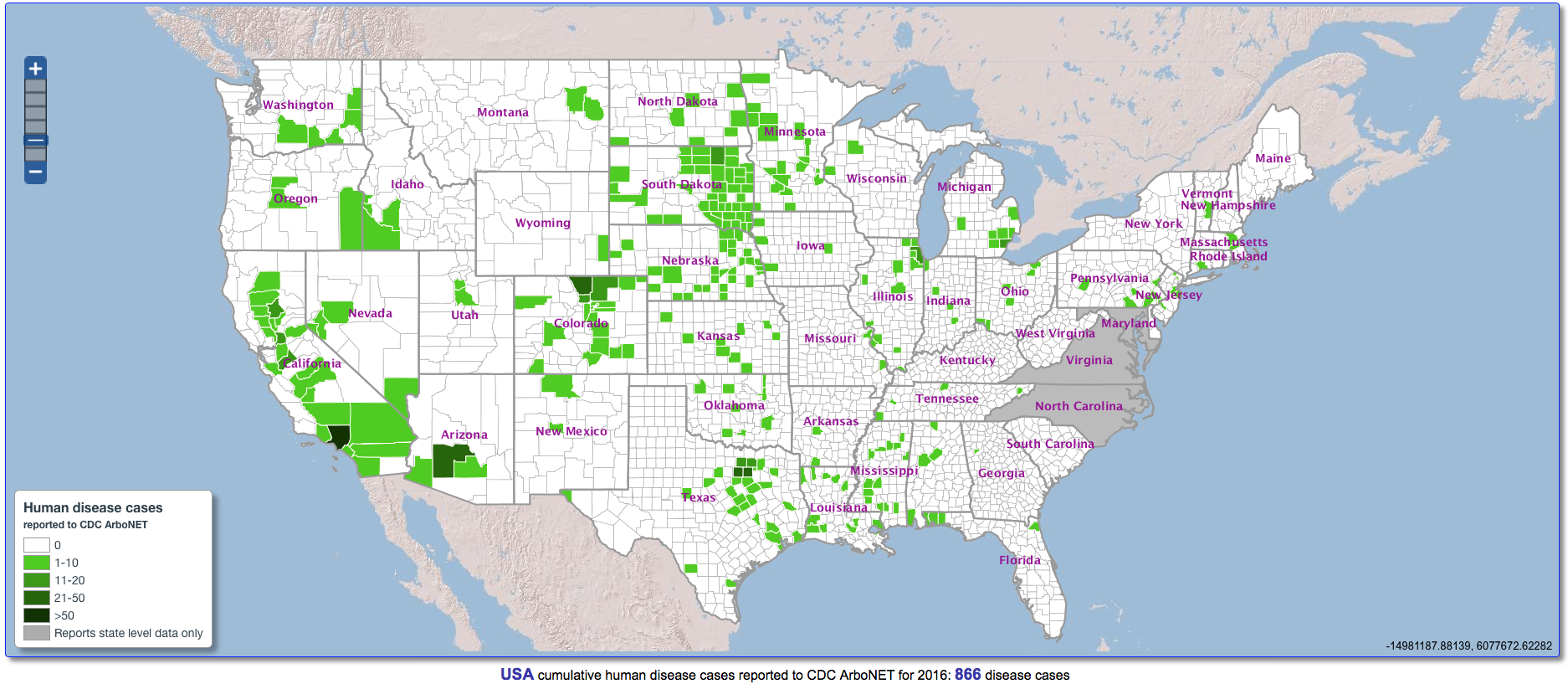

If you spent any time last summer swatting at mosquitoes during a backyard BBQ, you probably saw the headlines. There’s something about a "virus map" that makes everyone lean in, usually with a mix of anxiety and skepticism. We saw the West Nile virus map 2024 updates rolling out in real-time, and honestly, the data told a bit of a Jekyll and Hyde story.

On one hand, the total number of cases across the U.S. actually dropped compared to the previous year. We went from over 2,400 cases in 2023 down to about 1,466 cases in 2024. You might think, "Cool, it's going away." But that’s exactly what most people get wrong. While the raw numbers were lower, the intensity in specific hotspots was brutal.

