In the late 1980s, Wendell Berry looked at a world obsessed with efficiency and asked a question that feels like a gut punch today: What are people for? It’s not a trick question. It’s also not a metaphor. He literally wanted to know why we were working so hard to replace actual human beings with machines, spreadsheets, and "systems" that don't actually care if we live or die.

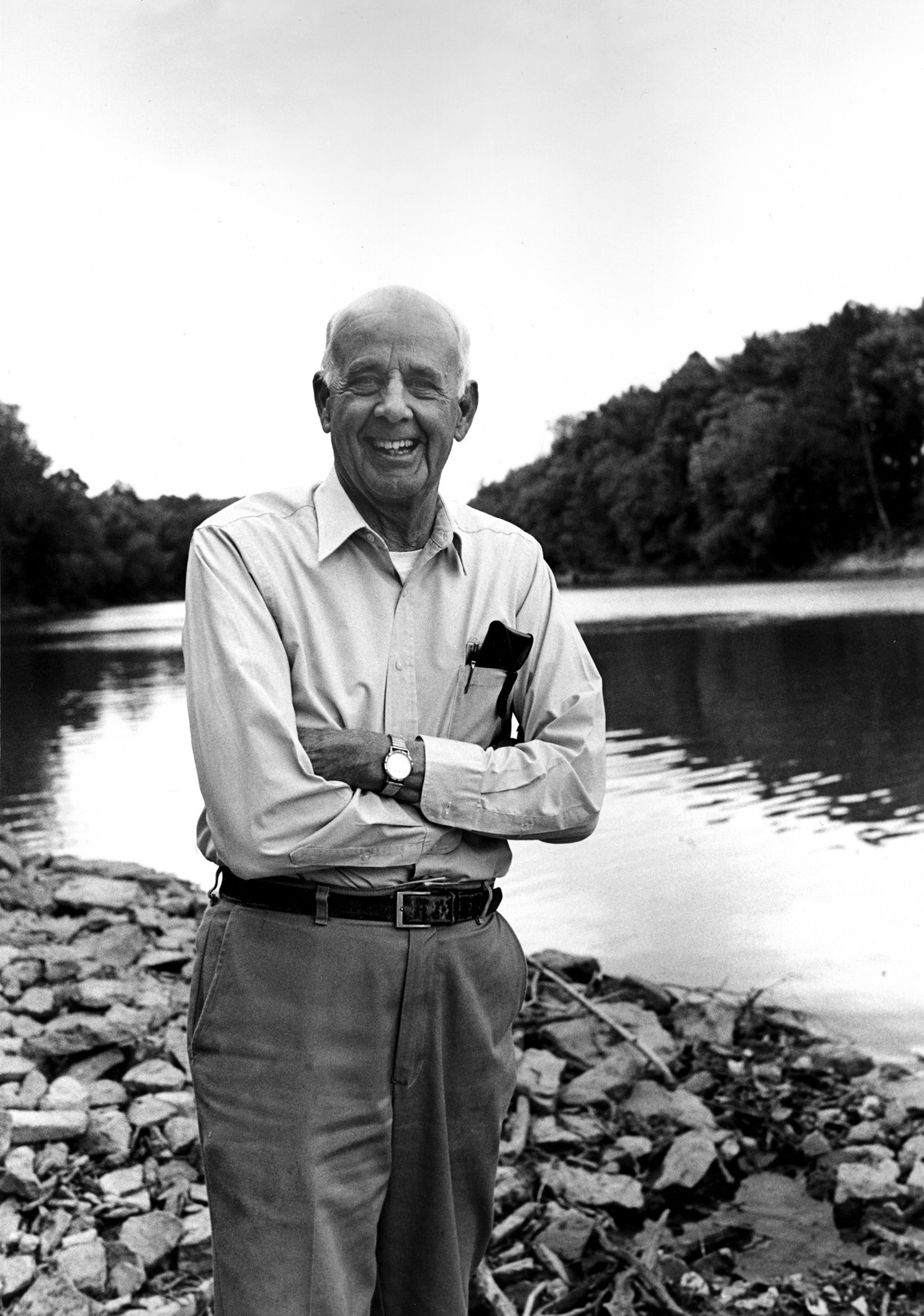

If you’ve ever felt like a tiny, replaceable gear in a giant corporate machine, Berry is the guy you need to read. He’s a farmer from Kentucky. He’s also a poet. But mostly, he’s a guy who realized decades ago that we’ve traded our souls for a faster internet connection and a pre-packaged salad.

The Problem With "Replacing" Ourselves

Most of us think progress is good. Newer is better, right? Berry disagrees. In his 1990 essay collection, What Are People For?, he argues that our obsession with technology and "labor-saving" devices is actually a slow-motion suicide for our culture.

Think about it. We make things easier so we don't have to work. Then we use the time we "saved" to sit in traffic or stare at a screen. Berry points out that when we replace a person with a machine, we aren't just saving money. We’re losing a relationship. We’re losing the specific, local knowledge that only a person can have.

