You're looking at a screen right now. Or maybe you're listening to a podcast while you drive. In both cases, you're swimming in a sea of invisible ripples. Whether it's the light hitting your retina or the Wi-Fi signal hitting your phone, everything comes down to one fundamental concept. To define wavelength of a wave, you basically have to look at the "stride" of energy.

Think about a person walking through sand. If they take giant, loping steps, the distance between their footprints is huge. If they’re power-walking like a frantic commuter, those footprints are jammed together. Wavelength is just that—the physical distance between one peak of a wave and the very next one.

It sounds simple. It isn't.

What Does it Actually Mean to Define Wavelength of a Wave?

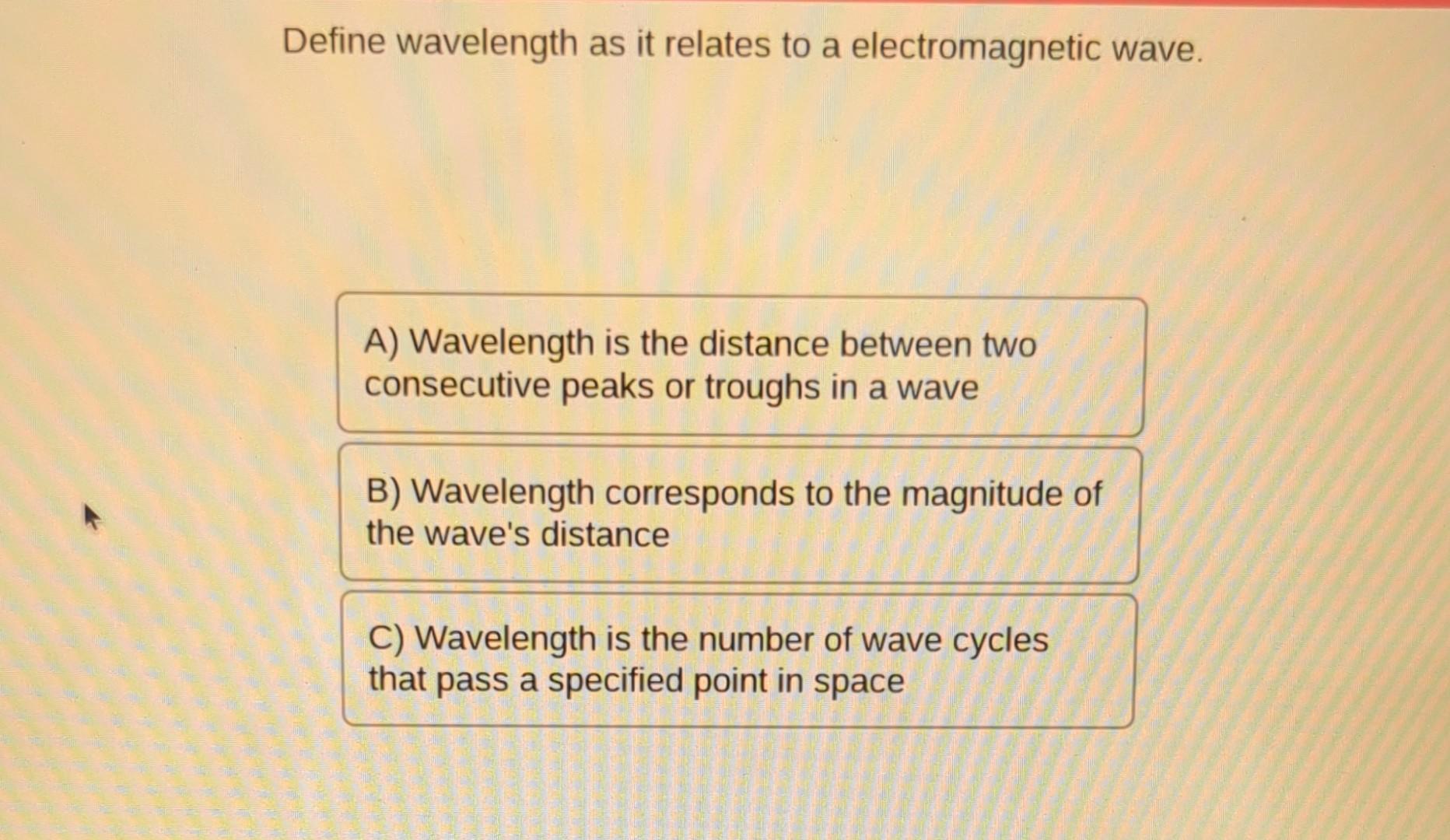

If we're being precise, the wavelength of a wave is the spatial period of the wave. It’s the distance over which the wave's shape repeats. You’ve probably seen the classic "S" curve in a physics textbook. You pick a point—let's say the very top, the crest—and you measure the distance to the next identical top.

That’s your wavelength.

We usually use the Greek letter lambda, which looks like an upside-down "y": $\lambda$.

But waves aren't just squiggles on a page. In the real world, they are three-dimensional pulses of pressure or electromagnetic fields. When you talk about sound, you’re talking about longitudinal waves. Here, the "peaks" are actually areas where air molecules are smashed together (compressions), and the "troughs" are where they’re stretched apart (rarefactions). To define wavelength of a wave in a sound context, you measure the distance between those high-pressure zones.

