Paul McCartney was annoyed. It was late 1965, and he was sitting in his father’s house in Cheshire, trying to figure out why Jane Asher wouldn’t just listen to him. They were fighting. Again. Most couples argue about the dishes or being late, but when you're a Beatle in the middle of the most productive creative streak in human history, you turn that frustration into a number-one hit.

That’s how We Can Work It Out started. It wasn't some grand peace treaty. It was a warning.

People often mistake this track for a bubbly, optimistic anthem because of that driving acoustic guitar and the catchy "work it out" refrain. Honestly? It’s kind of a mean song. If you listen to the lyrics, Paul isn't really suggesting a compromise. He’s telling Jane that she’s wrong, he’s right, and she needs to hurry up and realize it before he loses interest. It’s the ultimate "my way or the highway" track disguised as a pop masterpiece.

The Day the Folk-Rock Sound Took Over

By the time the band got to EMI Studios (later Abbey Road) in October 1965, the pressure was immense. They needed a single for the Christmas market. They also had the Rubber Soul sessions looming. The Beatles weren't just a boy band anymore; they were becoming the vanguard of the counterculture, and the sound of We Can Work It Out reflected that shift toward a more mature, acoustic-driven "folk-rock" vibe.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney were still writing "eyeball to eyeball" during this period, but their differences were starting to bleed through the ink.

Paul had the "A" section. It was upbeat. It was in a major key. It was essentially him saying, "Life is short, so stop being difficult." But the song felt flat. It lacked the grit that made a Beatles record stand out from the dozens of imitators flooding the charts.

Then John stepped in.

Lennon’s Reality Check

Lennon took one look at Paul’s optimistic verses and decided the song needed a dose of cold, hard reality. He contributed the "B" section—the middle eight—where the tempo shifts and the mood turns sour.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

While Paul is singing about working it out, John is shouting, "Life is very short, and there's no time for fussing and fighting, my friend!" It’s a classic Lennon move. He took Paul’s personal relationship drama and turned it into a philosophical statement about the brevity of existence.

There’s a legendary bit of trivia here: John’s contribution was inspired by his growing interest in the concept of time and mortality, which would later peak with songs like "Across the Universe." He didn't care about Paul's girlfriend. He cared about the big picture.

The contrast is what makes the song work. You have the major key of the verse clashing against the minor key of the bridge. It’s musical tension at its finest. If the whole song had stayed in Paul's lane, it would have been a footnote. With John's intervention, it became a heavyweight contender.

That Weird Little Organ Sound

If you’ve ever listened to the track and wondered why it sounds like it’s being played at a dusty carnival, you’re hearing George Martin’s genius—and a harmonium.

During the recording on October 20, 1965, John Lennon decided to play a harmonium, which is basically a small reed organ that you pump with your feet. It gives the track a wheezing, droning quality. It’s strange. It shouldn't work in a pop song. But it provides this thick texture that fills the gaps between the acoustic guitars.

Actually, it took them two separate sessions to get it right. They spent nearly 11 hours on the first day just trying to nail the backing track. For a band that used to record entire albums in a single afternoon, 11 hours for one song was an eternity. It shows how much they cared about the tiny details by 1965. They weren't just "working it out"; they were reinventing how records were made.

The Waltz and the Shift

One of the coolest things about We Can Work It Out is the rhythm change during the bridge. George Harrison suggested it.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

He had been listening to more complex arrangements and suggested that the middle eight should shift into 3/4 time—a waltz. So, suddenly, the straight 4/4 pop beat disappears, and the song starts swaying like a drunken sailor. Then, just as quickly, it snaps back into the pop groove. This kind of rhythmic experimentation was unheard of on Top 40 radio at the time. It’s subtle, but it’s the reason the song feels so restless and urgent.

