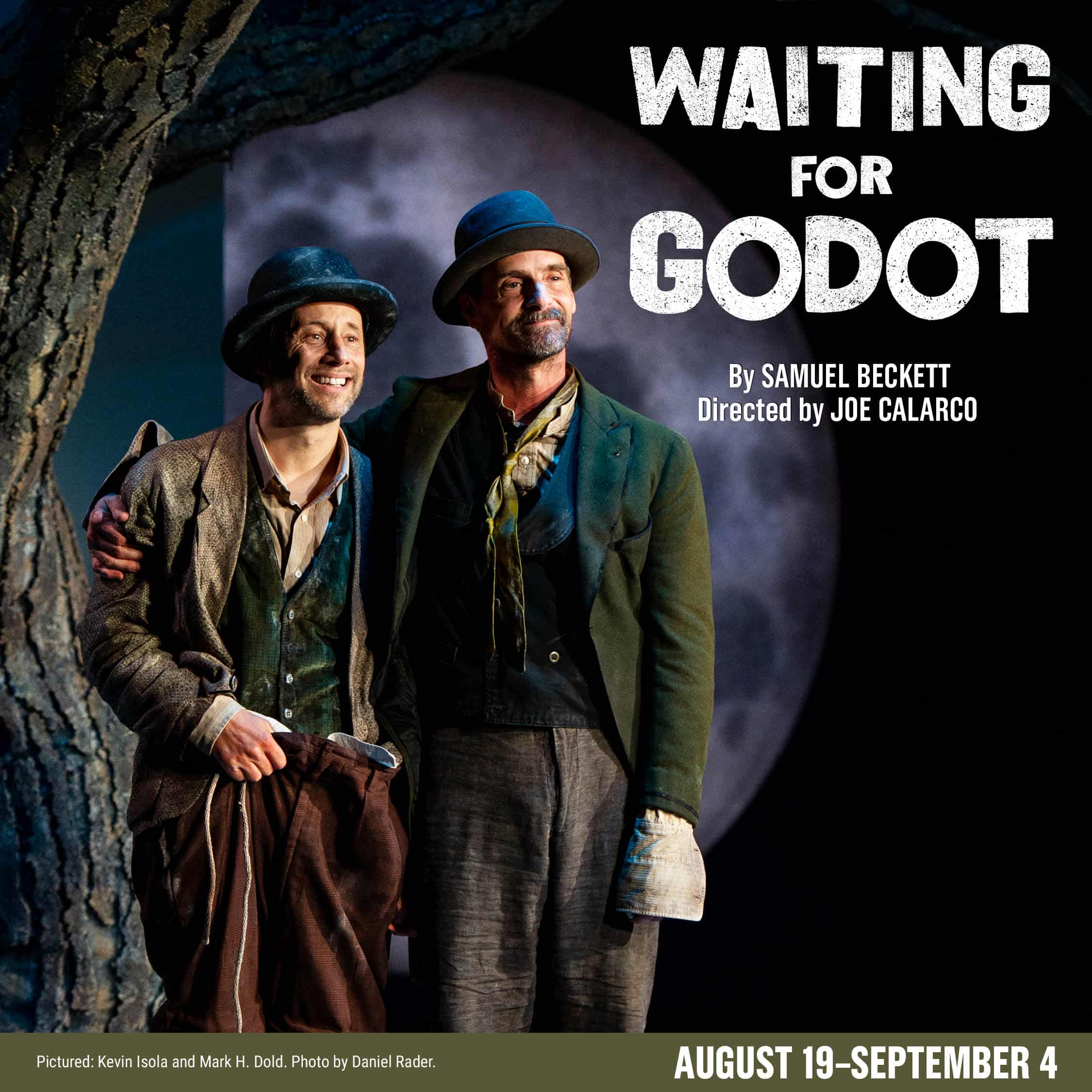

Two guys. One tree. A lot of nothing.

That’s basically the elevator pitch for Samuel Beckett’s most famous work. If you’ve ever sat in a theater and wondered what is Waiting for Godot about, you aren’t alone. Since its premiere in Paris in 1953, audiences have been scratching their heads, walking out in frustration, or weeping in their seats. It’s a play where nothing happens. Twice.

Vladimir and Estragon—or Didi and Gogo, as they call each other—stand by a scrawny, leafless tree on a desolate road. They’re waiting for a man named Godot. They don’t know what he looks like. They aren’t entirely sure if they’re in the right place or if today is even the right day. They consider hanging themselves but realize the tree branch might break. They eat a carrot. They argue about boots.

It sounds tedious. On paper, it is. But on stage? It’s a mirror.

The Plot That Refuses to Be a Plot

Usually, a play follows a linear path. Conflict, rising action, climax, resolution. Beckett tosses that into the trash. In Waiting for Godot, the structure is circular. The first act ends with a boy telling the men that Godot won't come today, but "surely tomorrow." The second act is a distorted reflection of the first. The tree has a few leaves now. A couple of travelers they met earlier, Pozzo and Lucky, return, but they’ve been ravaged by time—one is blind, the other is mute.

