Tucked away on the banks of the Tennessee River, the Watts Bar Nuclear Power Plant doesn't look like a record-breaker. It looks like a massive industrial fortress, which, to be fair, it is. But if you’re into energy or just wondering where your lights come from in the Southeast, this place is legendary for reasons that have nothing to do with aesthetics. It’s the last site in the United States to bring a "new" reactor online in the 21st century before the Vogtle expansion in Georgia finally caught up.

Watts Bar is weird. It’s a survivor of an era when the U.S. almost gave up on nuclear power entirely.

Construction started way back in 1973. Think about that for a second. Nixon was in the White House. People were still wearing bell-bottoms. Yet, Unit 2 didn't actually start commercially operating until 2016. That is a forty-year gap. You’ve got a facility that is simultaneously a relic of the Cold War era and one of the most technologically updated bastions of the modern power grid. It’s a strange, hybrid beast managed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

The Longest Construction Project in History?

Honestly, the timeline of the Watts Bar Nuclear Power Plant is enough to make any project manager wake up in a cold sweat. By 1985, the TVA hit the brakes. Hard. They suspended construction on both units because of a mix of safety concerns, shifting regulations, and a projected drop in energy demand.

Unit 1 eventually got its act together and started humming in 1996. But Unit 2? It sat there. It was basically a giant, expensive time capsule. For decades, it was roughly 80% finished, just waiting for someone to decide if it was worth the multi-billion dollar price tag to cross the finish line.

In 2007, the TVA decided to go for it. They looked at the carbon emissions from coal and the rising need for "baseload" power—the stuff that keeps the grid stable when the sun isn't shining—and realized they needed Watts Bar Unit 2. It wasn't cheap. We are talking about $4.7 billion just for the completion phase.

💡 You might also like: Memphis Doppler Weather Radar: Why Your App is Lying to You During Severe Storms

What makes it different from other plants?

Most nuclear plants are just there to make electricity. Watts Bar has a side hustle. It is the only nuclear plant in the country that helps maintain the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

They use something called Tritium-Producing Burnable Absorber Rods (TPBARs). Basically, instead of just using standard boron rods to control the reactor's "burn," they use these specialized rods that capture neutrons to create tritium. Tritium is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen that’s essential for modern nuclear warheads. Because of international treaties, the U.S. can't use "civilian" reactors for this if they use foreign-enriched uranium. Since the TVA is a corporate agency of the federal government, Watts Bar fits the legal loophole perfectly.

Safety Post-Fukushima: The Reality Check

You can't talk about Watts Bar without talking about safety. Because Unit 2 was being finished right as the Fukushima Daiichi disaster happened in 2011, the NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) went into overdrive.

They didn't just build it; they overbuilt it.

The plant sits in a flood-prone area, so the "FLEX" equipment—portable generators and pumps—is stored in hardened buildings designed to survive the kind of "once in a thousand years" event that most people don't even like to think about. There are seismic reinforcements that weren't even in the original blueprints.

📖 Related: LG UltraGear OLED 27GX700A: The 480Hz Speed King That Actually Makes Sense

Is it perfectly safe? Nothing is. But the level of scrutiny on Watts Bar is arguably higher than almost any other site in the country because it was the first "post-Fukushima" reactor to be licensed.

The Carbon Argument

People get heated about nuclear. It’s expensive. The waste is a headache. But look at the numbers for a second.

Watts Bar generates about 2,300 megawatts of electricity. That is enough to power roughly 1.3 million homes. If you tried to replace that with coal or gas, the CO2 output would be astronomical. The TVA likes to brag that their nuclear fleet, led by Watts Bar, is the reason they can even talk about hitting "net-zero" goals. Without these two domes in Rhea County, the Tennessee Valley's carbon footprint would look a lot different.

Myths People Still Believe About Watts Bar

One big misconception is that the plant is "old."

Sure, the concrete was poured in the 70s. But inside? The control rooms for Unit 2 look like something out of a modern tech firm, not a 1970s submarine. They replaced thousands of miles of wiring and upgraded the analog dials to digital interfaces.

👉 See also: How to Remove Yourself From Group Text Messages Without Looking Like a Jerk

Another myth: "It’s going to explode like Chernobyl."

Nope. Physics says no. Watts Bar uses a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) design. Unlike the Soviet RBMK reactors, PWRs have a "negative temperature coefficient." Basically, if the water gets too hot and turns to steam, the nuclear reaction naturally slows down because it loses the "moderator" it needs to keep the fission going. It's built to fail-safe, not fail-explosive.

Understanding the Economic Impact

The plant isn't just a giant battery; it’s an economic engine. It employs over 1,000 permanent workers. During "outages"—the periods every 18 to 24 months when they shut down to refuel—they bring in another 1,000+ contractors. Small towns like Spring City basically live and breathe based on the plant's schedule.

But there is a flip side. The cost overruns on Unit 2 were massive. Critics often point to Watts Bar as the prime example of why we shouldn't build nuclear. They argue that $5 billion could have bought a lot of wind turbines and solar panels.

