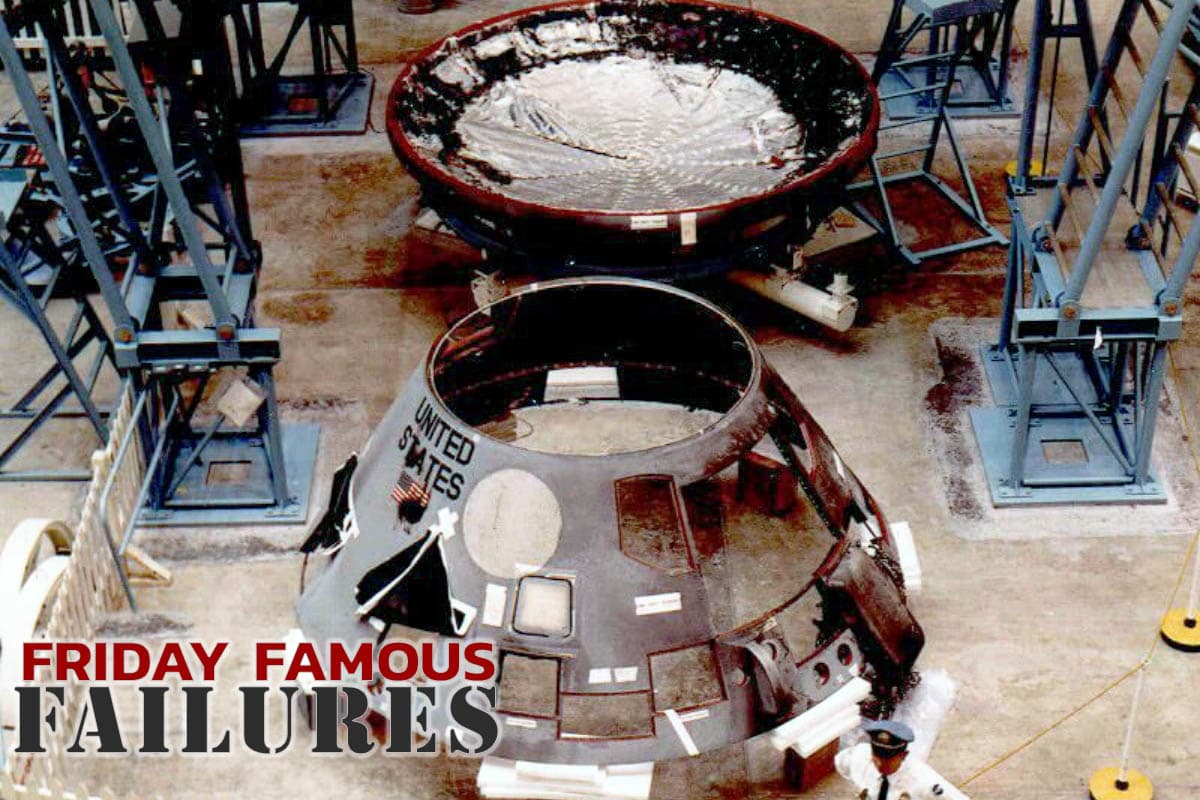

January 27, 1967. It was supposed to be a "plugs-out" test. Basically, a routine dress rehearsal for the first crewed mission of the Apollo program. Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee climbed into Command Module 012 at Launch Complex 34, expecting a long, frustrating day of troubleshooting. They didn't expect to die. But within seconds of a spark hitting the nylon netting inside that cramped cabin, they were gone.

People often look for a single villain. They want a broken wire or a specific bad actor to blame. Honestly, though, what caused the Apollo 1 fire wasn't just a technical glitch; it was a systemic failure of imagination. NASA was sprinting. President Kennedy had set a deadline—the end of the decade—and the pressure was suffocating. North American Aviation (the contractor) and NASA engineers were building a machine more complex than anything in human history, and they were doing it on a terrifyingly tight schedule.

