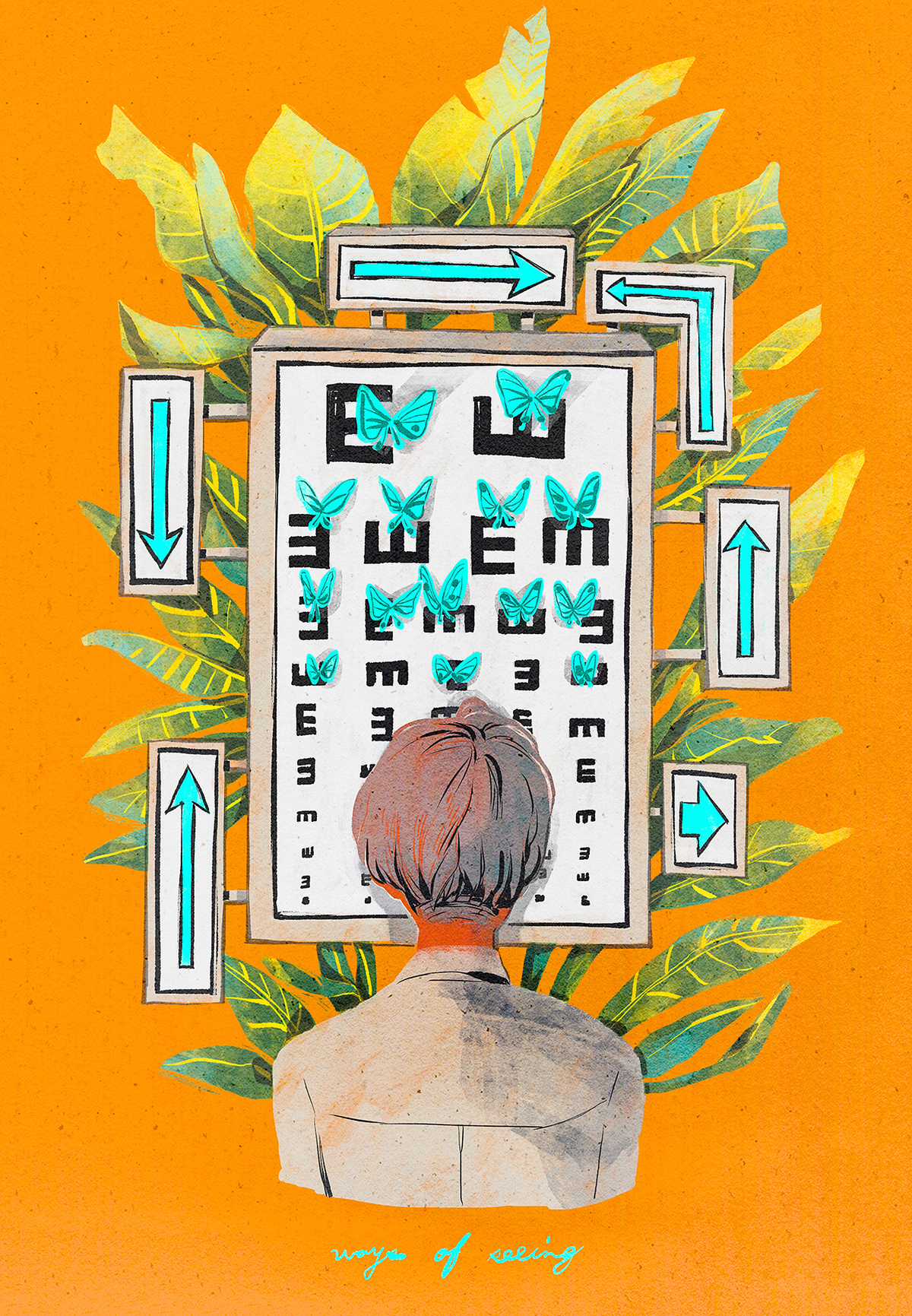

You think you're just looking. You walk into a gallery, or maybe you're just scrolling through Instagram, and you see an image. You assume your eyes are neutral tools, like a camera lens. But John Berger blew that idea apart back in 1972, and honestly, we still haven't quite recovered from it. When the BBC aired the first episode of Ways of Seeing Berger and his scruffy hair and patterned shirt appeared on screen, he wasn't just talking about oil paintings. He was talking about power.

Most people think art history is for folks in turtlenecks who enjoy quiet rooms. Berger didn't care about that. He wanted to show us that the way we see is an act of choice. It’s political. It’s social. And in a world where we are bombarded by more images in a single day than a person in the Middle Ages saw in a lifetime, his ideas are actually more relevant now than when the book first hit the shelves.

The Camera Changed Everything (And We Forgot)

Before the camera, a painting was part of a building. If you wanted to see the "Mona Lisa," you had to go to it. It was stationary. Unique. But Berger pointed out that the moment we could photograph art, the meaning of the image multiplied. It could be in a book, on a billboard, or in your bathroom.

This sounds obvious, right?

But here’s the kicker: when an image becomes "movable," its meaning changes based on what is around it. Berger used this famous example of a Van Gogh painting of crows over a wheatfield. If you look at it in silence, it’s one thing. If you put a caption under it saying "This is the last picture Van Gogh painted before he killed himself," the image changes instantly. The painting hasn't changed. You changed.

This is the core of Ways of Seeing Berger. He argued that the "authority" of art is often a facade used to keep people from trusting their own lived experience. We are told art is "mysterious" or "spiritual" to hide the fact that it often depicts very real, very ugly power dynamics.

The Male Gaze Before It Was a Buzzword

We talk about the "male gaze" all the time now. It’s all over TikTok and film theory essays. But Berger was one of the first to really dismantle how this works in European oil painting.

