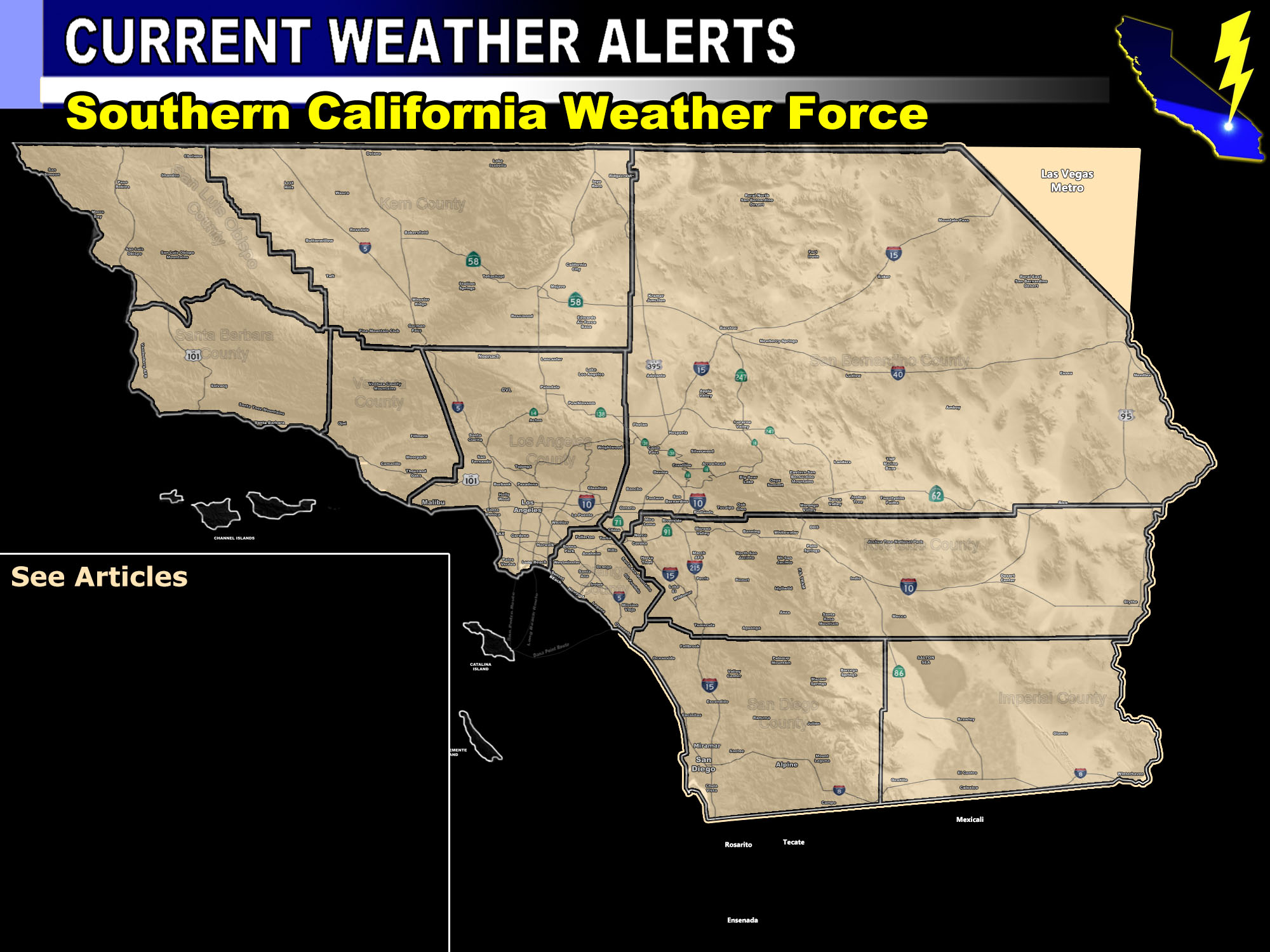

You’re staring at your phone. The little blue dot says you're standing in a downpour, but you look outside and the pavement is bone dry. Or worse, you're driving through a "moderate" green blob on the map and suddenly hit a wall of water so thick you can’t see your own hood. Southern California weather is weird. It’s not just the microclimates or the way the Santa Anas scream through the canyons. The real culprit behind your confusion is often how we interpret weather doppler Southern California data—and the massive "blind spots" that even the most expensive government tech can't quite fix.

