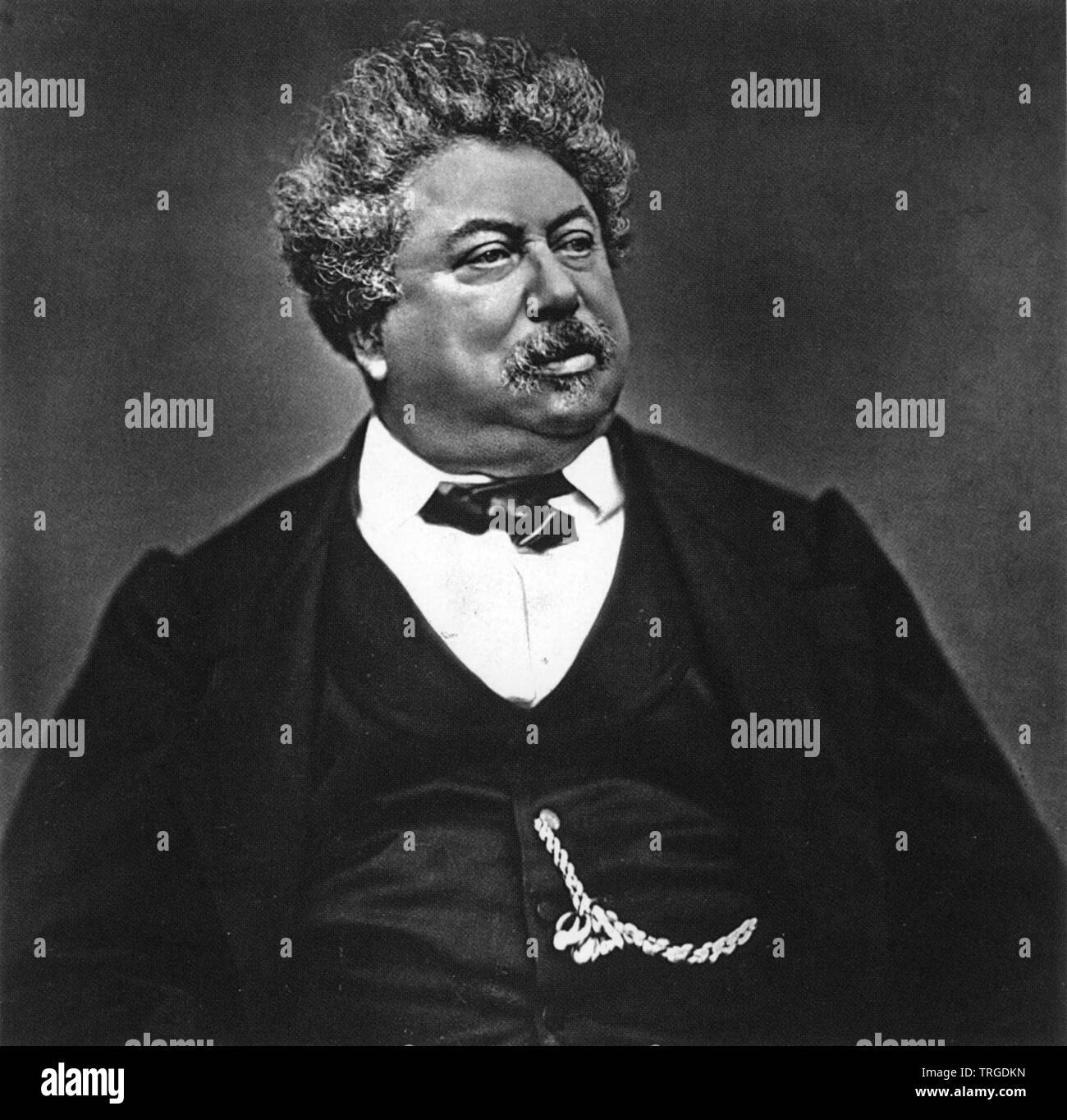

If you’ve ever sat through a marathon of The Three Musketeers or stayed up way too late turning pages of The Count of Monte Cristo, you’ve met the mind of Alexandre Dumas. But here’s the thing that surprises a lot of people: the man behind those French classics wasn't just some powdered-wig aristocrat with a quill. He was a person of color.