He noticed a weird pattern. In most classical nudes, the woman isn't just naked; she’s aware of being seen. She’s often looking at a mirror or directly at the viewer. Berger famously wrote that "men act and women appear." Women were taught to watch themselves being looked at. This created a split in the female psyche: the surveyor and the surveyed.

It’s a heavy concept.

📖 Related: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Think about how this translates to 2026. Look at front-facing camera culture. We are constantly curate-ing our own appearance because we have internalized the "surveyor." We aren't just living our lives; we are watching ourselves live them through an imaginary lens. Berger saw this coming. He saw that the "ideal" spectator was always assumed to be male, and the image was a commodity designed to flatter him.

Why the "Nude" Is Different from Being Naked

There is a distinction here that people often miss. Being naked is just being yourself, without clothes. It’s a state of being. But being "a nude" is an art form. It’s a costume of nakedness. In the European tradition, the nude was a way of turning the human body into an object for the owner of the painting.

Berger looked at paintings like Tintoretto's Susanna and the Elders and pointed out how the woman is basically performing her nakedness for the viewer, even though the story is supposed to be about her being harassed. It's a bit of a mind-bend. It forces you to ask: who is this image for? If you start asking that question about everything you see today—from Netflix posters to makeup ads—everything starts looking a lot different.

Oil Painting as a Status Symbol

We tend to romanticize the "Old Masters." We think of them as visionaries. While they were definitely talented, Berger reminds us that oil painting was the primary medium for showing off wealth.

Oil paint is unique because it can show texture, luster, and "thing-ness" better than almost anything else. If you bought an oil painting in the 17th century, you weren't just buying "art." You were buying a high-definition record of the things you owned. Your horses. Your land. Your gold-trimmed robes. Your wife.

It was the original "flex."

Berger argued that the medium of oil painting was inherently obsessed with possession. It said: "I can afford to have this rendered in three dimensions on my wall." This is why landscapes were so popular—not just because they were pretty, but because they depicted the borders of a landlord's property.

Publicity and the Dream of "The Future You"

The final part of Ways of Seeing Berger deals with what he calls "Publicity"—what we call advertising.

👉 See also: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

Advertising is basically the ghost of oil painting. It uses the same visual language. It uses the same lighting, the same compositions, and the same sense of texture. But there is a massive difference in how they function.

- Oil painting was about what the owner already had. It confirmed their status.

- Advertising is about what you don't have. It targets your anxieties.

Advertising tells you that your current life is inadequate. It proposes a "future you" who is more glamorous, more loved, and more successful because they bought a specific watch or a specific car. The irony? Publicity never celebrates the present. It’s always about a tomorrow that never arrives.

Berger's critique here is scathing. He suggests that advertising is a way of keeping people in a state of perpetual dissatisfaction so they keep working and consuming. It’s a cycle of envy. You see an image of someone who has been transformed by a product, and you envy that version of yourself.

Is Berger Still Right?

Look, some art historians hate John Berger. They think he’s too reductive. They argue that he ignores the purely aesthetic joy of a brushstroke or the genuine spiritual intent of certain artists. And they have a point. Not every painting is a tool of the patriarchy or a ledger for a landlord.

However, the "Berger Method" isn't about destroying art. It's about demystifying it.

The internet has actually proven him right in ways he probably couldn't have imagined. We live in the "age of the image" on steroids. When you see a "lifestyle influencer" posting a photo of their minimalist living room, they are using the exact same visual cues Berger identified in 18th-century Dutch interior paintings. They are showing you a curated reality designed to signify status and spark envy.

If we don't understand the Ways of Seeing Berger described, we are just passive recipients of these messages. We are being programmed without even knowing it.

How to Apply This Today

So, what do you actually do with this information? It's not just about winning an argument at a cocktail party. It’s about reclaiming your own eyes.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

First, stop trusting "neutrality." No image is neutral. Every photograph, every TikTok, every painting was made by someone with a perspective and a purpose. Ask yourself: "Who is the intended spectator for this?" If you’re looking at an ad for a luxury SUV, you might not be the intended spectator—you might just be the person meant to feel the envy that gives the owner their status.

Second, notice the "envy gap." When you feel that twinge of "I wish my life looked like that" while looking at a screen, recognize it as the "Publicity" machine Berger warned us about. That feeling isn't a reflection of your worth; it's a manufactured psychological state designed to make you spend money.

Third, look at the edges. Berger was great at looking at what was happening in the corners of paintings—the servants, the background, the subtle signs of ownership. Do the same with modern media. What is being cropped out? What is the frame hiding?

Practical Steps for a More Critical Eye

If you want to dive deeper, you don't need a PhD. You just need to change your habits.

- Read the book, obviously. It’s short. It’s mostly pictures. It’s one of the few "academic" books that actually feels like a conversation.

- Watch the original series. It’s on YouTube. Berger’s delivery is hypnotic, and the 70s aesthetics are actually pretty cool.

- The "Silence Test." Next time you see a powerful image with a caption, try to look at the image while ignoring the text. Does it feel different? Usually, the text is there to "anchor" a meaning that the image alone wouldn't have.

- Analyze your own photos. Look at your camera roll. How many of your photos are "for you" and how many are "for the surveyor"? It’s a humbling exercise.

Berger didn't want us to stop looking at art. He wanted us to look better. He wanted us to see through the "mystification" of history and realize that our sight is a form of power. Once you start seeing the world through this lens, you can't really go back to being a passive consumer. And honestly, that’s exactly the point.

The history of images is the history of how we've been told to see ourselves. By understanding the mechanics of that vision, we can start to define ourselves on our own terms, rather than through the lens of those who want to sell us a version of "the good life."

Take a look at the next billboard you pass. Don't just see the product. See the tradition it’s stealing from. See the gaze it's trying to capture. That's where the real power lies.