You’re standing on your porch. The sky looks like a bruised plum—dark, heavy, and weirdly silent. You pull out your phone, open a map, and see a blob of red heading straight for your house. But here’s the thing: that little pixelated "rain" on your screen isn't just a drawing. It’s the result of a massive dish in a dome miles away firing electromagnetic pulses into the atmosphere at the speed of light.

Most people use weather radar en vivo just to see if they need an umbrella for the walk to the car. Honestly, that’s barely scratching the surface of what’s actually happening in the sky. If you only look at the colors, you're missing the "velocity" data that tells you if a tornado is literally forming over your neighborhood before the sirens even start wailing.

It's about survival, sure. But it's also about understanding the sheer physics of our atmosphere in real-time.

The Lag Reality: Is "En Vivo" Actually Live?

Let's get one thing straight. "Live" is a bit of a lie in the meteorology world. When you’re looking at weather radar en vivo, you are almost always looking at data that is between five and ten minutes old. Why? Because the radar dish has to complete a full 360-degree rotation at multiple tilt angles to create a "volume scan."

The National Weather Service (NWS) uses the WSR-88D system, better known as NEXRAD. These stations tilt. They spin. They send data to a central hub. Then, your app has to download that data and render it. By the time that red "hook echo" shows up on your screen, the storm has already moved a mile or two.

During severe weather, the NWS uses something called SAILS (Supplemental Adaptive Intra-Cloud Low-Level Scan). It basically tells the radar to stop being so thorough with the upper atmosphere and just scan the bottom layer more often because that's where the damage happens. Even then, you’re dealing with a delay. If you see a purple core on your screen, that hail is likely already hitting someone's windshield.

It’s a bit like watching a star through a telescope; you’re seeing the past, just a very recent version of it.

Why Your App Looks Different Than the Local News

Have you ever noticed that The Weather Channel app shows light green rain, but the local news guy is screaming about a "debris ball" in the same spot? It’s because of smoothing.

Most consumer-grade apps use "smoothing" algorithms to make the radar look pretty and fluid. They essentially guess what happens between the data points to make the transitions look like a movie. Professional meteorologists hate this. Smoothing hides the "noise" that actually tells you what a storm is doing.

Real weather radar en vivo is grainy. It’s blocky. Those blocks are called "bins," and they represent the actual resolution of the radar beam. If you want the truth, you look at the raw data.

👉 See also: Berkeley Computer Science Courses: Why the EECS Grind is Still Different

