Everyone knows the skip. You can’t even think about the we're off to see the wizard song without imagining Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion linked arm-in-arm, bouncing down a yellow brick road. It's iconic. But honestly, it’s also one of the weirdest pieces of music history because it’s basically a glorified commercial for a plot point. It works because it has to.

When The Wizard of Oz hit theaters in 1939, nobody knew it would become the most-watched film in history. They just knew they had a massive budget and a lot of technical headaches with Technicolor. The music, composed by Harold Arlen with lyrics by E.Y. "Yip" Harburg, had a heavy burden. It needed to bridge the gap between a dusty, sepia-toned Kansas and a neon-green dreamscape. This song did that. It’s the literal engine of the movie.

The Secret Architecture of a 1930s Earworm

Let’s get technical for a second, but not too boring. The song’s actual title is "We’re Off to See the Wizard (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz)." Most people just call it the "Yellow Brick Road song" or something similar.

Harold Arlen was a genius of "American Songbook" structures. He didn't just write a jingle. He wrote a march. If you listen to the underlying rhythm, it’s a classic 4/4 march tempo. This was a deliberate choice. It keeps the pace of the movie moving. Without that driving beat, the scenes of them walking through the woods would feel like a slog. It gives the characters—and the audience—a sense of momentum.

Yip Harburg’s lyrics are deceptively simple. "Because, because, because, because, because!" It sounds like something a kid would say when they don't have a real answer. That’s the point. It’s whimsical. It’s nonsensical. But it also hits that psychological sweet spot of repetition that makes a song impossible to forget. Harburg was known for his socialist leanings and his love for the "common man," and you can see that in how he writes for these outcasts. They aren't singing about grand glory; they’re singing about a guy who can fix their problems. It’s a song of hope, even if it’s a bit repetitive.

Why the Vocals Sound So Distinctly Strange

Ever noticed how the voices in the we're off to see the wizard song sound a bit "off" compared to modern recordings? There's a reason for that. Recording technology in 1938 and 1939 was still relatively primitive compared to what came just a decade later.

They used a process called "pre-recording." The actors would record their vocals in a studio, and then they would lip-sync on the set. This is standard now, but back then, matching the energy of a physical dance routine with a studio vocal was tough. Judy Garland’s voice is, of course, a powerhouse. Even at sixteen, she had a vibrato that could shake a building. But listen to Bert Lahr (the Lion) or Jack Haley (the Tin Man). They’re using vaudeville-style vocal projections.

The "Munchkin" Influence

The song actually appears in several iterations. The most famous version is the one sung by the quartet, but it starts with the Munchkins. To get those high-pitched "Munchkin" voices, the engineers recorded the singers at a slow speed and then played the tape back at a normal speed. This shifted the pitch upward without changing the tempo too drastically. It was cutting-edge stuff for the time. When the main cast picks up the tune later, they carry that same "storybook" energy into the darker parts of the forest.

The Lyrics Nobody Remembers Correctly

We all think we know the words. "We're off to see the Wizard, the Wonderful Wizard of Oz." Easy. But then it gets into the "If ever, if ever a Wiz there was" part.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Most people trip over the phrasing there. It’s actually:

“If ever, if ever a Wiz there was, the Wizard of Oz is one because...”

It’s a circular logic loop. It doesn't actually explain why he's a wizard, just that he is one because he is one. It’s brilliant songwriting because it reflects the Oz experience. Everything in Oz is a bit of a facade. The song is praising a man that the characters haven't even met yet, based entirely on a reputation that turns out to be a total sham.

