You’re petting your dog, your fingers slide through that soft fur behind their ears, and then you feel it. A bump. Your heart sinks a little. Is it a skin tag? A mole? Or is it a parasite currently draining your best friend’s blood? Honestly, most people panic and grab the tweezers immediately, which is usually the first mistake.

Looking at pics of ticks on dogs online can actually be more confusing than helpful because ticks don't always look like the classic "bug" you see in textbooks. They change. They morph. A hungry tick looks like a tiny, flat poppy seed, but a fed one? That looks like a gross, silvery-grey grape or a literal bean stuck to your dog’s skin. It’s weirdly deceptive.

What you’re actually seeing: The anatomy of a hitchhiker

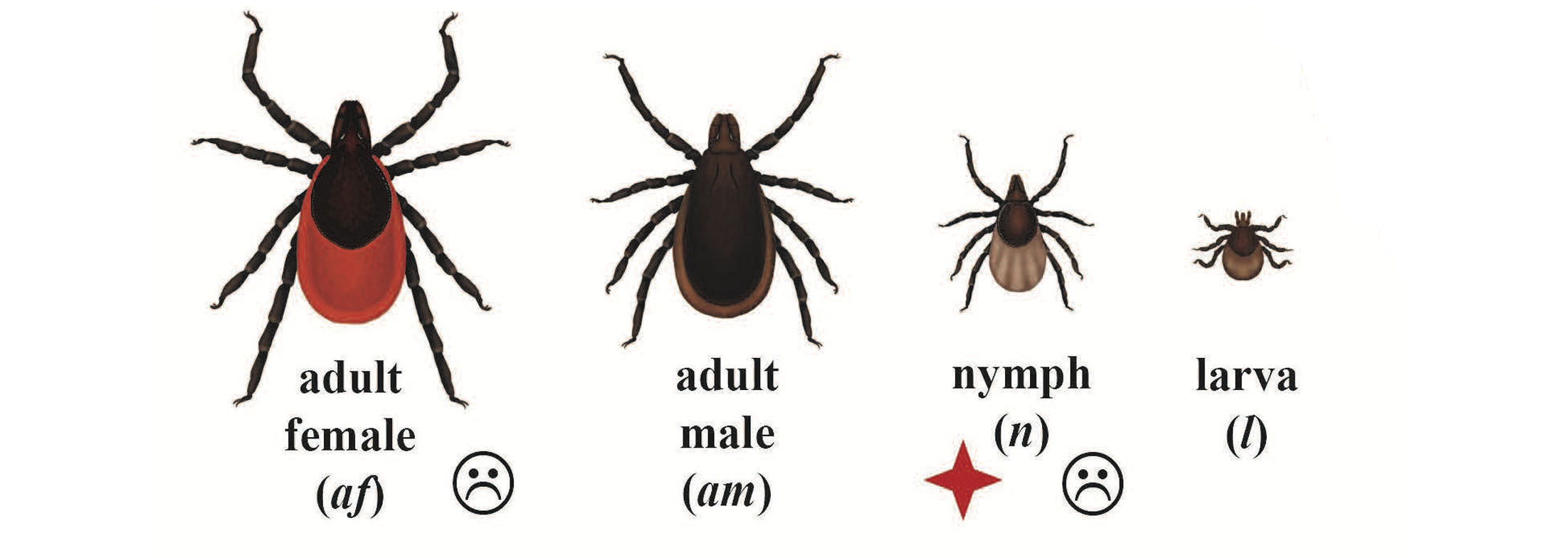

When you search for pics of ticks on dogs, you’ll notice a massive variety in color and size. This isn't just because there are different species—though there are—but because of where the tick is in its life cycle. A larval tick is nearly microscopic. You probably won't even see it unless you're looking with a magnifying glass. By the time they reach the nymph or adult stage, they become the "lumps" we dread.

Look closely at the "bump" on your dog. If it’s a tick, you won't see a head. Ticks bury their mouthparts deep into the dermis. What you are seeing is the abdomen. If the tick has been there for a few days, it becomes "engorged." This is when it looks like a smooth, shiny pebble. It might be light brown, grayish-blue, or even a sickly olive green.

The legs are the giveaway. If you can move the body slightly to the side with a cotton swab, you might see tiny, spindly legs right at the base where it meets the skin. Skin tags don't have legs. Warts don't have legs.

The Great Pretenders: Is it a tick or something else?

I’ve seen dozens of frantic owners rush to the vet only to find out they were trying to pull off a nipple. It happens way more than you’d think. Dogs have nipples in two rows along their belly, and on some breeds, they can be dark or oddly shaped. Before you pull, check for symmetry. If there’s an identical "tick" on the other side of the belly, leave it alone.

👉 See also: Finding the University of Arizona Address: It Is Not as Simple as You Think

Then there are sebaceous cysts. These are common in older dogs, especially Cockers or Labradors. They feel firm, but they are part of the skin. A tick feels like something attached to the skin, almost like a piece of jewelry that shouldn't be there. If you see a "tick" that is the exact same color as your dog’s skin and has hair growing out of it, it’s a skin growth. Ticks don't grow hair.

Identifying species by the way they look

Not all ticks carry the same risks. While you’re scrolling through pics of ticks on dogs, try to match the markings on the "scutum"—that’s the hard shield right behind the mouthparts.