Rain here isn't like rain in the Midwest. Out there, storms are massive, flat, and predictable. In SoCal, the terrain is basically a giant obstacle course for radar beams. If you've ever wondered why the National Weather Service (NWS) seems to miss that sudden cell over Lake Elsinore or why the "atmospheric river" looked way scarier on the news than it did in your backyard, you’ve hit on the fundamental limitation of radar technology in a mountainous desert.

The Beam Overshooting Problem

Radar works on a simple premise: send out a pulse, hit a drop of water, and see how much energy bounces back. But here’s the kicker. Radar beams travel in straight lines, while the Earth is curved. To make matters worse, the NWS Nexrad stations (the big white soccer balls on hills) are often placed on high peaks to see over things.

Take the KSOX radar in Santa Ana Mountains or KVTX in Los Angeles. Because they sit so high up, the beam often shoots right over the top of low-level clouds. In Southern California, a lot of our "Grey May" or winter drizzle happens in the bottom few thousand feet of the atmosphere. The radar is literally looking over the rain's head. You see a clear map on your app, but you're getting soaked. Honestly, it’s frustrating. You’re looking at a "clear" scan while turning on your windshield wipers.

Then there's the "beam blocking" issue. We have mountains everywhere. The San Gabriels, the San Bernardinos, the Santa Monicas. If a storm cell is tucked behind a 10,000-foot peak, the radar beam hits the dirt and stops. We call these radar shadows. If you live in a valley shadowed by a range, you’re basically living in a data black hole. Forecasters have to use "composite" images, stitching together data from different sites to try and peek around the corners, but it’s never a perfect 1:1 representation of what’s hitting your roof.

🔗 Read more: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

Why Dual-Pol Changed the Game (Sorta)

About a decade ago, the NWS finished upgrading most of the weather doppler Southern California infrastructure to "Dual-Polarization" radar. Before this, radar only sent out horizontal pulses. It could tell you how wide a raindrop was. Dual-Pol sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses.

This was a massive deal for us. Why? Because it allows meteorologists to tell the difference between a heavy raindrop, a snowflake, and a piece of burning pine needle. During wildfire season, this is literally a lifesaver. When the Getty Fire or the Thomas Fire was ripping, the radar could "see" the smoke plume and the debris being lofted into the air. By looking at the "Correlation Coefficient" (a fancy metric for how similar the shapes in the air are), experts can tell if they're looking at a cloud or a literal rain of ash.

But it’s not just for fires. In our rare Southern California snow events—think the Grapevine or the Cajon Pass—Dual-Pol helps determine the "melting layer." It tells us exactly where the rain is turning to slush. If you’re trying to decide whether to haul a trailer over the pass, that’s the data that matters, not just the "green blob" on a generic weather app.

The Local Heroes: X-Band Radars

Because the big government Nexrad stations have those "blind spots" I mentioned, Southern California has started seeing the rollout of smaller, "short-range" radars called X-Band. These are the scrappy underdogs of the weather world. They don't have the 200-mile range of the big guys, but they sit lower to the ground.

💡 You might also like: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

The University of Massachusetts Amherst and various local agencies have experimented with these in the LA basin. They fill in the gaps. They see the low-level "shallow" rain that the high-mountain radars miss. If you ever see a weather map that looks incredibly high-resolution—almost like you can see individual streets getting rained on—you’re likely looking at integrated X-Band data. It’s the difference between a blurry VHS tape and a 4K stream.