The play is essentially a study in "the wait." We spend our lives waiting for something—a promotion, a partner, a sign from the universe, or just the weekend. Beckett strips away the distractions of plot to show the raw, naked experience of existing while time passes.

It’s often funny. Like, actually laugh-out-loud slapstick funny. They trade hats in a dizzying sequence that feels like a Vaudeville routine. They struggle with tight shoes. But the humor is "gallows humor." It’s the kind of laughter that comes when the alternative is screaming into the void.

👉 See also: Candace Bushnell Sex and the City Book: What Most People Get Wrong

Who Is Godot, Anyway?

This is the question that drives everyone crazy. Is Godot God?

Beckett always played coy. He once famously said, "If I knew who Godot was, I would have said so in the play." If you look at the name, "God" is right there at the start, followed by a diminutive French suffix. It’s a "little god." For many, the play represents the silence of the divine in a post-World War II world. The world had just seen the Holocaust and the atomic bomb; people were looking for meaning in a landscape that felt fundamentally broken.

But limiting Godot to a religious figure is a mistake. Godot is whatever keeps you from ending it all. He’s the "tomorrow" that justifies the misery of "today." He is a projection of hope, however misplaced.

The Dynamics of Didi and Gogo

The relationship between the two main characters is the heart of the play. They are a classic comedy duo, but with existential dread.

- Vladimir (Didi): He’s the more intellectual one. He remembers things—or tries to. He’s the one who insists they stay because they have an obligation to Godot. He’s the "head."

- Estragon (Gogo): He’s the "body." He’s focused on his sore feet, his hunger, and the fact that he gets beaten by mysterious strangers every night. He wants to leave, but he can’t.

They are codependent. They hate each other, but they can’t exist without each other. If one left, the other would cease to have a witness to his life. That’s a terrifying thought. If nobody is watching you, do you even exist?

💡 You might also like: Selena Gomez Stars Dance Songs: What Most People Get Wrong

Pozzo and Lucky: Power and Pain

About halfway through each act, the wait is interrupted by Pozzo and Lucky. This is where the play gets dark. Pozzo is a pompous landowner who drives Lucky, his slave, with a rope around his neck.

It’s a brutal depiction of the master-slave dialectic. Pozzo treats Lucky like a beast of burden, but by Act II, Pozzo is blind and completely dependent on Lucky. It suggests that power is a fleeting illusion.

Lucky’s "think" is one of the most famous moments in modern theater. Pozzo commands him to think, and Lucky delivers a several-page-long, unpunctuated monologue that starts like an academic lecture and devolves into a terrifying word salad about a "personal God" who "loves us dearly with some exceptions." It’s the sound of a mind breaking under the weight of a meaningless universe.

Why Does This Play Still Matter?

You might think a 70-year-old play about two guys in a field would be dated. It’s not. In fact, it feels more relevant now than ever.

We live in an age of constant distraction, yet many of us feel like we’re just waiting. Waiting for the climate to collapse, waiting for the next pandemic, waiting for an email. We fill the "dead time" with scrolling, much like Didi and Gogo fill it with word games and hat-swapping.

Beckett was part of the "Theatre of the Absurd." This movement was based on the philosophy of Albert Camus, who argued that humanity has an innate search for meaning, but the universe is stubbornly silent. The "absurd" is the conflict between those two things.

When you ask what is Waiting for Godot about, the answer is: it's about the courage to keep going when there is no reason to. The play ends with one of the most famous stage directions in history:

VLADIMIR: Well? Shall we go?

ESTRAGON: Yes, let's go.

They do not move.

That is the human condition in four words. We know we should move. We say we will move. But we stay.

Common Misconceptions

People often think the play is a puzzle to be "solved." They think if they find the right clue, they'll unlock the secret meaning.

There is no secret.

Beckett was a minimalist. He wanted the audience to feel the boredom and the anxiety. If you’re bored while watching it, you’re actually having the "correct" experience. It’s supposed to be uncomfortable. It’s supposed to make you look at your own life and ask what you’re waiting for and why you haven’t started living yet.

Another myth is that it’s purely depressing. It’s actually quite tender. These two men have been together for fifty years. They help each other. They share food. In a world that is empty and cold, their companionship is the only thing that is "real."

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're looking to dive deeper into Beckett's world or just want to sound smarter at your next dinner party, here’s how to approach the "Godot" experience:

- Watch a production before reading the script. This isn't Shakespeare; the stage directions and the silence are just as important as the words. Look for the filmed version starring Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen—their real-life friendship brings a level of pathos to Didi and Gogo that is hard to match.

- Focus on the "Small" things. Don't get bogged down in the "God" metaphor. Pay attention to the boots, the hats, and the carrots. Beckett uses the physical world to ground the lofty philosophical questions.

- Identify your own "Godot." Ask yourself: "What am I waiting for that is stopping me from acting today?" The play is a warning against passivity.

- Embrace the Silence. In our world of constant noise, Beckett’s use of pauses is revolutionary. Try to sit in silence for five minutes today. See how long it takes for your brain to start "hat-swapping" to avoid the discomfort of just being.

The brilliance of the play isn't in what Godot represents, but in what the characters do while he's gone. We are all waiting. The question is how we treat the people standing on the road next to us while we do.