What are people for Wendell Berry? They are for the care of the earth and the care of each other.

When you buy your food from a massive corporation that uses robots to pick, pack, and ship, you’ve removed the human element. There’s no affection there. There’s no "kindly use," as Berry calls it. There is only exploitation. A robot doesn't love the land it’s farming. It just processes it.

The Statistical Mindset

Berry writes a lot about "captains of industry" and agricultural economists. These guys love numbers. They love "efficiency." But you can't measure love, community, or the health of a forest on a balance sheet.

To a statistician, one person is just a unit of labor. If a machine can do it cheaper, the person is obsolete. But Berry argues that a person is never obsolete in a real community. In a small town or a healthy family, you aren't just a "unit." You’re the guy who knows how to fix the tractor, or the woman who knows which herbs grow by the creek.

💡 You might also like: Different Kinds of Dreads: What Your Stylist Probably Won't Tell You

Eating Is an Agricultural Act

This is probably his most famous line. Honestly, it’s one of those things that sounds simple until you actually think about it for more than five seconds.

Basically, every time you eat, you are voting. You’re choosing what kind of world you want to live in. Are you supporting a massive industrial system that poisons the soil and treats animals like widgets? Or are you supporting a local farmer who actually knows the name of the cow?

Berry isn't just being a "foodie." He’s talking about responsibility. If you don't know where your food comes from, you’re basically a "passive consumer." You’re someone who just takes without giving anything back.

- Industrial Eating: Fast, cheap, anonymous, and destructive.

- Agrarian Eating: Slow, often more expensive, but deeply connected to the land.

He even wrote an essay called The Pleasures of Eating. In it, he says that eating with understanding and gratitude is one of the greatest joys a person can have. But if you're just shoveling processed junk into your face while driving to a job you hate, you're missing the point of being alive.

The Economy of Affection

Most people think "economy" means the stock market or the GDP. Berry goes back to the original meaning: oikonomia, or the management of a household.

He talks about his grandfather and the tobacco harvests of the past. It was hard, grueling work. But it was done by hand, with neighbors. They shared meals. They laughed. They watched each other's kids. This is what he calls an "economy of affection."

In this kind of economy, you don't just do things because they’re cheap. You do them because you care about your neighbor. You wouldn't dump toxic waste in the river if you knew your neighbor’s kids were going to swim in it. But a corporation 1,000 miles away doesn't care. They only care about the quarterly report.

📖 Related: Desi Bazar Desi Kitchen: Why Your Local Grocer is Actually the Best Place to Eat

Why He Won’t Buy a Computer

One of the most controversial parts of the book is the essay Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer. People lost their minds over this back in the day. They called him a Luddite.

But Berry’s reasoning was simple:

- He didn't want to be even more dependent on a giant corporation (like the power company).

- He didn't want to speed up his writing process just for the sake of speed.

- He liked the "old-fashioned" way because it kept him connected to his wife, who edited his manuscripts.

He wasn't saying everyone should throw their laptops in the trash. He was asking if we ever stop to consider the cost of our "convenience." What are we giving up to get that extra hour of free time? Usually, it's our independence.

Living in the Great Economy

Berry talks about two different economies. There’s the "Little Economy" (the human one, which is usually messy and flawed) and the "Great Economy" (the Kingdom of God, or Nature).

The Great Economy has rules that humans can't break without paying a price. If you over-farm the land, the soil dies. If you pollute the water, you get sick. It doesn't matter how much money you have in the bank; if the Great Economy fails, we all fail.

What are people for? We are the bridge between these two. We are the ones who have to figure out how to live in the Little Economy without destroying the Great one.

Actionable Steps: How to Live Like a Berry-ist

You don't have to move to a farm in Kentucky to start living this out. Honestly, most of us can't. But you can start reclaiming your "personhood" in small ways.

👉 See also: Deg f to deg c: Why We’re Still Doing Mental Math in 2026

Start a garden. Even if it’s just a tomato plant on a balcony. It forces you to interact with the Great Economy. You realize that you can't "program" a plant to grow faster. You have to wait. You have to care for it.

Buy local. Find a farmer’s market. Talk to the person who grew your carrots. It turns a transaction into a relationship. Suddenly, you aren't just a "consumer"—you're a neighbor.

Do things by hand. Try to fix something instead of throwing it away and buying a new one. There is a specific kind of dignity in manual labor that we’ve almost entirely lost in the modern world.

Limit your dependencies. Look at how much of your life is controlled by giant corporations you’ve never met. Can you bake your own bread? Can you walk to the store instead of driving? Every small step toward self-sufficiency is a way of answering the question of what people are for.

Wendell Berry isn't offering a "quick fix" for the modern world. He’s offering a completely different way of seeing it. It’s a vision where we aren't just users and losers, but members of a community who actually have a purpose.

To start your journey into Berry’s world, pick up a physical copy of What Are People For? from a local independent bookstore. Read one essay at a time, slowly, and then go outside and look at the trees. It's a start.