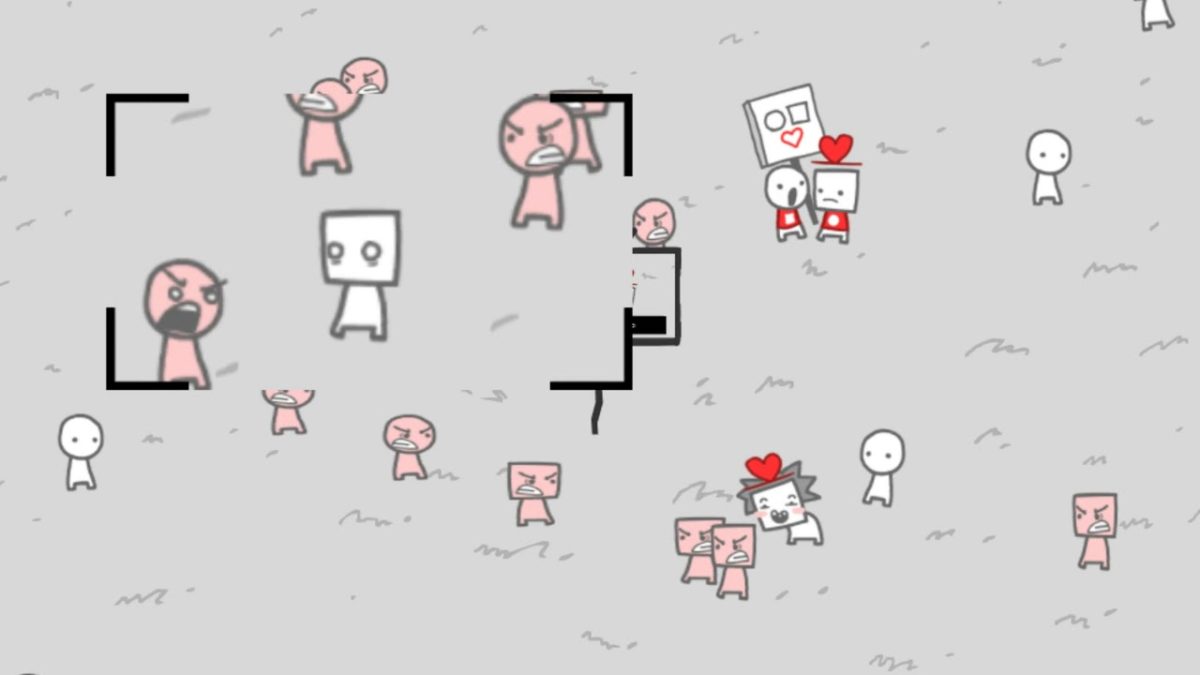

You ever feel like your brain is just a collection of the last ten things you saw on social media? It’s a gross feeling. Most people don't think about it, but Nicky Case thought about it back in 2016 and made a game that somehow feels more relevant in 2026 than it did when it first dropped. It’s called We Become What We Behold. It's barely a game. More like a playable panic attack. You spend five minutes taking photos of little "Peeps"—circle people and square people—and watching as a tiny camera lens turns a peaceful park into a literal bloodbath.

It’s weirdly simple. You’re the media. You have a viewfinder. You click.

Most games want you to be the hero, right? You save the world or build a city. Not here. In We Become What We Behold, you are the reason everything goes to hell. You ignore the couple sharing a moment or the guy wearing a silly hat because those don't get "likes" or "engagement" from the crowd watching the screen. Instead, you wait for a square to yell at a circle. Click. The screen flashes. The crowd gets angry. Then, the circles start getting angry back. It’s a feedback loop that feels uncomfortably like checking your phone at 2 AM.

The Brutal Logic of the Viewfinder

Nicky Case didn't just make a flash game; they made a mirror. The mechanics are intentionally shallow because the point isn't "skill." The point is how quickly you've been trained to seek out conflict.

Honestly, the first time I played it, I tried to be the good guy. I kept taking photos of the nice things. The game literally tells you "Crickets..." and nothing happens. The world doesn't move forward. To progress the story—to actually "play" the game—you have to be a bit of a jerk. You have to find the outlier, the one person acting weird or aggressive, and broadcast them to everyone else.

This is the core of We Become What We Behold. It’s based on a concept often attributed to Marshall McLuhan, the media theorist who famously said "we shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us." Case takes that academic idea and turns it into a cartoon where people start wearing pointy hats and carrying weapons because you showed them a picture of one person doing it. It’s "behavioral contagion" wrapped in a cute art style.