So, was Alexandre Dumas Black? Honestly, the answer is a resounding yes, though with the nuance of 19th-century history. Dumas was a "quadroon," a term used back then to describe someone who was one-quarter Black. He was the grandson of an enslaved woman and a French nobleman, and that heritage didn't just sit in the background of his life—it defined his struggles, his triumphs, and the very stories he wrote.

The Epic Roots: Marie-Cessette and the Marquis

To understand Dumas, you have to look at his father, Thomas-Alexandre. He was basically a real-life superhero. Thomas-Alexandre was born in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) to the Marquis Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie and an enslaved Black woman named Marie-Cessette Dumas.

Life was messy. The Marquis actually sold Thomas-Alexandre into slavery for a bit just to raise travel money to go back to France, only to "buy" him back once he’d secured his inheritance. Talk about a toxic family dynamic. Once in France, Thomas-Alexandre became a legendary general in Napoleon’s army. He was a giant of a man, famously nicknamed the "Black Devil" by his enemies because he was so terrifyingly good at combat.

- Marie-Cessette Dumas: An enslaved woman of African descent.

- Thomas-Alexandre Dumas: The first person of color to become a general-in-chief in the French army.

- Alexandre Dumas (the author): Born in 1802, the son of the general.

Dumas took his last name from his grandmother, Marie-Cessette, rather than his grandfather's noble title. It was a statement. He was leaning into his identity long before it was "cool" or safe to do so.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Facing the Critics and the Caricatures

Dumas was a massive celebrity in Paris. Think of him like a modern showrunner—he was churning out plays and novels at a rate that made people suspicious. Because he was so successful and so visibly of mixed race, his enemies came for him with everything they had.

They drew racist caricatures of him with exaggerated features. They mocked his hair. They claimed he used "ghostwriters" (whom they called his "niggers") because they couldn't wrap their heads around a man of African descent being the most prolific writer in France.

He didn't take it lying down.

There’s this famous story—it might be slightly embellished, but it’s pure Dumas—where a man insulted his lineage. Dumas reportedly shot back: "My father was a mulatto, my grandfather was a Negro, and my great-grandfather a monkey. You see, Sir, my family starts where yours ends."

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s a brutal, witty mic-drop. He knew exactly who he was.

How His Heritage Bleed Into the Books

While The Three Musketeers feels like a classic French romp, many scholars, including Tom Reiss, author of the Pulitzer-winning biography The Black Count, argue that Dumas’s work is deeply autobiographical.

Take The Count of Monte Cristo. It’s a story about a man who is unjustly imprisoned, forgotten by the world, and returns to seek justice. This mirrors the tragic end of his father’s life. General Dumas was captured and thrown into a dungeon by the Kingdom of Naples while Napoleon basically ignored him. He came home a broken man and died when Alexandre was just four.

The themes of:

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

- Wrongful imprisonment

- The struggle for identity

- Outsiders fighting for a place in society

These weren't just plot points. They were the lived experience of the Dumas family. He even wrote a novel called Georges that deals directly with race and colonialism in Mauritius, which is probably his most overt exploration of his own background.

The Erasure of the "Black Count"

For a long time, history tried to "whiten" Dumas. When you look at old portraits or early film adaptations, his African features were often softened or ignored. It wasn't until 2002—two centuries after his birth—that France finally moved his remains to the Panthéon, the highest honor a French citizen can receive.

President Jacques Chirac admitted during the ceremony that "the wrong" had finally been righted. He acknowledged that Dumas had faced a lifetime of racism that the French literary establishment had tried to bury.

Basically, Dumas was too big to be ignored, but too Black to be fully embraced by the elites of his time.

What You Can Do Now

If you want to see the "real" Dumas, don't just stick to the movies.

- Read "The Black Count" by Tom Reiss. It’s a gripping biography of the General that reads like an action novel.

- Check out "Georges." It's a shorter read than his big doorstops and gives you a direct look at how he viewed race.

- Visit the Musée Alexandre Dumas in Villers-Cotterêts if you're ever in France; it houses amazing artifacts from all three generations of the Dumas men.

Alexandre Dumas wasn't just a Black writer; he was a powerhouse who forced the world to acknowledge his genius while they were busy staring at his skin. Knowing his history doesn't just change how you see the man—it changes how you read every single "All for one, and one for all."