You’ve probably seen the painting. Or at least, you’ve seen the mood. A hunched figure, limbs all angles and sorrow, clutching a guitar that isn't actually blue in the original oil on canvas, but feels blue in every sense of the word. That’s Picasso’s The Old Guitarist from his Blue Period. But in 1937, a suit-and-tie insurance executive named Wallace Stevens took that image and turned it into a poem that basically broke the brain of modern literature.

The Man with the Blue Guitar isn't just a poem about music. It’s a 33-section existential crisis set to a rhythm that mimics the strumming of a cheap instrument.

Stevens was a weird guy. By day, he was the Vice President of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company. He never learned to drive. He composed his poems on scraps of paper while walking to work. People think of poets as starving artists in garrets, but Stevens was a corporate powerhouse who happened to be obsessed with how we perceive reality. When he wrote about the blue guitar, he was asking a question that we are still screaming into the void today: Can art ever actually tell the truth?

The Great Disconnect

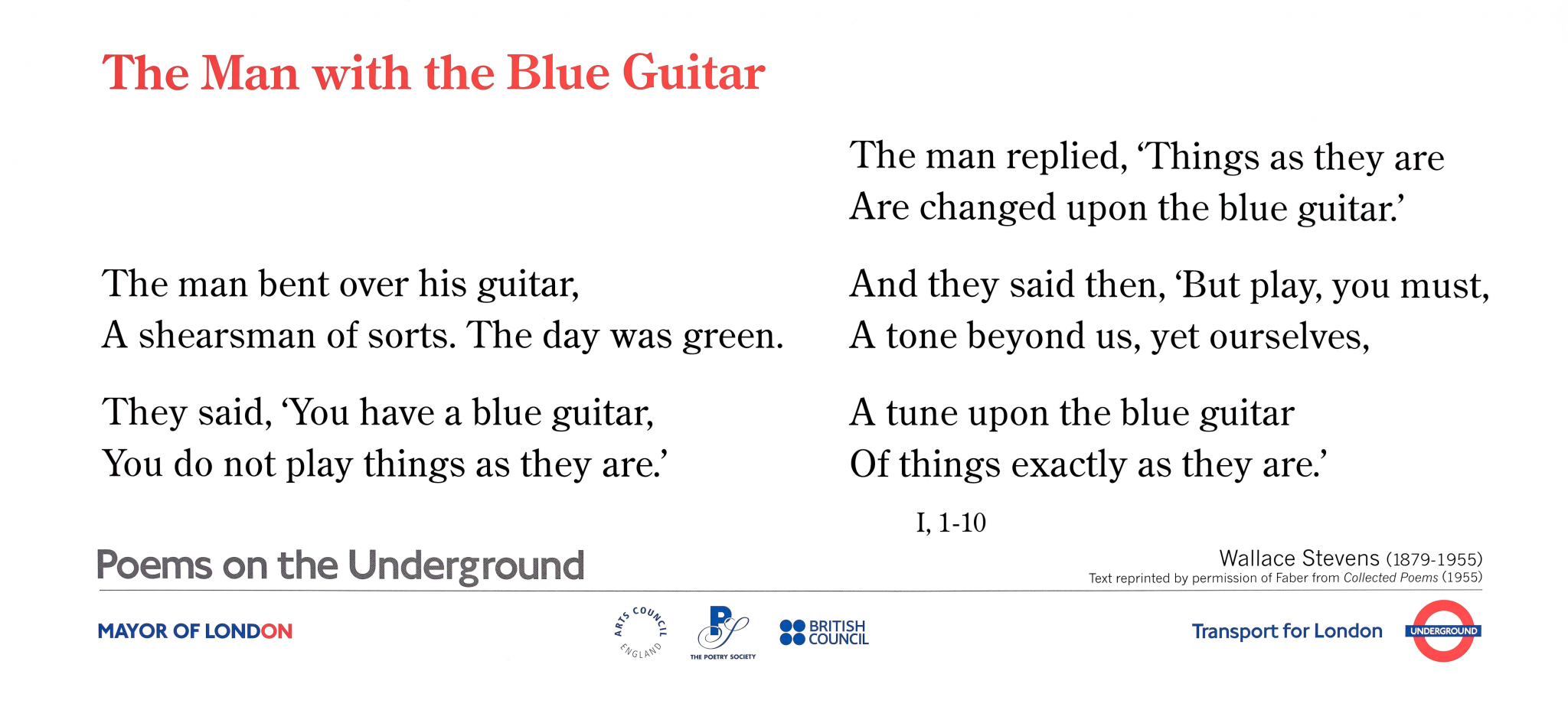

The poem starts with a confrontation. The audience crowds around the guitarist and tells him, "You have a blue guitar, You do not play things as they are."

That’s the hook.

The guitarist replies, "Things as they are / Are changed upon the blue guitar."

Honestly, that’s the whole struggle of being human in two lines. We want the truth. We want "things as they are." But the second we talk about our lives, or take a photo, or write a song, we change the thing we're describing. The "blue" of the guitar represents the imagination. It’s the filter. You can't see the world without your own bias, your own history, and your own "blue" tint getting in the way.