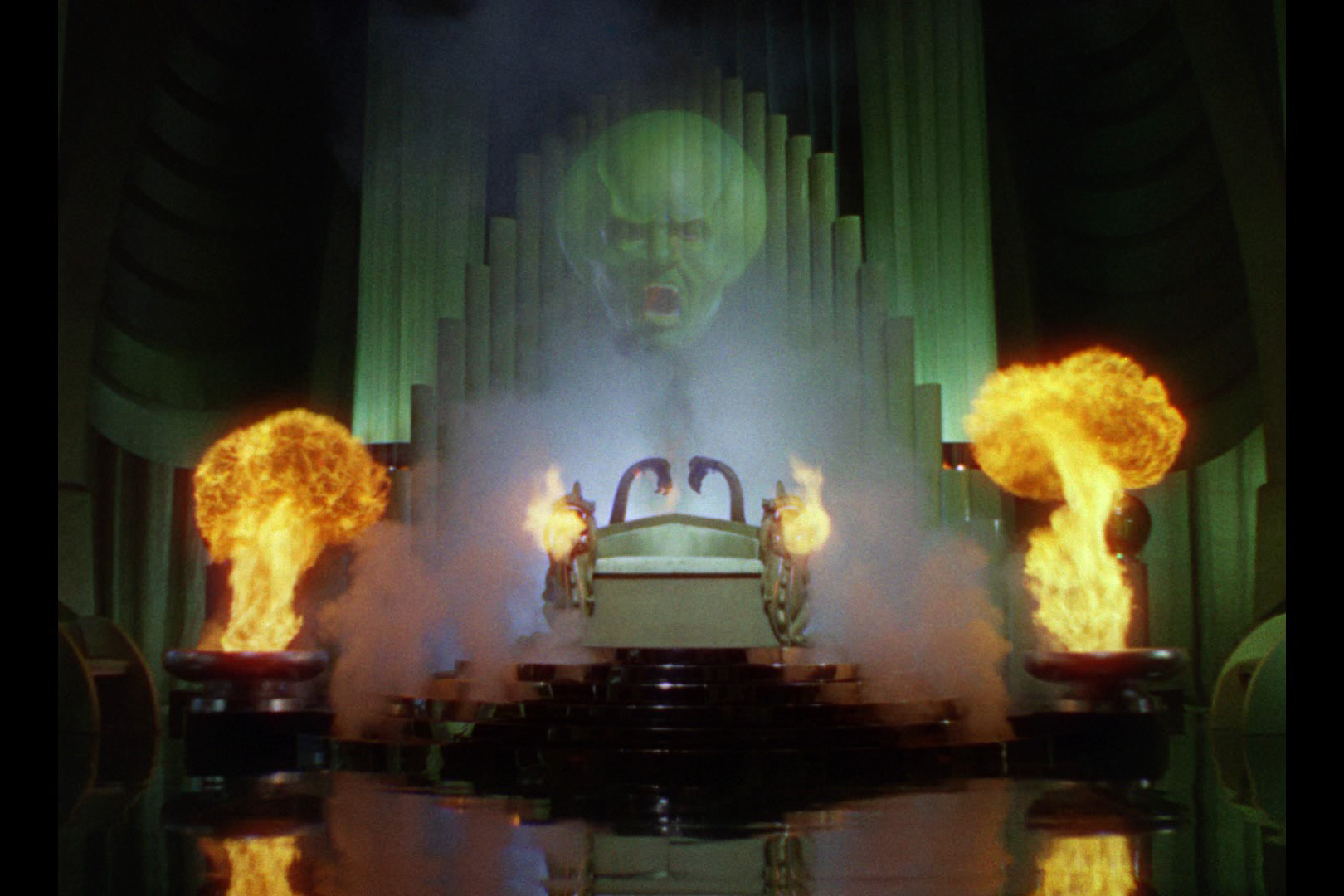

There's a layer of irony there that most kids miss. The song is a joyful celebration of a lie. The Wizard is just a guy behind a curtain with some smoke machines, but the song treats him like a deity.

The Cultural Shadow of the Yellow Brick Road

You can't escape this song. It’s been sampled, parodied, and referenced in everything from The Simpsons to high-end fashion shows. Why? Because it represents the "Quest."

In storytelling, the "Quest" is a foundational trope. The we're off to see the wizard song is the ultimate anthem for anyone who is looking for something they think they lack. Dorothy wants home, the Scarecrow wants a brain, the Tin Man wants a heart, and the Lion wants courage. The irony, which the song subtly reinforces by being so high-energy and brave, is that they already have these things. They’re walking miles and singing songs to find what’s already inside them.

Musically, it’s been covered by everyone from Anne Murray to Alvin and the Chipmunks. But nobody touches the original. There’s a certain "crackling" quality to the 1939 recording—a mix of the orchestral swell and the slight hiss of the master tapes—that creates a sense of nostalgia that modern digital recordings can't replicate.

Production Nightmares Behind the Music

The making of The Wizard of Oz was a disaster. We've heard the stories. Buddy Ebsen (the original Tin Man) almost died from the aluminum powder makeup. Margaret Hamilton (the Witch) got severely burned. Judy Garland was being pushed to her breaking point.