- Deer Ticks (Black-legged Ticks): These are the ones everyone scares you about because of Lyme disease. They are tiny. Even as adults, they’re often no bigger than a sesame seed. They have dark legs and a reddish-orange body.

- American Dog Ticks: These are beefier. They often have white or silver markings on their backs. They’re famous for transmitting Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

- Lone Star Ticks: These are easy to spot if you get a good look. The females have a single white dot right in the middle of their back.

The University of Rhode Island’s "TickEncounter" resource is basically the gold standard for this. They have high-resolution photos that show the scale of these bugs next to a penny, which is a lot more helpful than a zoomed-in macro shot that makes a tick look like a monster from a sci-fi movie.

The danger of the "Red Halo"

If you find a tick and pull it off, look at the skin afterward. A little redness is normal. It's a bite, after all. Your dog’s immune system is reacting to the tick’s saliva, which contains anticoagulants and numbing agents. It’s basically a tiny inflammatory cocktail.

However, if you see a widening red circle—the classic "bullseye"—that’s a massive red flag. While dogs don't always show the bullseye rash as clearly as humans do because of their fur, localized swelling that turns into a crusty sore or an abscess needs a vet’s eyes.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

Sometimes, the head breaks off during removal. People freak out about this. They think the head will "travel" to the heart or something equally terrifying. It won't. The dog’s body will usually treat it like a splinter and push it out eventually. The real risk is the pathogens already injected into the bloodstream during the feed.

Why "Wait and See" is a bad strategy

Ticks don't just take blood; they swap fluids. The longer a tick stays attached, the higher the "viral load" or bacterial transmission risk. For Lyme disease, the tick usually needs to be attached for 24 to 48 hours. But for things like Anaplasmosis or certain viruses, the window can be much shorter.

If you find a tick that is fully engorged—meaning it looks like a fat, grey bean—it has been there for a while. It’s been feasting for at least 3 to 7 days. This is the scenario where you want to keep that tick. Drop it in a small jar of rubbing alcohol or a Ziploc bag. If your dog starts limping, acting lethargic, or loses their appetite two weeks from now, your vet can actually test that specific tick or at least know exactly what your dog was exposed to.

Real-world check: Where to look on your dog

You won't find them just sitting on the back. Ticks love "high-traffic" areas where the skin is thin and the blood vessels are close to the surface. Check these spots every single time you come back from a walk:

- Between the toes (a classic hiding spot).

- Inside the ear flaps.

- Under the collar.

- The "armpits" and groin area.

- Under the tail.

Basically, if it’s a dark, warm crevice, a tick is probably trying to move in.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

Proper removal without the myths

Forget the matches. Forget the peppermint oil or the nail polish. These "home remedies" are actually dangerous. When you irritate a tick with heat or chemicals, it often vomits its stomach contents back into your dog. That’s exactly how diseases are spread. You’re essentially fast-tracking the infection.

Use fine-tipped tweezers. Grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible—you want to grab the head, not the body. Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don't jerk it. If you squeeze the big, fat body (the abdomen), you’re essentially acting like a syringe, pushing the fluids into your dog.

Once it’s out, clean the area with isopropyl alcohol. Wash your hands. Don't squish the tick with your fingers; their fluids can carry diseases that infect humans through tiny cuts in the skin.

Prevention is cheaper than the cure

Honestly, looking at pics of ticks on dogs is a reactive move. You want to be proactive. Modern preventatives like Bravecto, NexGard, or Simparica Trio have changed the game. These are oral chews that make your dog’s blood toxic to ticks. When a tick bites, it dies before it can transmit most diseases.

There are also Seresto collars, which work well if they are fitted tightly enough to make skin contact. If the collar is loose and just sitting on the fur, it’s not doing much.

But remember: no preventative is 100% effective. A tick might still hitch a ride on your dog’s fur, come into your house, and then decide you look like a better snack. This is why "tick checks" are a daily necessity for hikers and suburban dog owners alike.

Actionable Next Steps for Dog Owners

- Perform a "finger-comb" check: After every walk in tall grass or wooded areas, run your hands firmly over your dog's entire body. You are feeling for small, hard bumps that weren't there yesterday.

- Create a Tick Kit: Keep a pair of fine-tipped tweezers, a small vial of alcohol, and some antiseptic wipes in a dedicated spot. Finding a tick at 11 PM is stressful; hunting for tools makes it worse.

- Check the "Hidden" Spots: Use a flashlight to look inside your dog's ears and between their paw pads. Ticks are experts at staying out of sight.

- Consult your vet about local risks: Tick populations vary wildly by geography. In some areas, Lyme is the big threat; in others, it’s Babesiosis or Ehrlichia. Knowing what’s in your backyard helps you know what symptoms to watch for.

- Don't wait for symptoms: If you removed a heavily engorged tick, mark your calendar. Watch for lethargy, joint pain, or fever over the next 14 days. If the dog seems "off," get a 4DX snap test at the clinic.

Managing ticks is a bit gross, but it's a standard part of dog ownership. Being able to distinguish between a harmless skin tag and a parasitic tick by knowing what to look for in those photos saves a lot of unnecessary vet bills—and a lot of unnecessary stress for your pup.