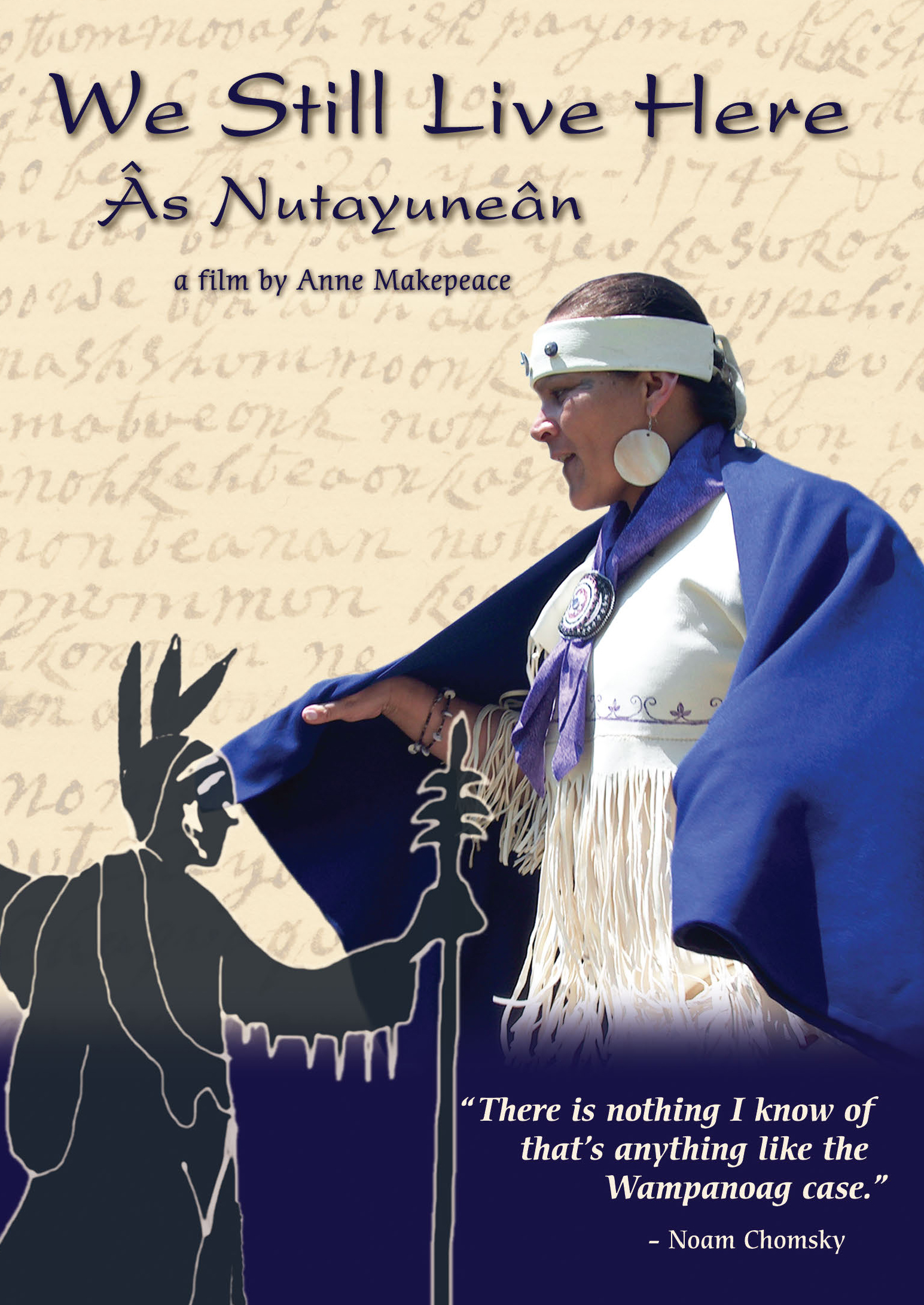

Language isn't just a bunch of words or a way to ask where the bathroom is. It's an entire universe. When a language disappears, that universe collapses. For a long time, people thought the Wampanoag language—the tongue spoken by the People of the First Light in what we now call Southeastern Massachusetts—was gone for good. They were wrong. The documentary We Still Live Here (Âs Nutayuneân) told a story that many outsiders found impossible, but for the Wampanoag, it was a homecoming centuries in the making.

It’s been years since Anne Makepeace’s film first hit the festival circuit and PBS, yet the ripples are still felt today. You see, this wasn't just a movie about history. It was a blueprint.

The project started with a dream. Literally. Jessie Little Doe Baird, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, began having recurring dreams where her ancestors spoke to her in a language she didn't understand. It’s the kind of story that sounds like Hollywood fiction, but the results are documented, academic, and physically alive in the children speaking Wôpanâak today.

Honestly, the sheer audacity of the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project (WLRP) is what keeps it relevant. They decided to bring back a language that hadn't been spoken fluently for over 150 years. No native speakers were left. None. Think about the mountain they had to climb.