The tragedy of Apollo 1 changed everything about how we go to space. It stopped the program in its tracks, forced a total redesign of the spacecraft, and arguably, saved the lives of every astronaut who followed. If we hadn't had that fire on the ground, we almost certainly would have had a fatal disaster in deep space, where no one could have helped.

The Oxygen Trap: Why the Atmosphere Was a Bomb

If you want to understand the physics of what happened, you have to look at the air the men were breathing. NASA had a long history of using 100% pure oxygen environments. It started with Mercury and continued through Gemini. It’s simpler. Using a two-gas system (like the nitrogen-oxygen mix we breathe on Earth) requires heavy tanks, complex sensors, and the risk of the "bends" if pressure drops too fast.

Pure oxygen is great in the vacuum of space because you can keep the cabin at a low pressure (about 5 psi). At that pressure, fire is manageable. But on the launch pad during a test, NASA did something incredibly dangerous. They pressurized the cabin to 16.7 psi—slightly higher than Earth's atmospheric pressure—using pure oxygen.

This turned the inside of the Command Module into a literal bomb. In a high-pressure, pure-oxygen environment, things that aren't usually flammable become explosive. Velcro? It burns like gasoline. Even the heavy aluminum structure of the ship could theoretically catch fire under the right conditions. This was the fundamental error. NASA knew oxygen was flammable, but they didn't respect how much the pressure increased that risk.

The "Spark" Nobody Could Find

For months after the accident, investigators took that spacecraft apart bolt by bolt. They eventually found it: a small section of wire near the floor, just to the left of Gus Grissom’s seat. The wire belonged to the environmental control system. Because the spacecraft had been through so many design changes, the wiring was a mess. Technicians had been constantly opening and closing panels, dragging tools across bundles of wire.

💡 You might also like: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

The insulation on that specific wire had been chafed away. When the power surged or a door moved, it threw a spark. In a normal room, that spark might have just smelled like burnt plastic for a second. In that 16.7 psi oxygen environment, it was like dropping a match into a puddle of kerosene.

Design Flaws and the "Death Trap" Reputation

Gus Grissom hated this ship. He really did. He once hung a lemon on the flight simulator because he was so frustrated with how many things were breaking. He complained about the communications systems constantly. In fact, right before the fire broke out, he was arguing with the control room because he couldn't hear them through the static. "How are we going to get to the Moon if we can't talk between two or three buildings?" he famously asked.

The complexity was the enemy. North American Aviation was building the Block I spacecraft, which was never even meant to dock with a Lunar Module. It was a bridge to the real moon ship, the Block II. Because it was a "temporary" design in many ways, some safety features were overlooked or compromised for the sake of speed.

The Hatch: A Fatal Engineering Decision

Perhaps the most heartbreaking part of the story is the door. The Apollo 1 hatch was a three-part, inward-opening design. Engineers designed it that way so that internal pressure would help keep it sealed tight in space. It made sense for structural integrity.

But physics works both ways.

When the fire started, the internal pressure spiked almost instantly. The heat caused the gases to expand, pressing the hatch shut with thousands of pounds of force. Ed White, known as one of the strongest men in the astronaut corps, was seen on the monitors trying to pull the hatch open. He never had a chance. The pressure differential meant that even a team of ten men outside couldn't have budged that door.

📖 Related: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

It took technicians five minutes to get through the three layers of the hatch. By the time they did, the cabin was filled with thick, toxic smoke. The fire itself had actually gone out because it had consumed all the oxygen and the pressure had caused the hull to rupture, but the damage was done. The astronauts didn't die from burns; they died from inhaling carbon monoxide.

The Cultural Failure: "Go Fever"

We have to talk about the psychology of NASA in 1967. They call it "Go Fever." It’s that feeling when the goal becomes more important than the process. Everyone was so focused on beating the Soviets and hitting Kennedy’s deadline that they started "normalizing deviance." That’s a fancy way of saying they saw problems and just got used to them.

- The Velcro Problem: There were dozens of square feet of Velcro inside the cabin to help astronauts hold things in zero-G. Every bit of it was fuel.

- The Plumbing: The cooling system used ethylene glycol—basically antifreeze. It was corrosive and flammable when leaked.