🔗 Read more: Why a 9 digit zip lookup actually saves you money (and headaches)

The Math You Actually Need

Physics isn't just about drawing lines; it's about how those lines behave when things get fast. There is a rigid, unbreakable relationship between wavelength, frequency, and speed.

The formula is $v = f\lambda$.

Basically, the velocity ($v$) of a wave is its frequency ($f$) times its wavelength ($\lambda$). This creates an inverse relationship that defines how our technology works. If the frequency goes up (the wave vibrates faster), the wavelength must get shorter. It’s a trade-off.

Imagine you’re shaking a rope. Shake it slowly, and you get long, lazy undulations. Shake your hand like you’ve just been stung by a bee, and those waves get tight and short. This isn't just a classroom experiment. It’s why your 5GHz Wi-Fi is faster but has a shorter range than 2.4GHz. The shorter waves carry more data but they can't punch through a brick wall as easily as the long, "lazy" waves of a lower frequency.

Why Color is Just a Ruler

Ever wonder why a strawberry is red? It’s not because the strawberry "is" red in some cosmic sense. It’s because the molecular structure of the fruit's skin reflects light with a wavelength of roughly 700 nanometers.

Our eyes are essentially biological rulers. We have specialized cells called cones that are tuned to specific "strides" of light.

💡 You might also like: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

- Violet light is the frantic sprinter of the visible spectrum, with a wavelength around 380-450 nanometers.

- Red light is the marathon runner, stretching out to about 625-750 nanometers.

Anything longer than red? That’s infrared. You can’t see it, but you feel it as heat. Anything shorter than violet? That’s ultraviolet. It’s too "fast" for your eyes to register, but it’s plenty energetic enough to give you a sunburn.

The Weird World of Radio and Beyond

When we define wavelength of a wave in the context of radio, things get massive. We aren't talking about nanometers anymore. We’re talking about kilometers.

Back in the early days of maritime radio—think the era of the Titanic—operators dealt with "longwave" signals. Some of these waves were over 2,000 meters long. Imagine a single wave crest passing you, and the next one not arriving until two kilometers later. These waves are incredible at hugging the Earth's curvature, which is why they were used for long-distance communication across oceans.

On the flip side, look at X-rays. Their wavelengths are so incredibly tiny—about the size of an atom—that they don't bounce off your skin. They slide right through the gaps between your cells, only getting stopped by the denser "forest" of atoms in your bones.

Common Misconceptions: It’s Not Just About "Up and Down"

People often confuse wavelength with amplitude.

Amplitude is how "high" the wave is. It's the volume of a sound or the brightness of a light.

Wavelength is the horizontal distance.

You can have a very quiet sound (low amplitude) that has a very deep pitch (long wavelength). Or a blindingly bright blue light (high amplitude, short wavelength). They are independent variables.

📖 Related: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

Also, the medium matters. A wave's frequency stays the same when it moves from air into water, but its speed changes. Because the speed changes, the wavelength must change too. Light actually slows down and its wavelength "scrunches up" when it hits glass or water. This is why a straw looks broken in a glass of water—the wavelengths are physically changing their stride as they enter the denser material, causing the light to bend (refraction).

Practical Applications for Your Life

Understanding how to define wavelength of a wave isn't just for people in lab coats. It affects your daily tech more than you think.

- Noise Canceling Headphones: These work by "reading" the wavelength of incoming noise and generating an "anti-wave" that is exactly out of phase. It aligns a trough with every peak, effectively flattening the wave to zero.

- Microwave Ovens: Your microwave is specifically designed to create "standing waves" with a wavelength of about 12 centimeters. This specific size is perfect for vibrating water molecules. This is also why your microwave has "hot spots" and "cold spots"—the peaks of the waves are where the cooking happens.

- Astronomy: We know the universe is expanding because of "redshift." When a galaxy moves away from us, the light it emits gets stretched out. The wavelength becomes longer (redder). It’s like the Doppler effect you hear when a siren passes you and the pitch drops.

Real-World Limits

We have to acknowledge that at a certain point, the classical definition of a wave starts to get... fuzzy. In quantum mechanics, particles like electrons also behave like waves (the de Broglie wavelength). At that scale, trying to "measure" the distance between peaks becomes a matter of probability rather than a simple ruler measurement.

Actionable Insights for Using Wavelength Knowledge

If you’re trying to optimize your home or work environment, keep these wavelength "rules of thumb" in mind:

- Check your Router Placement: If you're using a 5GHz band, remember those wavelengths are only about 6 centimeters long. They are easily blocked by furniture and walls. Keep the router high and in the open.

- Blue Light Management: If you’re struggling to sleep, it’s because the short, high-energy wavelengths of blue light (around 450nm) suppress melatonin. Use a "warm" filter on your phone to shift the output to longer, redder wavelengths.

- Sound Treatment: To stop deep bass (long wavelengths) from vibrating through your apartment walls, you need much thicker material than you do for high-pitched sounds. Thin foam kills echoes, but only mass stops the long "thump" of a sub-woofer.

To truly define wavelength of a wave, you have to stop seeing objects as solid things and start seeing them as filters. Everything around you is either absorbing, reflecting, or stretching these invisible distances. Once you see the world through the lens of $\lambda$, the way your phone, your eyes, and your microwave work suddenly makes a lot more sense.