If you’ve ever complained about a rainy Monday or a particularly nasty thunderstorm, honestly, count your blessings. On Earth, weather is basically a gentle dance of water vapor driven by a sun that’s relatively close. But when we talk about weather in jupiter planet, we are stepping into a realm of pure, unadulterated atmospheric chaos.

Jupiter doesn't have a "surface" in the way we understand it. You can't land a plane there. You can't stand on a rock and watch the clouds go by. Instead, the "weather" is essentially the entire planet. It’s a 43,000-mile-deep ocean of hydrogen and helium that gets thicker, hotter, and more violent the further down you go.

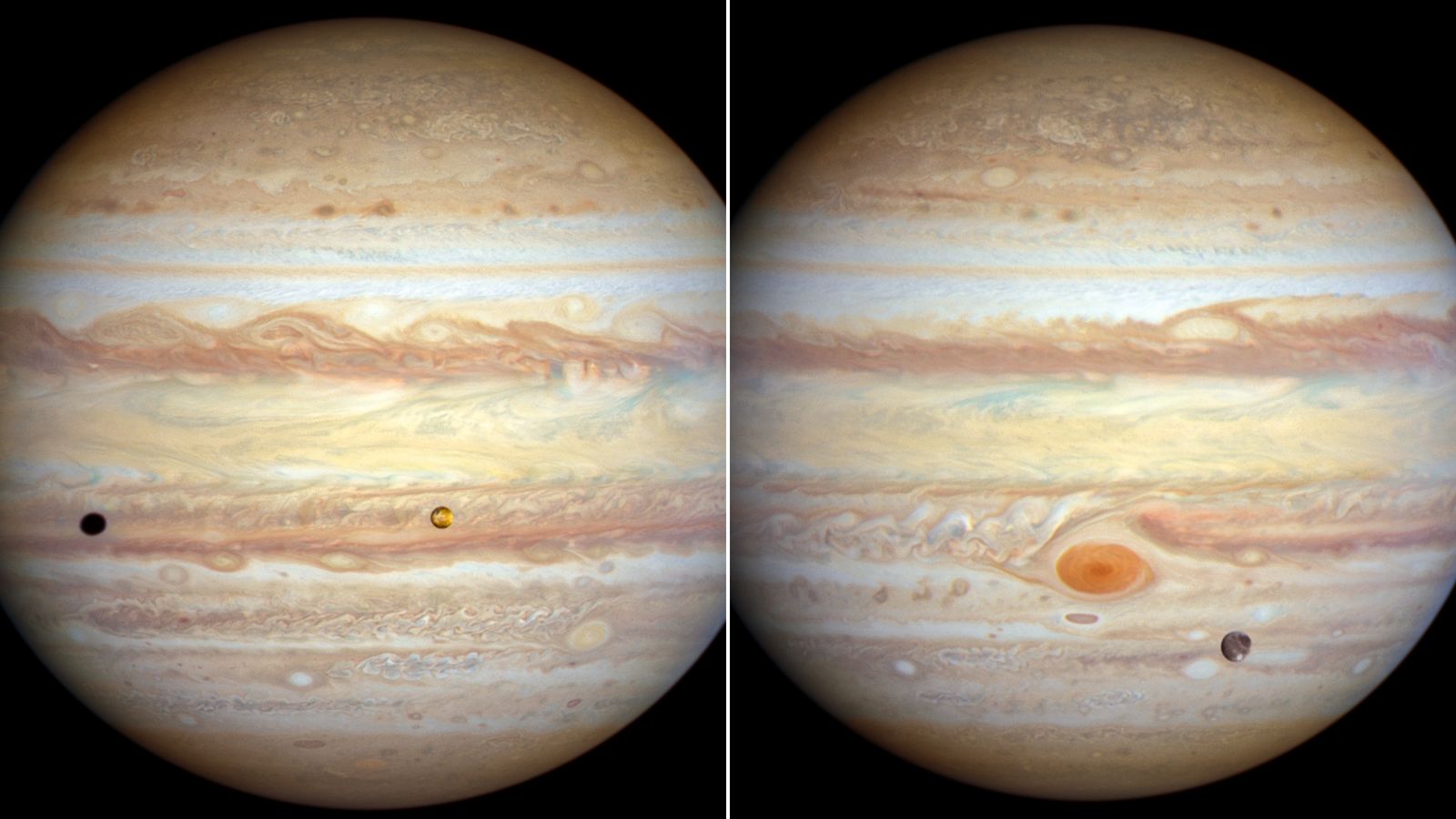

The Great Red Spot: A Storm That Could Eat Earth

Most of us know about the Great Red Spot. It’s the celebrity of Jovian weather. But here is what most people get wrong: they think of it as a hurricane. While it looks like one, it’s actually an anticyclone.

