Warner Bros. hated it. Jack Warner, the legendary studio head, famously thought it was a "three-car-garage" kind of picture—small, messy, and a bit of a throwback to the gangster flicks of the 1930s. He was so convinced the film would flop that he offered its star and producer, Warren Beatty, a deal that sounded like a brush-off: forty percent of the gross receipts.

Mistake. Huge.

The film ended up making over $70 million, turning a first-time producer into one of the wealthiest men in Hollywood. But the money was just the side effect. When we talk about Warren Beatty Bonnie and Clyde, we aren’t just talking about a movie. We’re talking about the moment the old studio system died and the "New Hollywood" was born.

The Producer Who Wouldn't Take No for an Answer

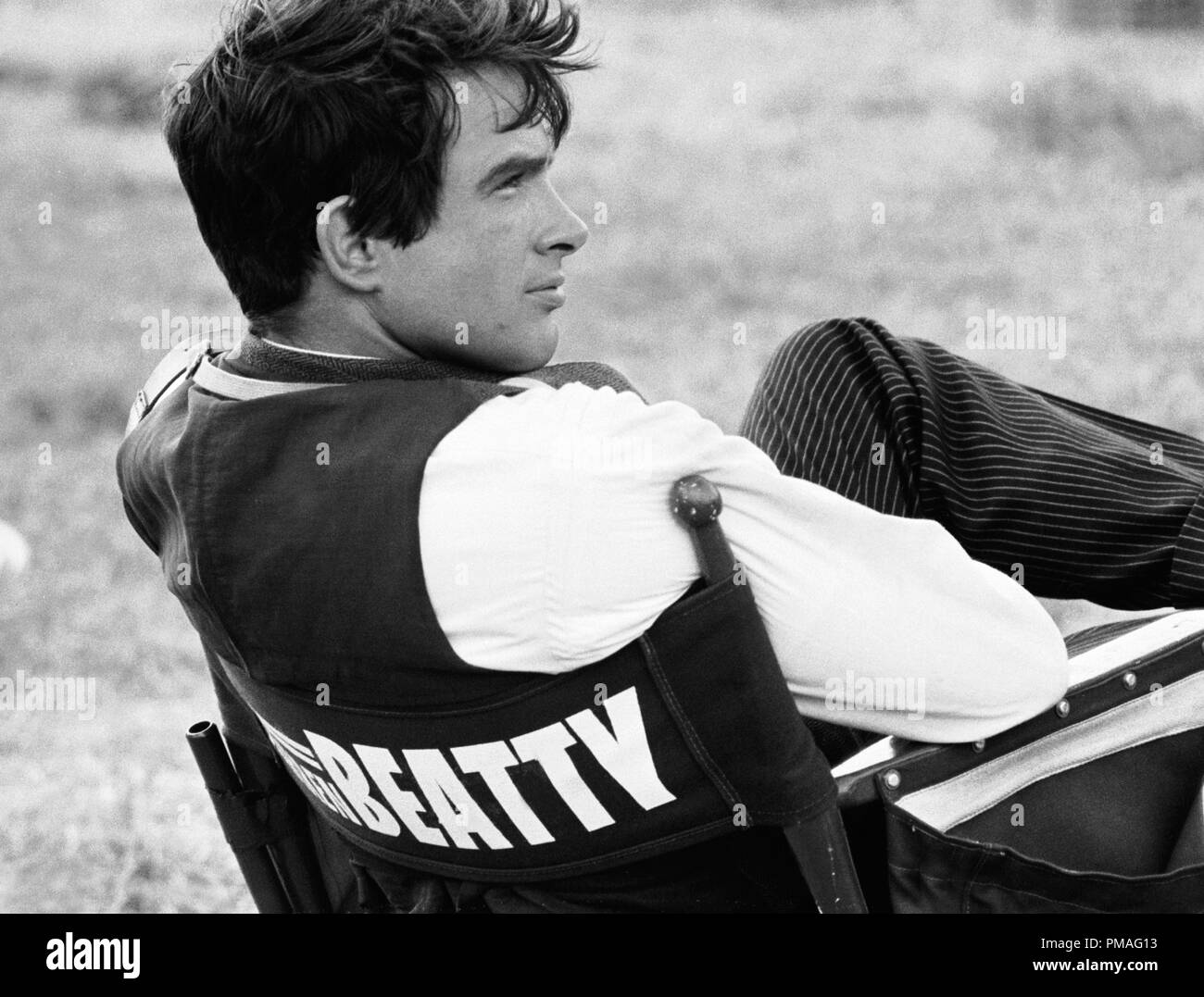

Warren Beatty wasn't exactly the most experienced guy behind the camera in 1966. He was a heartthrob. He had the looks, the charm, and a few solid acting credits, but he wanted control. He found the script by David Newman and Robert Benton after it had been rejected by almost everyone, including French New Wave icons François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard.

Honestly, it’s a miracle it ever got made.

