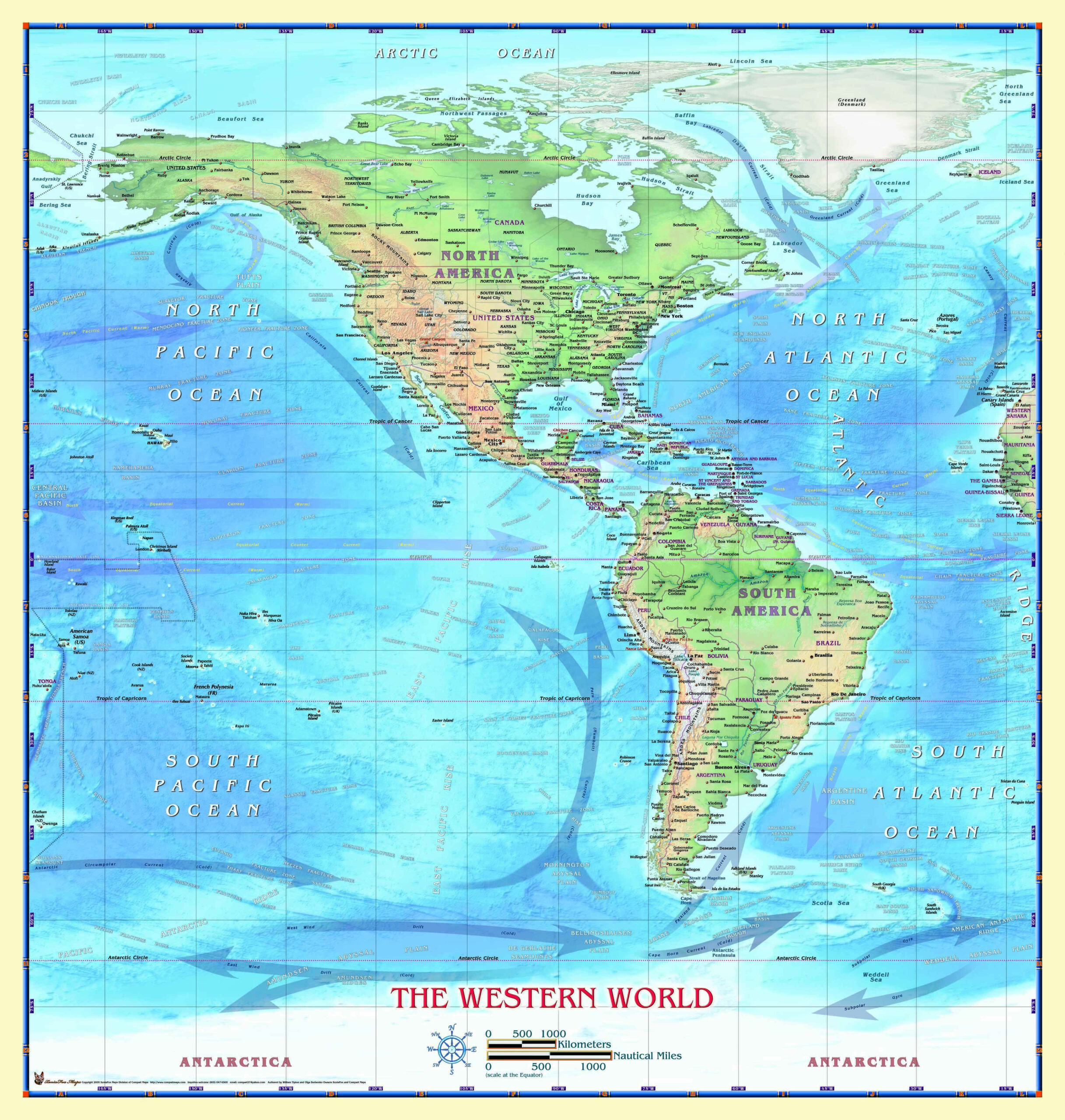

Look at a western hemisphere world map for more than five seconds and you’ll start to realize how weirdly we’ve been taught to view the Earth. It’s basically just half a ball. But which half? If you ask a geologist, a navigator, and a politician, you might get three different answers. Most of us just think "The Americas," but it’s actually way more crowded than that. You’ve got bits of Africa, a chunk of Europe, a massive slice of Antarctica, and enough islands to make your head spin. It’s a mess of longitudinal lines and arbitrary borders that define how we see "The West."

Honestly, the whole concept of a "hemisphere" is a bit of a human construct. The Earth doesn't have a giant seam running down the middle. We just decided, mostly thanks to some British cartographers in the 1880s, that the Prime Meridian should sit in Greenwich. That decision literally split the world in two. Because of that, the western hemisphere world map isn't just a geographical tool; it’s a historical receipt of who held the power when the maps were being drawn.

Where Does the Western Hemisphere Actually Start?

If you want to get technical—and we should—the Western Hemisphere is the half of the Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian and east of the 180th meridian.

It’s not just North and South America. That’s the biggest misconception out there. While the Americas are the "stars" of this particular map, the boundary lines actually cut right through several countries in the Old World. You’ve got the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Algeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Togo, and Ghana. Parts of these places are technically in the Western Hemisphere. If you're standing in Greenwich, London, and you take one step to the left, you've just entered the same "side" of the world as Los Angeles and Lima.