The Technical Miracle of Wôpanâak

How do you find a voice that has been silent for six generations? You look at the archives. Ironically, the tools of colonization became the keys to liberation. Because the English were so intent on converting the Wampanoag to Christianity, they translated the Bible into Wôpanâak in 1663. This became the first Bible printed in the Western Hemisphere.

John Eliot, a Puritan missionary, worked with native speakers to create a written version of the language using the Roman alphabet. Because of this, the Wampanoag became highly literate. They wrote deeds. They wrote letters. They wrote petitions to the government.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Jessie Little Doe Baird didn't just "guess" how the language worked. She went to MIT. She worked with the late linguist Kenneth Hale. Together, they looked at the massive trove of 17th-century documents. They used Algonquian linguistic patterns from related languages—like Passamaquoddy or Mik’maq—to fill in the blanks. It was like a 10,000-piece jigsaw puzzle where half the pieces were buried under a parking lot.

They found the grammar. They found the syntax. They rebuilt the soul of a culture.

It wasn't easy. Some tribal members were skeptical. Why spend all this energy on "dead" words when there are modern problems like housing, healthcare, and land rights to worry about? But as the film We Still Live Here beautifully illustrates, the language is the land right. Without the language, the specific way the Wampanoag understand their relationship to the soil, the water, and each other is filtered through an English lens that doesn't quite fit.

Beyond the Movie: The Reality of Language Survival

If you watch the documentary today, you might wonder what happened after the cameras stopped rolling. Language reclamation isn't a "one and done" deal. It's a daily grind.

Today, the Mukayuhsak Weekuw (The Children’s House) serves as a Wôpanâak immersion school. It’s located in Mashpee. Little kids are learning to count, name colors, and describe their feelings in a language that their great-grandparents were told was useless. This is the "We Still Live Here" legacy in action.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

But there are hurdles. Funding is a constant nightmare. Government recognition of tribal lands is a legal see-saw. In 2020, the Mashpee Wampanoag faced a massive threat when the Department of the Interior tried to revoke their reservation status. While that was eventually overturned, it proved that the fight for existence is multi-front. The language provides a cultural backbone during these legal brawls. It’s hard to tell a people they don't exist when they are speaking a tongue that predates your government by millennia.

What People Get Wrong About Language Loss

People often use the term "extinct" when talking about Indigenous languages. The Wampanoag community hates that word. They prefer "sleeping."

Extinct implies it’s gone forever, like a dinosaur. Sleeping implies it can be woken up.

Another misconception is that this is just a hobby for "history buffs." It’s not. There is a deep psychological link between language and mental health. Studies across various Indigenous communities have shown that youth who are connected to their traditional language and culture have lower rates of suicide and substance abuse. It provides a sense of belonging that "standardized" education often fails to deliver.

The film We Still Live Here isn't just about the past; it's about the future of public health and community resilience.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Why the Story Persists in 2026

We live in a world that feels increasingly homogenized. We all use the same apps. We watch the same shows. The Wampanoag story is a middle finger to that trend. It says that local identity matters. It says that even if a culture is suppressed for centuries, it can breathe again.

It also changes how we view "The First Thanksgiving." We’ve all seen the construction-paper hats and the kitschy school plays. The Wampanoag are the people from that story. Seeing them not as "ghosts of the past" but as modern people—linguists, teachers, activists—reclaims the narrative. They aren't just characters in a 1621 dinner party. They are your neighbors in Cape Cod.

Key Milestones in the Reclamation

- 1993: Jessie Little Doe Baird begins her research.

- 2010: The documentary "We Still Live Here" premieres, bringing global attention.

- 2016: The opening of the immersion school, moving from adult classes to childhood education.

- 2020s: Continued expansion of the dictionary, which now contains over 10,000 words.

Actionable Steps for Supporting Indigenous Language

If the story of We Still Live Here moves you, don't just let it be a "nice thought." Language survival depends on active support and awareness.

- Educate yourself on the land you occupy. Use tools like Native-Land.ca to see whose ancestral territory you are living on. If you're in New England, there's a high chance you're on Wampanoag, Nipmuc, or Narragansett land.

- Support the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project directly. They are a non-profit. They need resources for curriculum development and teacher training. You can find them at wlrp.org.

- Change your vocabulary. Stop using words like "extinct" for living cultures. Use "dormant" or "reclaiming."

- Watch the film with a group. Hosting a screening of We Still Live Here in a library or school can spark conversations about local history that are usually ignored in textbooks.

- Demand better representation in local schools. Ask your school board if they include modern Indigenous history—not just "17th-century" history—in their curriculum.

The Wampanoag didn't ask for permission to bring their language back. They just did it. They proved that with enough documents, enough coffee, and enough sheer stubbornness, you can reverse the effects of centuries of erasure. The title says it all. They are still here. And now, they are finally being heard in their own words.