Beatty spent months chasing directors. He went through a dozen names—George Stevens, William Wyler, Sydney Pollack. They all said no. Eventually, he circled back to Arthur Penn. Penn had worked with Beatty before on Mickey One, a weird, experimental film that didn't exactly set the world on fire. Penn initially turned him down, too. Beatty, in a move that basically defined his legendary persistence, supposedly begged on his knees to get Penn to sign on.

It worked.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

The collaboration was friction-heavy. Beatty was the producer who wanted to be involved in everything; Penn was the director who wanted to push the aesthetic boundaries of violence and sex. They fought over the script. They fought over the casting. For a while, Beatty’s sister, Shirley MacLaine, was considered for the role of Bonnie. But once Beatty decided he had to play Clyde, that idea (rightfully) went out the window.

Why the Violence Was Different

If you watch it now in 2026, the violence might seem "normal." You’ve seen John Wick. You’ve seen Tarantino. But in 1967, people were used to the "Production Code." If a guy got shot, he clutched his chest, there was a tiny smudge of red, and he fell over.

Bonnie and Clyde changed the physics of cinema.

Penn used squibs—tiny explosives with bags of fake blood—to show the impact of bullets. He used slow motion during the final ambush to make the death of the outlaws feel like a "ballet of blood." It wasn't just gore for the sake of it. It was a reflection of the Vietnam War footage that was starting to bleed into American living rooms every night. The audience was ready for something real. The critics? Not so much.

The Critical Backlash (And the Turnaround)

When the film first premiered, the "Old Guard" of critics absolutely trashed it. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times hated it so much he wrote three separate negative reviews. He called it a "cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick." He thought it was irresponsible to make murderers look like glamorous fashion icons.

He was wrong. And the kids knew he was wrong.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

Younger audiences flocked to the theaters. They saw themselves in Bonnie and Clyde—two beautiful, bored people railing against a system (the banks) that they didn't understand and didn't like. This wasn't a movie for the people who grew up on The Sound of Music. This was for the generation that was about to experience Woodstock.

The turning point came when Pauline Kael wrote a 9,000-word defense of the film in The New Yorker. She recognized that the movie was doing something new: it was mixing comedy with tragedy in a way that felt like life. One minute you're laughing at the "C.W. Moss" antics, and the next, a face is being blown off through a car window. That tonal whiplash was the future of movies.

Warren Beatty's Vision for Clyde

There’s a detail most people forget: Beatty wanted Clyde to be impotent.

In the real history of the Barrow Gang, there were rumors about Clyde's sexuality. Some early script drafts even hinted at a bisexual ménage à trois. Beatty and Penn eventually settled on impotence because it added a layer of tragedy to the character. Clyde could rob banks, he could kill, he could lead a gang, but he couldn't perform the one thing Bonnie actually wanted. It made them "sad lovers" instead of just "criminals."

This choice made the film more vulnerable. It wasn't just a tough-guy act. Beatty played Clyde with a sort of fidgety, nervous energy that felt human. He wasn't a superhero. He was a guy who was good with a gun because he didn't know how to be good at anything else.

The Business of Being Warren Beatty

You've gotta respect the hustle. Because Warner Bros. had so little faith, they didn't even want to release it properly. They buried it in second-run theaters and drive-ins.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

Beatty fought them.

He used his producer power to demand a re-release and a proper marketing campaign. He understood that the fashion—the berets, the long skirts, the tailored suits—was going to be a massive trend. He was right. Bonnie Parker’s look became the "it" style of 1968. By the time the Academy Awards rolled around, the film had ten nominations.

It only won two (Best Supporting Actress for Estelle Parsons and Best Cinematography), but it didn't matter. The message was sent: the era of the big-budget, safe studio musical was over. The era of the auteur, the producer-star, and the gritty antihero was here.

How to Watch It Today

If you're going to dive into this piece of history, don't look for a documentary. Look for the 1967 film.

- Watch the ending first (if you must): It’s the most famous scene in movie history for a reason. Note the editing. Dede Allen, the editor, used "jump cuts" and varying speeds to make it feel chaotic. It was revolutionary.

- Look at the lighting: Burnett Guffey won an Oscar for the cinematography. He hated the way Penn wanted to shoot—it was too "messy" for an old-school guy—but the result is a dusty, sun-drenched Texas that feels like a dream and a nightmare at the same time.

- Focus on Gene Hackman: Before he was Lex Luthor or Popeye Doyle, he was Buck Barrow. It’s one of the best supporting performances of the 60s.

The legacy of Warren Beatty Bonnie and Clyde is everywhere. You see it in The Godfather, in The French Connection, and every time a modern director decides to make a movie about "cool" criminals. It proved that you could be violent, you could be controversial, and you could still be a star.

Next Steps for Film Buffs

To truly understand the impact of this film, your next move should be to compare it to the 1930s gangster films like Public Enemy. Notice how different the moral compass feels. If you want to see where Warren Beatty went next with this power, track down a copy of Shampoo (1975). It shows his evolution from the "outlaw" to the "insider" of a crumbling Hollywood.