📖 Related: Is Half-Life 3 Confirmed? The Reality Behind the Memes and Leaks

Think about the "Screamers." In the game, a character starts shouting. If you photograph them, the caption says something like "CRAZY SQUARE ATTACKS." Suddenly, everyone is terrified of squares. The game doesn't need complex AI to show this. It just changes the sprites. The circles start looking nervous. The squares start looking defensive. It’s a rapid-fire descent into tribalism that happens in about three minutes of gameplay.

Why It’s Not Just "Media Criticism"

People love to say "the media is the problem," but that’s a lazy take. We Become What We Behold is sneakier than that. It’s about the interaction between the observer and the observed.

- The Peeps aren't inherently violent at the start.

- The photographer (you) isn't necessarily "evil," just looking for something interesting.

- The audience isn't "stupid," they're just reacting to what they see.

It’s a systemic failure. The game highlights how a system optimized for engagement—rather than truth or nuance—will always drift toward the most extreme version of reality. If you show a "normal" person, the meter doesn't move. If you show a "hateful" person, the meter goes off the charts. So, what do you do? You hunt for more hate.

The Viral Architecture of 2026

We’re living in the world this game warned us about. Look at how algorithms work today. Whether it’s a short-form video app or a news aggregator, the "viewfinder" is now automated. We’ve outsourced the role of the photographer to an AI that has one job: keep your eyes on the screen.

The game’s ending—which I won’t spoil if you’re one of the three people left who hasn't seen it—is hauntingly violent. But the violence isn't the point. The point is the silence that follows. After the explosion of anger and the final "news cycle," there’s nothing left. The park is empty. The cycle has consumed itself.

There’s a specific nuance here that Case nails. It’s the "Hat Peeps." At one point, you can photograph someone wearing a hat. It’s a fun, innocent trend. But even that gets twisted. The trend becomes a requirement. Then the trend becomes a target. It shows how even "good" or "neutral" viral moments are just fuel for the same machine that eventually creates the "bad" ones.

💡 You might also like: Skyward Sword Life Medal: The Weird Way to Reach 20 Hearts

Does it actually change how we think?

Psychologically, there’s a lot of weight to the idea that "beholding" changes the "becomer."

Researchers like George Gerbner talked about "Mean World Syndrome." It’s the idea that people who watch a lot of violent television believe the world is more dangerous than it actually is. We Become What We Behold is a literalized version of Mean World Syndrome. By forcing the player to capture the "mean" moments to progress, it forces the player to create a "mean world."

It’s kinda scary how fast it happens. You start the game feeling bad about ruining these people's lives. By the end, you're hovering your mouse, waiting for a circle to trip so you can mock them for the "story." You've been conditioned by the game's reward system—which is just the sound of a camera shutter and a little text box—to be a predator.

Taking the Viewfinder Back

So, what are we supposed to do? Delete our apps? Throw our phones into a lake?

Probably not. But We Become What We Behold suggests that awareness is the first step toward breaking the loop. When you realize the "camera" is biased toward conflict, you stop trusting every photo you see. You start wondering what was happening just outside the frame.

What the game doesn't show is the stuff that isn't photogenic. It doesn't show the long, boring process of building community or the quiet conversations that don't make for good "content." It only shows the snapshots.

Honestly, the most radical thing you can do after playing this is to go outside and look at something without trying to "capture" it. Don't frame it. Don't think about how you'd describe it to a group of strangers online. Just behold it without trying to make it "something."

Actionable Ways to Break the Cycle

If you've played the game and feel a bit gross about the state of the world, here’s how to actually apply those five minutes of gameplay to your real life:

- Audit your "viewfinder." Look at your social media feed. Is it mostly "Screamers"? If your feed is nothing but people being angry at other people, you are training your brain to see the world as a series of attacks. Unfollow the accounts that thrive on "CRAZY SQUARE ATTACKS" style content.

- Look for the Crickets. In the game, the peaceful moments are labeled as boring. In real life, lean into the boring. Support creators and journalists who focus on slow, nuanced stories rather than the "viral" pop of the day.

- Delay the Shutter. When you see something that makes you angry, wait. The game relies on your fast reaction. In reality, the "outrage" usually has a half-life of about six hours. If you don't photograph it (share it, comment on it, boost it) immediately, it often loses its power.

- Recognize the Frame. Every time you see a controversial clip, ask: "What is the photographer trying to make me behold?" Usually, there’s a "hat" or a "shouter" being used to make a point about an entire group of people.

Nicky Case made something that feels like a toy but acts like a vaccine. It gives you a small, controlled dose of media manipulation so that when you see it in the wild, you recognize it. It’s not about "fixing" the media—that's a big, messy job for another day. It’s about fixing your own relationship with the viewfinder.

The Peeps in the park didn't have a choice. They had to react to the screen. You’re not a Peep. You can choose to look away from the viewfinder whenever you want.