The counter-argument? You can't run a massive aluminum smelter or a data center on a cloudy day with just solar. You need that heavy, constant "baseload" that only nuclear or fossil fuels can provide right now.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you’re trying to wrap your head around whether nuclear is the future or a dead end, Watts Bar is the case study you need to look at. Here is how you can actually engage with this topic or use this info:

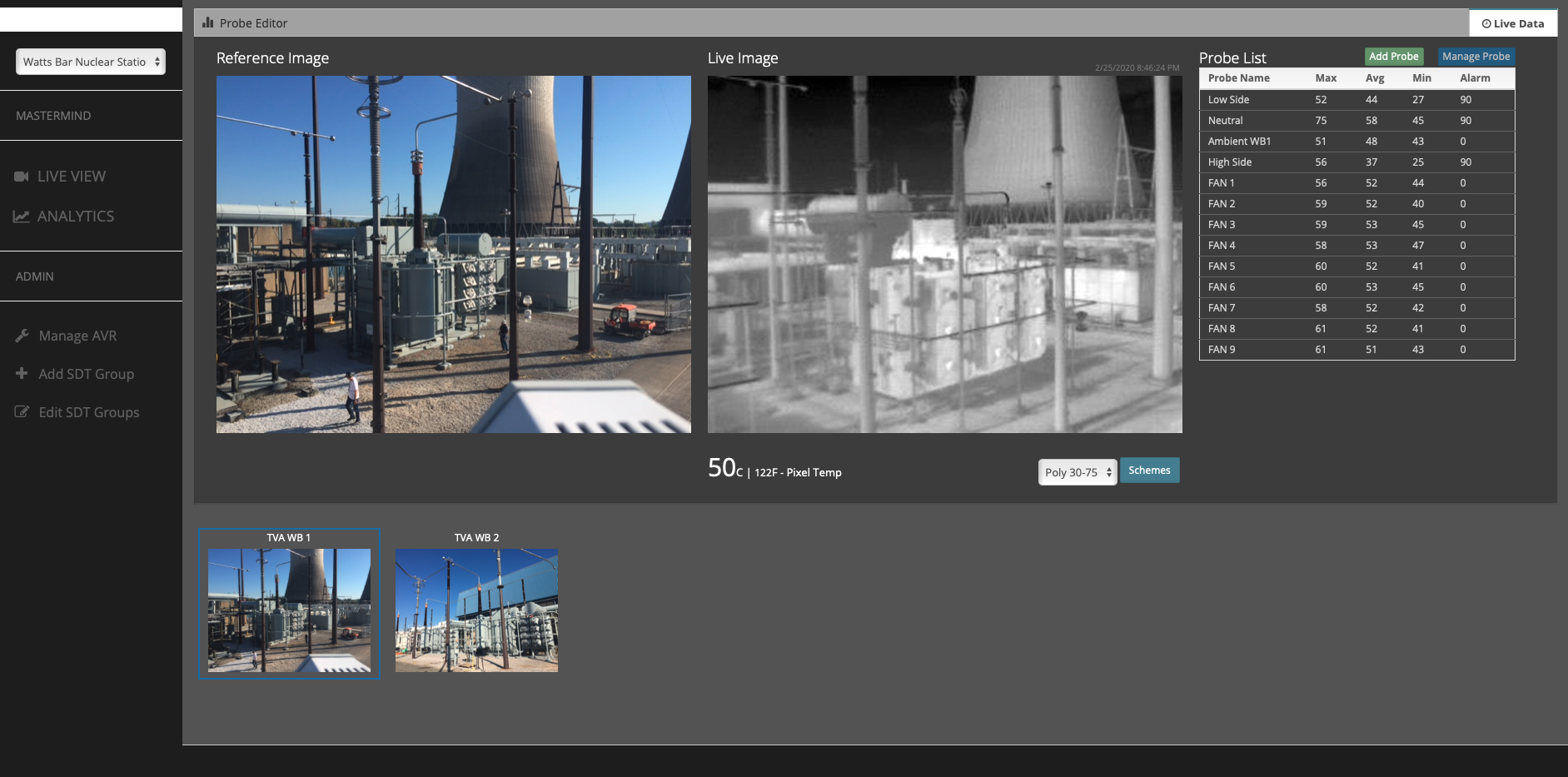

- Track the Grid: Check out the TVA's real-time energy map. You can see exactly how much of the Valley's power is coming from nuclear at any given moment. It’s usually a massive chunk—often over 40%.

- Property Values and Safety: If you’re looking at real estate in East Tennessee, don’t let the "Nuclear" label scare you off. Studies on property values near plants like Watts Bar generally show they are stable because of the high-paying jobs the plant provides. Plus, the NRC emergency planning zones (EPZs) are extremely well-documented; you can find the 10-mile and 50-mile radius maps online to understand exactly where you sit.

- Tour the Area: While you can’t just wander into the reactor building (for obvious reasons), the TVA has a public overlook near the dam. It’s one of the few places in the country where you can see the scale of a twin-unit nuclear site against the backdrop of a massive hydroelectric project.

- The Waste Question: Be aware that "spent fuel" is currently stored on-site in dry casks. This is a temporary solution that has become permanent because the U.S. doesn't have a central repository (like Yucca Mountain). If you're advocating for or against nuclear, this is the specific technical hurdle you should focus on.

Watts Bar is a weird, clunky, expensive, and absolutely vital piece of infrastructure. It’s a bridge between the 20th-century dream of "power too cheap to meter" and the 21st-century reality of a carbon-constrained world. Whether it’s a success or a cautionary tale depends entirely on which column of the ledger you're looking at.