Basically, instead of air rushing into a low-pressure center, this massive beast is a high-pressure system. It rotates counterclockwise in the southern hemisphere. It’s been raging for at least 190 years—and quite possibly over 350 years if it's the same spot Gian Domenico Cassini saw in the 1600s.

Is the Spot Dying?

Lately, things have been getting weird. Recent data from the Hubble Space Telescope and NASA’s Juno mission show that the spot is shrinking. It used to be big enough to fit three Earths inside. Now? You’d be lucky to squeeze one and a third Earths into its borders.

👉 See also: When Were Clocks First Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Time

- Shrinkage Rate: It’s getting smaller by about 580 miles per year.

- Shape Shifting: It’s moving from an oval shape to a more circular one.

- Flaking: In 2019, astronomers saw "flakes" of the storm breaking off and spinning away.

Despite this, it's not exactly "weak." Winds at the edge of the spot still scream at speeds up to 432 kilometers per hour. That’s faster than any Category 5 hurricane ever recorded on our home turf.

Ammonia Mushballs and Shallow Lightning

One of the most mind-blowing discoveries from the Juno mission involves what scientists call "mushballs." On Earth, we have hail. On Jupiter, you have slushy, ammonia-water ice balls. These things form about 40 miles below the cloud tops. Powerful updrafts loft water ice high into the atmosphere where it meets ammonia vapor. The ammonia acts like antifreeze, melting the ice into a slushy mess.

These mushballs get heavy and fall deep into the atmosphere, dragging ammonia with them. This is why scientists were so confused for years about why ammonia seemed to be missing from the upper layers of Jupiter’s atmosphere—it’s literally being rained out in the form of softballs-sized slush.

And then there’s the lightning.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

Jovian lightning is terrifying. On Earth, lightning comes from water clouds. On Jupiter, Juno detected "shallow lightning" that originates in clouds of ammonia and water. It’s a constant, flickering strobe light of electrical energy that can be 1,000 times more powerful than what we see in a summer storm.

The Winds That Never Stop

Jupiter’s appearance—those beautiful, coffee-and-cream colored stripes—is actually a map of its wind. These are called belts (the dark ones) and zones (the light ones).

They move in opposite directions. This creates immense friction at the borders, which is exactly where the smaller cyclones and white ovals tend to pop up.

- Equatorial Jets: Winds at the equator can reach 540 kilometers per hour.

- Polar Cyclones: At the North Pole, there’s a central cyclone surrounded by eight smaller "groupie" cyclones. They bounce off each other like bumper cars but never merge.

- Stratospheric Beasts: In 2021, using the ALMA telescope, researchers found winds near the poles traveling at 1,450 kilometers per hour in the stratosphere.

What’s wild is that this weather isn't just solar-powered. Jupiter is actually five times further from the Sun than Earth is. Sunlight there is weak. Instead, the weather in jupiter planet is driven by the planet's own internal heat. Jupiter radiates about 1.5 to 2 times more heat than it receives from the Sun. It’s essentially a giant engine cooling down from its violent birth 4.5 billion years ago.

🔗 Read more: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

The Mystery of the Deep Atmosphere

For a long time, we didn't know if these winds were just a thin skin on the surface. We now know, thanks to gravity measurements, that these jet streams actually extend about 3,000 kilometers (1,800 miles) down.

At that depth, the pressure is so high that the gas starts to act like a liquid metal. It becomes "dragged" by Jupiter’s magnetic field, finally slowing the winds down.

How You Can See Jupiter’s Weather Yourself

You don't need a billion-dollar probe to see this chaos.

- Get a telescope: Even a basic 4-inch (100mm) telescope will show you the two main equatorial belts.

- Look for the Spot: Use an app like Sky Tonight to find when the Great Red Spot is facing Earth. It rotates with the planet every 10 hours, so timing is everything.

- Watch the Moons: You’ll often see the shadows of Io or Europa crossing the cloud tops. These "transits" look like tiny black ink spots on the planet's face.

If you’re interested in tracking the latest from the Juno mission, NASA frequently releases raw data for "citizen scientists" to process. You can actually go to the JunoCam website, download the latest images, and use Photoshop to bring out the colors of the polar cyclones yourself.

Jupiter is currently heading toward its next opposition, which means it will be at its brightest and closest to Earth. This is the best time to grab some binoculars or a telescope and look up. You aren't just looking at a planet; you’re looking at a 4.5-billion-year-old storm that shows no signs of quieting down.

Stay curious, and maybe keep an umbrella handy—just in case those ammonia mushballs ever find a way to Earth. (Kidding, they won’t. But it’s a cool thought.)