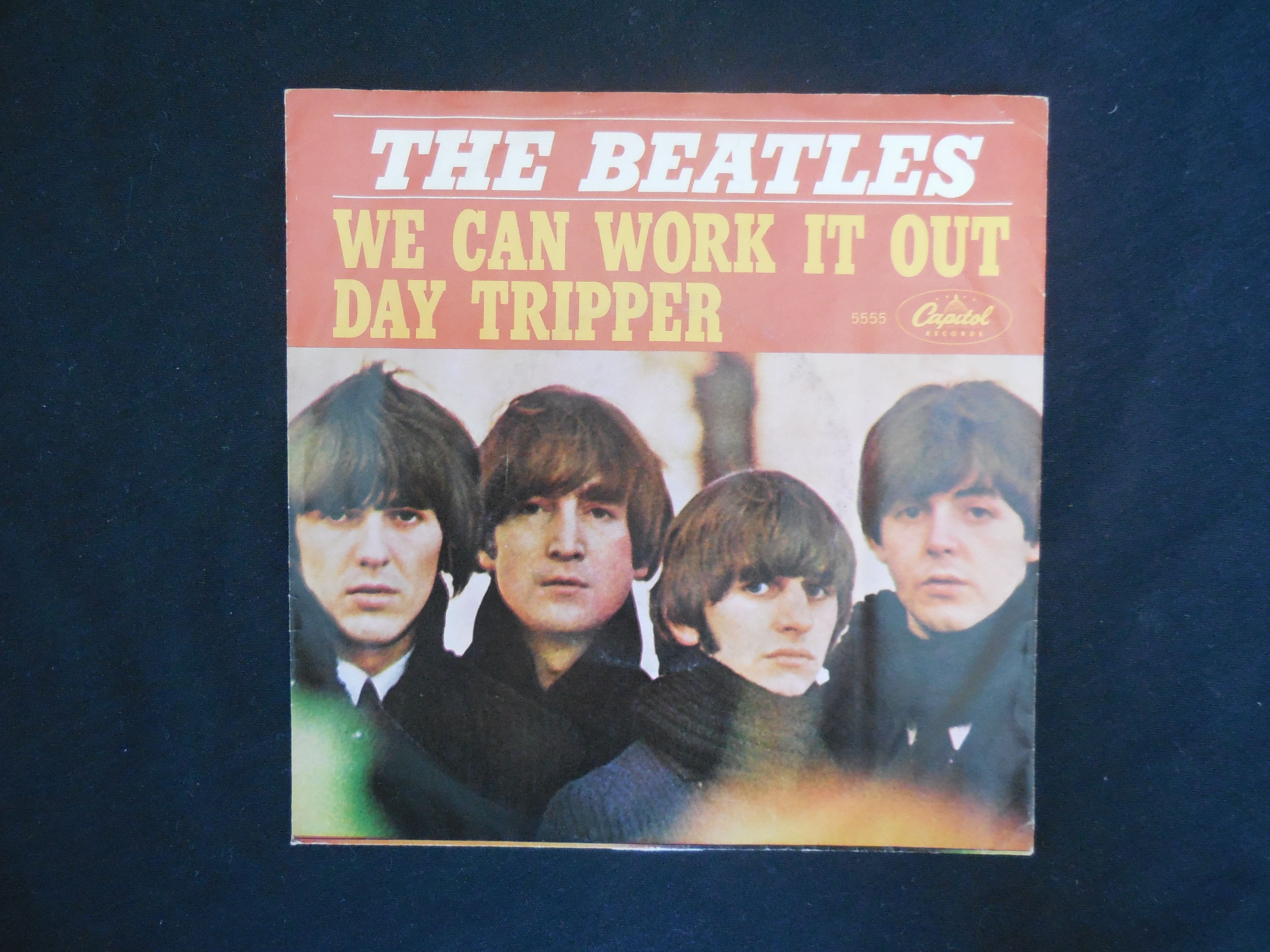

The Double A-Side Battle

When it came time to release the single, the band hit a snag. They had two incredible songs: We Can Work It Out and "Day Tripper."

John wanted "Day Tripper" to be the A-side because it had that killer guitar riff and a more "rock" edge. Paul, ever the PR-conscious diplomat, knew that We Can Work It Out was the bigger commercial hit. It was more "radio-friendly."

The compromise? The first-ever "Double A-side."

Instead of a "hit" on the front and a "filler" on the back, they marketed both songs as equals. It was a brilliant marketing move. It basically forced fans to buy the record because they were getting two masterpieces for the price of one. It hit number one in both the UK and the US, cementing 1965 as the year the Beatles truly owned the world.

Why We’re Still Talking About It in 2026

It’s easy to dismiss old pop songs as relics, but this one sticks. Why? Because the sentiment is universal, even if Paul was being a bit of a jerk to Jane Asher.

Everyone has had that argument. The one where you’re both saying the same thing but in completely different languages. Paul is saying "please," and John is saying "hurry up because we’re all going to die anyway." That tension is the human experience in a nutshell.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Also, the song represents the absolute peak of the Lennon-McCartney partnership. Soon after this, they started recording their parts separately. They started writing in their own houses. But on this track, you can hear them fighting for space. You can hear the two different personalities—the optimist and the cynic—trying to coexist in two minutes and fifteen seconds.

Essential Listening and Covers

If you want to really appreciate the architecture of the song, you have to hear Stevie Wonder’s 1970 cover. Honestly, some people argue it’s better than the original. Stevie turned the folk-rock drone into a funk powerhouse. He took the "work it out" line and made it sound like a celebration rather than a demand.

But even Stevie couldn't replicate that specific, biting vocal harmony between John and Paul on the original. That’s the secret sauce. When they hit that "my friend" line together, it’s chilling.

Putting the Song to Work for You

If you're a musician or a songwriter, there are a few tactical takeaways from We Can Work It Out that you can actually use:

- The Power of the Pivot: Don't be afraid to change time signatures. Moving from 4/4 to 3/4 in the bridge creates a "lift" that keeps the listener from getting bored.

- Contrast is King: If your verse is "sweet," make your bridge "sour." If the melody goes up, the lyrics should perhaps go down. The Beatles excelled at this emotional tug-of-war.

- Texture Over Volume: That harmonium isn't loud, but it's there. Sometimes a weird, quiet instrument adds more "heaviness" to a track than a wall of distorted guitars.

- Short and Sweet: The song is barely over two minutes. It doesn't overstay its welcome. It says what it needs to say and gets out. In an era of six-minute epics, there's a lot to be said for brevity.

Next time you’re in a disagreement with someone you care about, maybe don’t tell them "your way of thinking is the only way," like Paul did. But definitely put the record on. It might not solve the argument, but at least the soundtrack will be perfect.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Listen to the Mono Mix: Most streaming services default to the stereo mix where the vocals are panned hard right. Track down the mono version for a much more punchy, cohesive "wall of sound" experience.

- Analyze the Bridge: If you play guitar, practice the transition from the D chord in the verse to the B-minor/F-sharp sequence in the bridge. Notice how the mood shifts instantly.

- Explore the "Rubber Soul" Context: Listen to this song immediately followed by "In My Life" to see the full spectrum of Lennon and McCartney’s 1965 songwriting evolution.