soldiers were buried. He told Reagan, "That place, Mr. President, is not your place."

- 1986: He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The committee called him a "messenger to mankind."

More Than Just One Story

Wiesel wrote over 60 books. Think about that for a second. Sixty. He didn't just write about the camps. He wrote about Hasidic masters, the plight of Soviet Jews, and even philosophical novels about the nature of God. He became a global activist. He was in Sarajevo during the Bosnian War, he spoke out about the genocide in Darfur, and he championed the rights of the Miskito Indians in Nicaragua. Basically, if there was an atrocity happening, he felt a personal responsibility to be there. He believed the opposite of love isn't hate—it's indifference.

He also had a bit of a wit. He once joked that he was a "professional survivor," but you could tell the title weighed on him. He felt a crushing debt to those who didn't make it out.

🔗 Read more: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Why What He Did Still Matters Today

Most people think of Wiesel as a tragic figure, but his post-war life was incredibly active. He was the one who pushed for the creation of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. He insisted it be a "living" memorial that focused on contemporary human rights, not just a graveyard of artifacts.

He also struggled with his faith. He never really "found" the God of his childhood again, but he stayed in the conversation. He spent decades arguing with God in his books, which is a very old Jewish tradition. He didn't have easy answers, and he hated people who did.

Actionable Takeaways from Wiesel’s Post-War Life

If you’re looking to apply the lessons from his journey to your own life, here’s how he operated:

- Practice Active Memory: He didn't just remember for the sake of the past; he used memory as a shield for the future.

- Confront Indifference: He argued that staying neutral helps the oppressor, never the victim. In any conflict, "taking a side" is a moral necessity.

- The Power of Teaching: He considered himself a teacher first. He believed that anyone who listens to a witness becomes a witness themselves.

What Elie Wiesel did after the Holocaust was turn a personal nightmare into a universal warning. He died in 2016 at the age of 87, but he left behind a massive blueprint for how to live a life of meaning after unspeakable trauma. He showed that while you can't undo the past, you can absolutely refuse to let it be the end of the story.

To dive deeper into his legacy, start by reading his Nobel acceptance speech, "Hope, Despair and Memory." It’s a short read but carries the weight of everything he spent his life building. You might also visit the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum website to see the archives he helped curate, which now include digitized versions of his personal papers.