✨ Don't miss: All Star Car Wash: Why This Growing Brand Is Changing the Way We Clean Our Cars

It's kinda wild when you think about it.

The Longitudinal Squabble

Cartography is rarely about just drawing lines. It's about ego. In the late 19th century, there was a huge debate about where the "center" of the world should be. The International Meridian Conference of 1884 is what settled it. They chose Greenwich. The French weren't thrilled—they actually abstained from the vote and kept using the Paris Meridian for decades. But eventually, the Greenwich line became the global standard. This line dictates exactly what appears on your western hemisphere world map today. Without that specific meeting in Washington D.C. over a hundred years ago, your GPS might be reading totally different coordinates right now.

Why Your Map Probably Looks "Wrong"

Most maps you see in a classroom are flat. The Earth is not. This creates the "Orange Peel Problem." If you try to flatten a sphere, something has to stretch.

On a standard Mercator projection, Greenland looks like it’s the size of South America. It’s not. Not even close. South America is actually about eight times larger than Greenland. When you look at a western hemisphere world map, the distortion usually gets worse the further you move from the equator. This is why many modern geographers prefer the Robinson or Winkel Tripel projections. They compromise on everything—shape, area, and distance—to make the map "look" more like the real world.

The Island Problem

Don't forget the Pacific. People always forget the Pacific. A huge chunk of the western hemisphere is just water. But scattered in that water are places like Kiribati, Samoa, and the Aleutian Islands. The 180th meridian—the "backside" of the Prime Meridian—is where things get messy. The International Date Line zig-zags around islands so that countries don't have two different days happening at the same time. On a strict western hemisphere world map, you might see a straight line, but the reality on the ground is a jagged mess of time zones and political compromises.

The Cultural vs. Geographical Divide

We often use "Western Hemisphere" as a synonym for "The Americas." In a political context, this makes sense. The Monroe Doctrine, for example, was all about keeping European powers out of the "Western Hemisphere." But geography doesn't care about politics.

There are plenty of "Western" cultures (in the political sense) that are firmly in the Eastern Hemisphere, like Australia or most of Europe. Conversely, there are many places in the Western Hemisphere that don't fit the stereotypical "Western" mold. It’s a bit of a linguistic trap. If you’re looking at a map for travel or logistics, you need the hard lines. If you’re talking about sociology, the map is almost useless.

Ireland and the Edge of the World

Ireland is almost entirely in the Western Hemisphere. So is Portugal. When you're standing on the cliffs of Moher, you're looking out across the same hemisphere that contains New York City. There's a shared Atlantic history there—the "Atlantic World" as historians like Bernard Bailyn have called it—that links the two sides of this hemisphere far more closely than the lines on a map might suggest.

How to Actually Read a Western Hemisphere World Map

If you're using one of these maps for a project or just for fun, you need to look for a few key markers.

- The Equator: This divides the North and South. In the western hemisphere, this cuts through Ecuador (obviously), Colombia, and Brazil.

- The Tropics: The Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn define the "middle" of the hemisphere. This is where the sun hits directly at least once a year.

- The Prime Meridian: Look at the far right edge of the map. That’s 0°.

- The 180th Meridian: Look at the far left. That’s where the "West" ends.

A Note on Antarctica

People always cut off the bottom of the map. Don't do that. A huge portion of Antarctica sits in the Western Hemisphere. The Antarctic Peninsula, which reaches up toward South America, is one of the most studied places on Earth right now because of climate change. If your western hemisphere world map stops at the tip of Chile, you're missing a massive piece of the puzzle.

Surprising Facts About This Half of the Globe

- The Tallest Mountain: Everyone says Everest, but if you measure from the center of the Earth, it's actually Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador. Because the Earth bulges at the equator, Chimborazo is technically closer to space than Everest is.

- The Driest Place: The Atacama Desert in Chile. Some parts of it haven't seen rain in recorded history. It looks more like Mars than Earth, which is why NASA actually tests rovers there.

- The Most Remote Inhabited Island: Tristan da Cunha. It’s in the South Atlantic, firmly in the Western Hemisphere, and it is incredibly hard to get to. There’s no airport. You have to take a boat from South Africa that takes about a week.

Actionable Steps for Map Enthusiasts

If you’re looking to buy a map or use one for educational purposes, don't just grab the first thing you see on a stock image site. Most of those are riddled with errors or outdated borders.

- Check the Projection: If Greenland looks as big as Africa, throw it out. Look for "Equal Area" projections like the Gall-Peters if you want to see the true size of landmasses, though be warned: it makes the continents look "stretched" vertically.

- Verify the Date Line: Make sure the map clearly shows the difference between the 180th meridian and the International Date Line. They are not the same thing.

- Look at the Poles: A good map shouldn't just fade into white at the top and bottom. It should show the actual landmass of Antarctica and the ice coverage of the Arctic.

- Use Digital Tools for Context: Sites like "The True Size Of" allow you to drag countries across a western hemisphere world map to see how much they actually shrink or grow due to projection distortion. It’s a reality check everyone needs.

- Source from Experts: For the most accurate data, stick to the National Geographic Society or the USGS (United States Geological Survey). They don't take shortcuts with their cartography.

Understanding the western hemisphere world map is really about understanding how we've chosen to organize our world. It's a mix of rock-solid geology and very fluid human history. Whether you're navigating a ship or just trying to win at trivia, knowing where these lines actually fall—and why they were drawn there in the first place—changes how you see the planet.