You’re staring at a screen full of red dots. It’s August, the air smells like a campfire that’s gone horribly wrong, and you’re trying to figure out if that plume of gray-black smoke on the horizon is something you need to run from or just another "controlled burn" that got a little rowdy. Most people pull up a western states wildfire map and assume every red icon is a house-eating inferno. They aren't. Honestly, it’s a bit more complicated than that, and if you don't know how to read the layers, you’re basically just looking at a digital Rorschach test of anxiety.

The West is burning differently now. It’s not just "fire season" anymore; it’s a year-round reality that stretches from the chaparral of Southern California to the deep timber of the Idaho panhandle. Understanding these maps is a survival skill.

Why Your Default Map Might Be Lying to You

Most folks go straight to Google Maps or a quick news site visual. Those are fine for a general "hey, something is on fire over there" vibe, but they lack the granular data needed for real decision-making. These maps often aggregate data from MODIS and VIIRS—satellites that pick up "thermal anomalies."

💡 You might also like: Pablo Escobar Real Photo: The Truth Behind the Most Famous Images

A thermal anomaly could be a 50,000-acre crown fire. It could also be a very hot parking lot or a gas flare.

If you want the real dirt, you have to look at the Integrated Reporting of Wildland-Fire Information (IRWIN) or the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) dashboards. These are the gold standards. They aren't always "pretty," but they are accurate. When you see a "heat perimeter" on a high-end western states wildfire map, that’s often generated by infrared flights (NIROPS) that happen in the middle of the night when the air is cooler. If the map hasn't been updated since 2:00 AM, that "line" you think is safe might have been jumped by a spot fire hours ago. Wind doesn't wait for map updates.

The Smoke Problem

Smoke is actually what kills or sickens more people than the flames themselves. You can be 200 miles away from the nearest ember and still have an AQI (Air Quality Index) of 400.

AirNow.gov is the heavy hitter here. They use a "Fire and Smoke Map" that blends low-cost sensor data (like PurpleAir) with official government-grade monitors. It’s a messy, beautiful mix of "crowdsourced" and "official." Why does this matter? Because official monitors are often spaced too far apart. Your neighbor's PurpleAir sensor might show that the smoke is pooling in your specific canyon while the official city monitor three miles away says everything is "Moderate."

Real-Time Tools and Who to Trust

When the McKinney Fire or the Hermits Peak fire kicked off, the maps were struggling to keep up. That’s where the "Watch Duty" app started gaining massive traction. It’s a non-profit that uses real humans—mostly retired dispatchers and firefighters—to vet the radio traffic and update the map in real-time. It’s basically the "Waze" of wildfires.

But even with a great app, you’ve gotta understand the terminology.

- Containment: This doesn't mean the fire is out. It means there is a fuel break (like a dug trench or a road) around a certain percentage of the perimeter. A fire can be 50% contained and still grow by thousands of acres on its "uncontained" side.

- Confinement: This is a bit of a "bureaucratic" term. It basically means the fire is being allowed to hit a natural barrier like a rock face or an old burn scar.

- Spotting: This is the nightmare scenario. Hot embers can fly over a mile ahead of the main fire front. If your western states wildfire map shows a solid red blob, it might not be showing the tiny new fires starting ahead of it.