High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) vs. Real-Time Doppler

People often confuse "The Radar" with "The Forecast." When you look at an app and see the rain moving over the next two hours, that’s not radar. That’s a model. Specifically, it’s usually the HRRR (High-Resolution Rapid Refresh) model.

The actual weather doppler Southern California data is what happened about 5 to 10 minutes ago. It takes time for the dish to spin, the data to be processed, and the image to be uploaded to the server. By the time you see that "hook echo" or that heavy red cell on your screen, it has already moved. In a place like the Inland Empire, where summer monsoons can pop up and vanish in twenty minutes, the delay is everything.

You have to learn to "extrapolate." Look at the direction of the wind. If the cell is moving at 20 mph and the scan is 6 minutes old, that cell is already two miles further than where the icon is sitting. It sounds like a lot of work, but in a flash flood situation in the canyons, those two miles are the difference between a safe drive and a swift-water rescue.

📖 Related: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

The Myth of the "Rain Shadow" on Radar

I hear this all the time: "The radar showed it was going to pour in Palm Springs, but it just stopped at the mountains!"

That’s not a radar glitch. That’s the "Orographic Effect." As moisture-heavy air hits the Santa Ana or San Jacinto mountains, it’s forced upward. It cools, condenses, and dumps all its water on the "windward" side (like Orange County or the coastal slopes). By the time the air gets over the peak and down into the desert, it’s dry.

The radar beam, however, might still be seeing moisture high up in the clouds as they pass over the peak. It looks like "rain" on the map, but the water is evaporating before it hits the desert floor. This is called virga. It’s the ghost of rain. You see it as streaks coming off the clouds that never touch the ground. Your app says "Heavy Rain," but you’re standing in 90-degree heat with a dry face.

How to Actually Use This Info

If you want to be a local pro, stop using the default "weather" app that came with your phone. Those apps usually scrape data from the cheapest available source and use "smoothing" algorithms that make the data look pretty but inaccurate.

- Use the NWS Enhanced Data Display (EDD): It’s clunky, but it gives you the raw feed.

- Look for "Base Reflectivity" vs. "Composite": If you want to know what’s hitting the ground now, look at Base Reflectivity at the lowest angle ($0.5^\circ$).

- Check the "Velocity" scan: If you're worried about high winds or a rare SoCal tornado (yes, they happen), the Velocity tab shows you which way the wind is blowing inside the storm. If you see bright green next to bright red, that’s rotation. Get inside.

- Watch the "Loop": Never look at a static image. A single frame is useless. You need the loop to see the "trend." Is the storm intensifying (getting redder) or collapsing?

Southern California's geography makes it one of the hardest places in the country to provide 100% accurate radar coverage. Between the 10,000-foot peaks and the curvature of the coast, there will always be surprises. But if you understand that the "soccer ball" on the mountain is looking over the drizzle and getting blocked by the hills, you'll stop being surprised when you get wet.

Next time a big winter storm rolls in from the Pacific, check the radar sites at Vandenberg (KVBX), Edwards AFB (KEYX), and San Diego (KNKX). By toggling between these three, you can usually piece together a much more accurate picture of the incoming front than any automated "AI weather assistant" will ever give you. Know the limitations of the beam, and you'll never be caught without an umbrella again.

Actionable Steps for the Next Storm

- Download a dedicated radar app: Look for ones like RadarScope or Carrot Weather that allow you to select specific NWS stations (KSOX, KVTX, KNKX).

- Identify your local "Shadow": Figure out which mountain range sits between you and the nearest radar station. If there's a big one, know that your radar readings will always be slightly underestimated.

- Compare "Reflectivity" with "Correlation Coefficient": During fire season, if you see a "storm" popping up over a burn scar, check the CC map. If the values are low, that's not rain—it's a debris ball or smoke, and you should check for evacuation orders immediately.

- Trust your eyes over the app: If the clouds look "bulgy" and dark (mammatus or cumulonimbus) but the radar is clear, trust the sky. The radar is likely overshooting the cell.