When you hear them singing "We're off to see the Wizard," you're hearing actors who were often exhausted, working under hot lights in heavy costumes. Ray Bolger’s Scarecrow mask left permanent lines on his face. Jack Haley’s Tin Man suit was so stiff he had to lean against a board to rest because he couldn't sit down.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

Yet, the song sounds effortless. That’s the magic of Hollywood’s Golden Age. The contrast between the grueling reality of the set and the pure, sugary joy of the music is staggering. It’s a testament to Herbert Stothart’s underscores and Arlen’s composition that the stress of the production doesn't bleed into the audio.

Impact on the American Songbook

The Library of Congress doesn't just archive anything. They archive things with "cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance." This song—and the entire soundtrack—is etched into the National Recording Registry.

It changed how movie musicals were structured. Before Oz, many film musicals were "backstage musicals," where the characters were performers putting on a show. The Wizard of Oz helped popularize the "integrated musical," where characters sing because their emotions are too big for words. When they sing about the Wizard, they aren't performing for an audience; they’re motivating themselves. It changed the grammar of cinema.

Semantic Variations and Why They Matter

When people search for this, they often look for "Wizard of Oz marching song" or "Follow the Yellow Brick Road lyrics." All these pieces connect back to the same 1939 sessions. It's a cohesive musical ecosystem. Even the instrumental snippets played by the orchestra throughout the film are just variations on this one melody. It’s the "motif" of the entire journey.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Song

A common misconception is that this song was the "big hit" of the movie. It wasn't. "Over the Rainbow" was the breakout star. In fact, "Over the Rainbow" almost got cut from the movie because MGM executives thought it slowed down the pace too much.

The we're off to see the wizard song was seen as the "utility" song. It was the "workhorse." It’s the one that did the heavy lifting to keep the plot moving. While "Over the Rainbow" is a ballad about yearning, this song is about action. You need both to make a masterpiece. One provides the soul, the other provides the heartbeat.

Another myth is that the lyrics were just filler. Harburg was actually very meticulous. He wanted the song to feel like a "round." If you listen closely, the way the voices enter and exit mimics a campfire song. It’s designed to be communal. It’s the first time in the movie that these disparate characters truly bond.

Practical Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you're a fan of the music, there are a few things you should actually look for. Don't just settle for a generic streaming version.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

- Search for the 1995 Rhino Records Deluxe Edition: This is widely considered the best-engineered version of the soundtrack. It includes outtakes and "extended" versions of the songs that were trimmed for the final film.

- Listen for the "Ghost" Vocals: In some of the choral sections of the Munchkinland sequence, you can hear the layering of professional singers (like the Ken Darby Singers) over the actors. It creates a rich, "wall of sound" effect that was very sophisticated for 1939.

- Check the Sheet Music: Original 1939 sheet music for this song is a major collector's item. Look for the "Big 3" publishing logo (Feist, Miller, Robbins).

How to Experience the Song Today

To really appreciate the we're off to see the wizard song, you have to watch it in context with the 4K restoration of the film. The audio has been cleaned up using modern de-hissing tech that preserves the dynamic range without making it sound "sterile."

You can hear the clinking of the Tin Man’s suit and the thud of Dorothy’s ruby slippers on the stage floor. It grounds the fantasy in a physical reality.

Actionable Steps for the Ultimate Experience:

- Compare the Versions: Listen to the "Munchkin" version and the "Quartet" version back-to-back. Notice how the orchestration gets "thicker" and more brass-heavy as the characters get closer to the Emerald City.

- Analyze the Lyrics: Look at the wordplay. Harburg uses internal rhyme (Wiz/is/was) to create a rhythmic "trip-up" that mirrors the physical skipping the actors are doing.

- Study the Choreography: Watch the scene on mute. The song's rhythm is so strong that you can actually "hear" it just by watching the actors' feet. That is the hallmark of a perfectly written march.

The song isn't just a piece of nostalgia; it’s a masterclass in functional songwriting. It’s short, it’s punchy, and it tells you exactly what you need to know: the journey is hard, but as long as we’re singing, we’re moving forward. It’s basically the 1939 version of a "get hyped" playlist.

Next time it gets stuck in your head, don't fight it. Just realize you're participating in a century-old tradition of American musical excellence. There's a reason we're still singing it nearly ninety years later. It’s because, because, because, because, because—it’s just a damn good song.

To dive deeper, look into the Harold Arlen archives or check out the "Making of" documentaries on the latest Blu-ray releases. There are hours of studio session recordings that show just how much work went into those few minutes of "simple" film music.

---