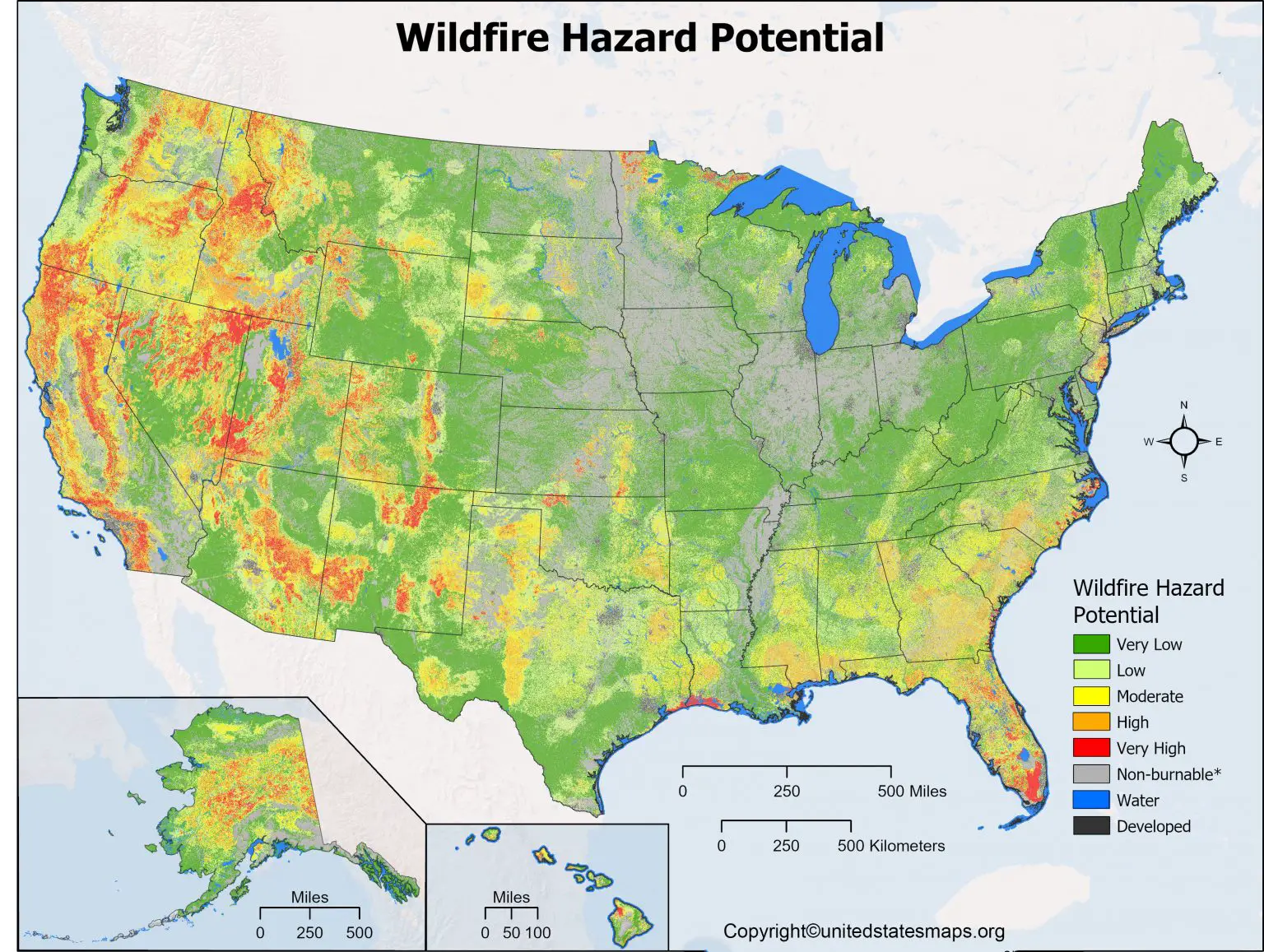

The Geography of Risk in 2026

We are seeing fires in places that didn't use to burn like this. The "Wet Side" of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington is now a powder keg during east-wind events. Colorado’s Front Range is no longer just a summer risk; the Marshall Fire proved that a suburban neighborhood can go up in the middle of December if the grass is dry and the wind is hitting 100 mph.

I talked to a forest hydrologist last year who pointed out something most people miss: Burn Scars.

✨ Don't miss: Tornado Watch South Carolina: Why You Can't Just Ignore the Sky Today

Look at a map of the West from the last five years. It’s a patchwork of previous fires. These scars actually act as "speed bumps" for new fires. If a new fire hits a three-year-old burn scar, it usually slows down because there’s less "fine fuel" (needles, small branches) to burn. But, those same scars are death traps for flash floods. If you see a fire map showing a big blaze uphill from an old burn scar, you aren't just looking at a fire risk—you’re looking at a future mudslide risk when the rains eventually come.

Mapping the WUI

The Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) is the fancy term for "where houses meet the woods." This is where the mapping gets controversial. Insurance companies are now using proprietary, AI-driven wildfire maps to decide who gets dropped. They aren't using the public NIFC maps. They are looking at "fuel load" (how much brush is in your yard) and "slope" (how fast fire moves up your hill).

If you live in the WUI, your personal western states wildfire map needs to include your evacuation routes. Most people have one way out. If the map shows a fire on that road, you’re stuck.

How to Actually Use This Info Without Panicking

It’s easy to get "doomscrolling" syndrome. You see the West glowing orange on a screen and feel like the whole world is ending. It's not. Most fires are small and put out quickly (the "initial attack" success rate is actually quite high, often over 90%). The ones that make the map look scary are the "Megafires."

To stay sane, filter your map views.

💡 You might also like: Trump Putin Meeting Live: What Really Happened in the Latest Talks

- Check the 24-hour heat perimeter. If the edges aren't growing, the crews are likely making progress.

- Look at the wind vectors. A fire five miles away is terrifying, but if the wind is blowing at 20 mph in the opposite direction, you have breathing room.

- Cross-reference with cameras. The ALERTWest camera network is insane. You can literally take control of high-def cameras on mountain tops to see the actual flames. It turns an abstract red dot on a map into a real-world visual.

What’s Missing from the Data?

Maps struggle with "micro-climates." A canyon can create its own weather. A fire can create its own weather—pyrocumulus clouds that generate lightning and downbursts. No western states wildfire map is fast enough to show a sudden 180-degree wind shift caused by a collapsing smoke column.

That’s why you listen to the boots on the ground. If the Sheriff says "Go," you don't check the map to see if he’s right. You just go.

Actionable Steps for the Next Fire Season

Stop relying on one source. Diversify your "map stack" so you aren't blind when one server crashes under high traffic (which happens often during big events).

- Download Watch Duty: It’s the fastest for local updates and "mandatory evacuation" notifications.

- Bookmark the NIFC Interactive Map: Use this for the "big picture" and to see where federal resources (like VLATs—Very Large Air Tankers) are being deployed.

- Learn the NASA FIRMS interface: It’s raw satellite data. It’s ugly, but it shows heat signatures before they are officially "verified" by an incident commander.

- Set up your AirNow "Favorites": Check it every morning. If the AQI is over 100, don't go for that run, even if the sky looks "okay."

- Map your own "Zone": Go to your county’s emergency management website and find your evacuation zone number. When the maps start flashing red, they will call out zones, not necessarily street names.

The Western U.S. is an ecosystem built on fire. It has been for thousands of years. The difference now is us—our houses, our power lines, and our climate. The map is just a tool to help us navigate a landscape that is reclaiming its natural cycle. Use it, but don't let it paralyze you. Stay mobile, stay informed, and for heaven's sake, keep your "go bag" by the door if you see red on that screen.