Where the Map Was "Glowing" Red

When you look at the final 2024 data, the map doesn't look like a uniform wash of color. It looks like a scatter plot of high-danger zones. Texas basically lived at the top of the leaderboard all year. They reported around 176 cases, with heavy concentrations around Dallas and Houston.

California and New York followed close behind. In New York alone, the state reported nearly 100 human cases, which is a lot when you consider how many "mosquito pools" (the batches of bugs the state tests) came back positive—over 2,100 of them in NYC and the surrounding counties.

Here is the thing about those maps you see on the news: they only show the people who got sick enough to see a doctor. Most experts, like those at the CDC, estimate that for every one case on that map, there are likely 80 other people who had the virus and never even knew it.

2024 Case Distribution (The Heavy Hitters)

Instead of a fancy table, let's just look at the raw reality of where the virus hit hardest last year:

- Texas: 176 cases (The national epicenter for 2024)

- California: 123 cases (High activity in the Central Valley and LA)

- New York: 98 cases (Significant urban spread)

- Nebraska: 92 cases (A massive spike for a smaller population)

- Colorado: 76 cases (Particularly in the Front Range)

The "Neuroinvasive" Reality

There is a word you'll see on the West Nile virus map 2024 legend that sounds like a sci-fi horror movie: neuroinvasive.

👉 See also: Saint Clare's Dover Hospital: What You Actually Need to Know About Emergency Care in Morris County

Basically, this means the virus didn't just give you a fever; it crossed the blood-brain barrier. In 2024, a staggering 72% of reported cases were classified as neuroinvasive. This is a bit of a statistical trap, though. The reason the percentage is so high isn't that the virus is getting "meaner." It’s that people with "West Nile Fever" (the milder version) usually just stay home, drink Gatorade, and never get tested.

The people who end up on the map are the ones with meningitis or encephalitis. We’re talking about high fevers, stiff necks, and that terrifying "brain fog" that’s actually brain inflammation. In 2024, about 10% of these severe cases were fatal.

Why 2024 Was Different (The Bird Connection)

You’ve probably heard that mosquitoes get the virus from birds. In 2024, we saw some weird stuff. Barbados, of all places, reported its first-ever human case in a child. Why? Migratory birds.

Even in the U.S., the 2024 map was shaped by local bird populations. In California, they tracked over 150 dead birds that tested positive. When the birds are dying, the mosquitoes are "hot." When the mosquitoes are hot, the humans are next. It’s a simple, albeit grim, chain reaction.

Is Climate Change Actually Making the Map Grow?

Kinda. It’s not just about "hotter" weather; it’s about weird weather.

The EPA and CDC have been tracking this for two decades. Warmer winters mean the Culex mosquitoes (the ones that carry West Nile) don't die off. They start breeding earlier. In 2024, we saw cases popping up as early as May and June, lingering well into a warm October.

Also, heavy rains followed by droughts create the perfect "nursery" for these bugs. Stagnant water in a dried-up drainage ditch is basically a 5-star resort for a mosquito looking to lay eggs.

What You Should Actually Do (Beyond the Map)

Looking at a map is great for awareness, but it doesn't keep you from getting bit. Since there is no vaccine for West Nile in humans (though there is one for horses, ironically), you’re the only line of defense.

- Check your "DEET" levels. Honestly, the "natural" stuff usually doesn't cut it when the virus is active. Use EPA-registered repellents with DEET, Picaridin, or IR3535.

- The "Dusk and Dawn" rule is real. Culex mosquitoes are most active when the sun is low. If you’re hiking or gardening then, wear long sleeves.

- The "One Cup" Rule. It only takes a bottle cap full of water for a mosquito to breed. Walk around your yard once a week. Flip the kids' toys, clean the birdbath, and check the gutters.

If you do get sick and notice a high fever or a "worst headache of your life" situation, don't just tough it out. Tell your doctor you’ve been around mosquitoes. They can't "cure" the virus with an antibiotic—it's a virus, after all—but they can provide the supportive care (IV fluids, etc.) that keeps a neuroinvasive case from becoming a statistic.

Next Step: You should walk around your property today and identify at least three spots where water might collect after the next rain, such as clogged gutters or flowerpot saucers, and clear them out to disrupt the local breeding cycle.