It’s messy.

Think about how we use filters on social media. We take a "real" moment—a sunset, a dinner, a breakup—and we run it through a digital guitar. By the time someone else sees it, it’s not the thing anymore. It’s a version of the thing. Stevens was predicting our digital dysmorphia nearly a century before the first iPhone.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Why Picasso Matters (and Why He Doesn't)

Most critics will tell you Stevens was directly inspired by Picasso’s 1903 painting. While that’s mostly true, Stevens actually downplayed it later in his life. He wasn't trying to do an ekphrastic poem (a poem about a work of art) in the traditional sense. He was using the visual cue of "blue" to talk about the internal world vs. the external world.

In Picasso's Blue Period, the color was about poverty, suffering, and alienation. For Stevens, blue was the color of the mind.

The Conflict of the "To-Be"

The poem is structured in these short, staccato couplets. They feel like a heartbeat. Or a ticking clock.

- The player is trapped by the instrument.

- The audience is trapped by their expectations.

- The "things as they are" remain elusive.

Stevens writes: "I cannot bring a world quite round, / Although I patch it as I can."

He’s admitting he’s a failure. Every artist is. You have this massive, "round" world in your head, but when you try to put it on paper or play it on a string, it comes out "patched." It’s a jagged, imperfect representation. It’s kinda heartbreaking if you think about it too long.

The Politics of the Blue Guitar

We often forget the 1930s were a chaotic, politically charged nightmare. The Great Depression was raking people over the coals. Marxism was the "it" ideology for intellectuals. Many people criticized Stevens for being too "flowery" or "abstract" while people were starving.

They wanted him to play "things as they are"—which, in 1937, meant bread lines and labor strikes.

Stevens countered this in the poem by suggesting that the imagination isn't an escape from reality, but a way to survive it. He writes about a "hero" and a "structure of space." He’s arguing that if we don't have the blue guitar—if we don't have the ability to imagine a different world—then we are just animals reacting to stimuli. We need the fiction to make the facts bearable.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

The Sound of the Poem

The meter is weirdly hypnotic. It’s mostly iambic tetrameter, but he breaks it constantly. It feels like a guy practicing in a room, hitting a wrong note, swearing, and then starting over.

- "A tune beyond us, yet ourselves."

- "The earth, for us, is flat and bare."

- "There are no shadows in our sun."

These lines don't provide answers. They provide moods. Stevens isn't your buddy who gives you advice over a beer; he’s the guy who stares at the beer glass for forty minutes and then explains how the light hitting the foam proves that God is a mathematician.

Common Misconceptions

People often think the "Blue Guitar" is a symbol of sadness because of the "blues" in music. That’s a bit of a reach. While Stevens knew about jazz and blues, his "blue" is more related to the sky or the sea—vast, unreachable, and completely indifferent to human problems.

Another mistake? Thinking the man with the guitar is Stevens himself.

He’s a persona. Stevens was a wealthy man in a grey suit. The man with the guitar is a beggar, a craftsman, and a visionary. He’s the part of Stevens that didn't care about insurance premiums.

What This Means for You Right Now

We live in an era of "The Algorithmic Guitar."

Everything we see is curated. Our reality is being "changed" not by our own imagination, but by lines of code designed to keep us clicking. Stevens’ poem is a call to take back your own guitar. It’s an invitation to realize that you are the one painting your world.

If the world feels "flat and bare," it might be because you’ve stopped playing.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

Real-World Application: The "Blue Guitar" Method

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the news or the sheer "weight" of things as they are, try these three things based on Stevens' philosophy:

- Acknowledge the Filter: Stop pretending you’re objective. You aren't. Your "guitar" is blue. Once you accept that your perspective is a creative act, you stop being a victim of it.

- Embrace the Patchwork: Your life doesn't have to be a "world quite round." It’s okay if it’s patched together. The beauty is in the tension between the dream and the reality.

- Find Your "Tune Beyond Us": Find one thing—a hobby, a book, a specific way you make coffee—that feels like it belongs to your imagination rather than your obligations.

Wallace Stevens died in 1955, still working at the insurance company. He never saw the internet. He never saw how "blue" our world would actually become. But he left us with the realization that the song we play is often more important than the ground we walk on.

The poem concludes not with a grand finale, but with a sense of continuing. It’s about the "wrangling" of the player with his instrument. You don't win the game of life; you just keep playing the tune until the sun goes down.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

To truly grasp the depth of this work, stop reading about it and engage with the source material in a specific way.

First, read Section I and Section XVII aloud. Don't worry about the meaning. Just listen to the percussive "strum" of the words. Notice where your tongue trips—that’s where Stevens is trying to shake you out of your comfort zone.

Second, look at your own "things as they are." Write down a factual description of your day. Then, rewrite it as if you were trying to explain the feeling of that day to a stranger. That gap between the two descriptions? That’s your blue guitar.

Finally, recognize that "the monster" Stevens mentions—the monster of reality—is only defeated when we transform it into something else. Whether you are a coder, a parent, or a literal musician, you are constantly changing the world by perceiving it. Do it with intention. Don't let the guitar play you.