- The Documentation: Changes were being made to the ship so fast that the manuals didn't match the hardware.

Joseph Shea, the manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, was a brilliant engineer who felt the weight of this failure more than anyone. He had originally planned to be in the capsule with the crew that day to help troubleshoot the comms, but he couldn't find a way to hook up his headset. He spent the rest of his life haunted by the fact that he survived while his friends didn't.

What Really Happened: A Timeline of the Final Seconds

It all happened so fast. If you read the transcripts, it’s chilling.

At 6:31:04 PM, there was a momentary surge in the AC bus 2 voltage. That was likely the spark.

A few seconds later, a voice—likely Chaffee’s—called out, "Hey!"

Then, "Fire!"

At 6:31:06 PM, the fire was already spreading across the floor.

By 6:31:12 PM, the last transmission came through: "We're burning up!"

The entire event, from the first spark to the rupture of the cabin wall, took less than 30 seconds. The sheer speed of a high-pressure oxygen fire is something people struggle to wrap their heads around. It’s not like a campfire; it’s like a blowtorch.

👉 See also: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

The Aftermath and the Redesign

NASA didn't just fix a wire and move on. They tore the Apollo program apart. The subsequent investigation led by Floyd Thompson was brutal and honest. They realized they had been lucky to survive Project Mercury and Gemini with the habits they had developed.

The "Block II" Command Module, which eventually took Neil Armstrong to the moon, was a completely different beast.

- The Atmosphere: They switched to a 60/40 nitrogen-oxygen mix for ground tests and launch. They only transitioned to pure oxygen once they were in space and the pressure could be lowered to safe levels.

- The Hatch: They designed a new, single-piece hatch that opened outward and could be blown off with explosive bolts in an emergency. It could be opened in under five seconds.

- Materials: Almost every flammable material was stripped out. They replaced nylon with Beta cloth, a non-combustible fabric made of glass fibers coated with Teflon.

- Wiring: Every single inch of wiring was wrapped in protective shielding and routed away from high-traffic areas.

Why We Still Talk About Apollo 1

We talk about it because it reminds us that "common sense" is often the first casualty of a high-stakes race. NASA assumed that because they hadn't had a fire yet, their procedures were safe. They mistook a lack of disaster for the presence of safety.

If you visit the Kennedy Space Center today, you can see the hatch from Apollo 1. It’s a somber, heavy piece of metal. It stands as a reminder that spaceflight is inherently a violent, dangerous business. We aren't "meant" to be up there, and the environment will take advantage of the slightest oversight.

The tragedy of Apollo 1 is why the Moon landing happened. Without that reset—without that painful, public reckoning—the mission would have likely failed in a much more spectacular fashion later on. The "Apollo 1 fire" was caused by a spark, fueled by oxygen, and allowed by a culture that forgot how dangerous the vacuum of space really is.

Actionable Takeaways for Future History and Science Enthusiasts

If you’re researching this or just want to dive deeper into the engineering of the era, don't just look at the fire. Look at the "AS-204" (the official name for Apollo 1) investigation reports. They are public record and offer a masterclass in forensic engineering.

- Read "Man on the Moon" by Andrew Chaikin: It is widely considered the definitive account of the era and gives the most human perspective on the Grissom, White, and Chaffee families.

- Watch the footage: There is no footage of the fire itself, but the "plugs-out" test prep footage shows just how cramped and "cobbled together" the early Apollo cabins looked compared to the sleek versions we saw during the lunar landings.

- Understand the Materials: Look up "Beta cloth." It’s an incredible material that we still use in spacesuits today. It was born directly from the ashes of the Apollo 1 fire.

- Visit the Memorial: If you’re ever in Florida, visit the "Ad Astra per Aspera" exhibit. It’s the first time NASA has publicly displayed parts of the Apollo 1 capsule, and it’s a powerful way to pay respects to three men who gave everything for the sake of exploration.

The legacy of Apollo 1 isn't just the fire; it's the 12 men who walked on the moon because of what we learned from it. It's a reminder that in science and technology, our failures are often the most important teachers we have.