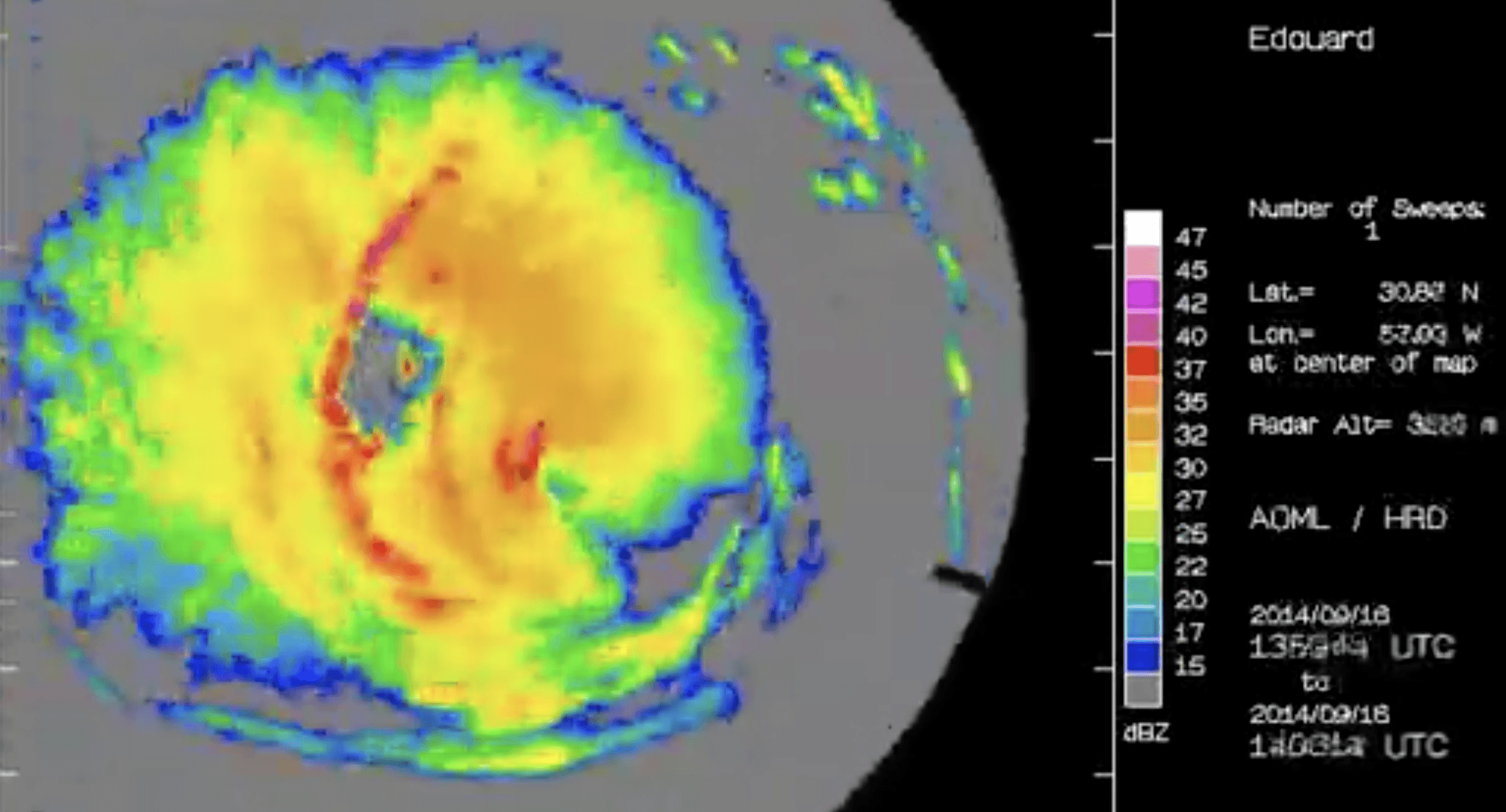

Reflectivity is what most of us know—the green, yellow, and red stuff. It measures how much energy bounced back to the radar. But "Base Velocity" is where the real magic is. It shows which way the wind is blowing. If you see bright green (moving toward the radar) right next to bright red (moving away), you have rotation. That’s a couplet. That’s where the tornado lives.

The Mystery of "Ghost" Rain and Wind Farms

Ever opened your radar app on a perfectly clear day and seen a weird circle of blue or green around the radar station? You’d think a storm was brewing out of nowhere. It’s not.

This is usually "ground clutter" or "anomalous propagation." Basically, the radar beam hits something it wasn't supposed to—like a swarm of bats, a flock of birds, or even a localized temperature inversion that bends the beam back toward the ground.

- Biologicals: Every evening in south-central Texas, the radar picks up millions of Mexican free-tailed bats emerging from caves. It looks like a massive rainstorm.

- Wind Farms: Those giant turbines in Kansas or West Texas? They reflect radar signals like crazy. They create "flashing" spots on the map that can drive a novice weather watcher insane.

- Sun Spikes: At sunrise and sunset, the radar might pick up the sun's own electromagnetic radiation, showing a straight line of "noise" pointing directly at the horizon.

Dual-Pol: The Game Changer Nobody Noticed

About a decade ago, the US finished upgrading the NEXRAD network to "Dual-Polarization." Before this, radars only sent out horizontal pulses. Imagine a flat pancake of energy. It could tell how wide a raindrop was, but not how tall it was.

Now, radars send both horizontal and vertical pulses. It's like the difference between seeing a 2D silhouette and a 3D model.

✨ Don't miss: Verizon Wireless Port In Number: What Usually Goes Wrong and How to Fix It

This changed everything for weather radar en vivo. Now, we have "Correlation Coefficient" (CC). This is a fancy term for "is everything in this area the same shape?" Raindrops are all roughly the same shape. But if a tornado rips through a town and throws pieces of a 2x4, a recliner, and some pink insulation into the air, the CC value drops through the floor.

When a meteorologist sees a "Tornado Debris Signature" (TDS) on the CC map, they don't need a spotter on the ground to confirm a tornado. They are literally seeing the wreckage of people's lives in the air. It’s the most sobering thing you can see on a screen.

Beyond the Screen: How to Use Radar Like a Pro

If you really want to stay safe, stop using the default "future cast" settings. These are just computer models guessing. Stick to the "Base Reflectivity" and "Base Velocity" views.

Watch for the "Inflow Notch." This is a little bite taken out of the side of a storm. It’s where the storm is "breathing," sucking in warm, moist air to fuel its engine. If you see a notch, the storm is healthy and likely intensifying.

Also, pay attention to the distance from the radar site. Radar beams travel in a straight line, but the Earth is curved. The further away a storm is, the "higher up" the radar is looking. If a storm is 100 miles away, the radar might be looking at the top of the clouds, 15,000 feet in the air. It could be pouring at the ground, but the radar won't show it because the beam is literally shooting over the top of the rain. This is why "radar holes" exist in rural areas.

📖 Related: Installing a No C Wire Smart Thermostat: What Actually Works (And Why Some Systems Fail)

Actionable Steps for Your Next Storm

Don't just stare at the pretty colors. When the sirens go off or the sky turns that weird shade of green, take these specific steps with your weather radar en vivo tools:

- Check the Timestamp: Always look at the bottom of the map to see exactly when the data was captured. If it’s more than 8 minutes old, the storm is significantly further along than the map shows.

- Find Your Radar Site: Know where the nearest NWS radar station is (e.g., KTLX in Oklahoma City or KOKX in New York). The closer you are to the station, the more accurate the low-level data will be.

- Toggle to Velocity: If there’s a severe thunderstorm warning, switch from "Reflectivity" to "Velocity." Look for "bright" colors side-by-side. That is where the wind is most violent.

- Ignore the "Future" Map: Those 1-hour projections are rarely right once a storm becomes "outflow-dominant" or starts to "cycle." Watch the loop of the last 30 minutes instead; your brain is better at projecting that motion than a basic app algorithm.

- Identify the "Hail Core": Look for the "white" or "bright purple" centers within the red areas. That’s usually where the largest hail is falling. If that’s moving toward your car, get it under a sturdy roof immediately.

The atmosphere is a chaotic, fluid beast. Using weather radar en vivo gives us a window into that chaos, but only if we know how to look through it. The next time the sky turns dark, remember that you’re looking at a 3D scan of a massive energy system, not just a map with some paint on it. Stay weather-aware, stay skeptical of "smoothed" data, and always have a backup way to get warnings that doesn't rely on your cell signal.