You're standing in the grocery aisle, squinting at a yogurt container. It says 150 calories. But if you've ever fallen down a science rabbit hole or traveled across Europe, you've probably seen the term "kcal" and wondered if you're actually eating way more than you thought. It's confusing. Honestly, the way we talk about energy in food is a mess of historical accidents and linguistic laziness.

So, let's get the math out of the way first. There are exactly 1,000 small calories in a kilocalorie.

Wait. Did I just say small calories? Yeah. That's where the headache begins. In the world of science and nutrition, we use the same word—calorie—to mean two completely different things depending on whether the "C" is capitalized. It’s a bit ridiculous.

The "Big C" vs. "Small c" Confusion

Technically, a kilocalorie (kcal) is what we almost always mean when we talk about diet and exercise. If your fitness tracker says you burned 400 calories on the treadmill, it actually means 400 kilocalories.

In a laboratory setting, a "small calorie" (cal) is the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of one gram of water by $1^\circ C$. But humans are big. We need a lot of energy. Measuring human metabolism in small calories would involve numbers so massive they’d be impossible to read on a Snickers bar. Imagine seeing "250,000 calories" on a snack. You’d drop the wrapper in horror. To keep things manageable, the nutrition industry uses the "Large Calorie" (Cal), which is synonymous with the kilocalorie.

One kcal equals 1,000 small calories. That's the conversion.

It’s just 1,000.

Most people don't realize that when they ask how many calories in a kilocalorie, they are usually asking for a translation between "science speak" and "food label speak." In the United States, the FDA allows companies to just use the word "Calories" (with a capital C) to represent kilocalories. Meanwhile, in much of the European Union, Australia, and the UK, you’ll see "kcal" written explicitly on the back of the pack. They are the exact same thing.

🔗 Read more: Images of the Mitochondria: Why Most Diagrams are Kinda Wrong

Why Do We Even Use This Metric?

We owe this system to a 19th-century German chemist named Wilbur Atwater. He was the guy who decided to stick food into a device called a bomb calorimeter. He basically burned food to see how much heat it released. It's a bit of a violent way to think about a sandwich, but it worked.

Atwater’s research led to the "Atwater Factors," which are the standard values we still use today:

- Protein: 4 kcal per gram

- Carbohydrates: 4 kcal per gram

- Fats: 9 kcal per gram

- Alcohol: 7 kcal per gram

When you look at a label and see 10 grams of fat, you’re looking at 90 kilocalories of energy. The math is surprisingly consistent, though some modern nutritionists argue it’s a bit too simple.

The Flaw in the Math

Not all kilocalories are created equal once they enter your "internal furnace." Your body isn't a literal bomb calorimeter. It doesn't just burn everything to ash. For instance, your body spends a lot more energy trying to process protein than it does processing simple sugars. This is known as the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF).

If you eat 100 kilocalories of egg whites, your body might only "keep" 70 of them because the digestive process is so work-intensive. If you eat 100 kilocalories of pure sugar, your body keeps nearly all of them. So, while the answer to how many calories in a kilocalorie is always 1,000, the "value" of that kilocalorie to your waistline varies wildly.

The Global "kcal" vs "kJ" Rivalry

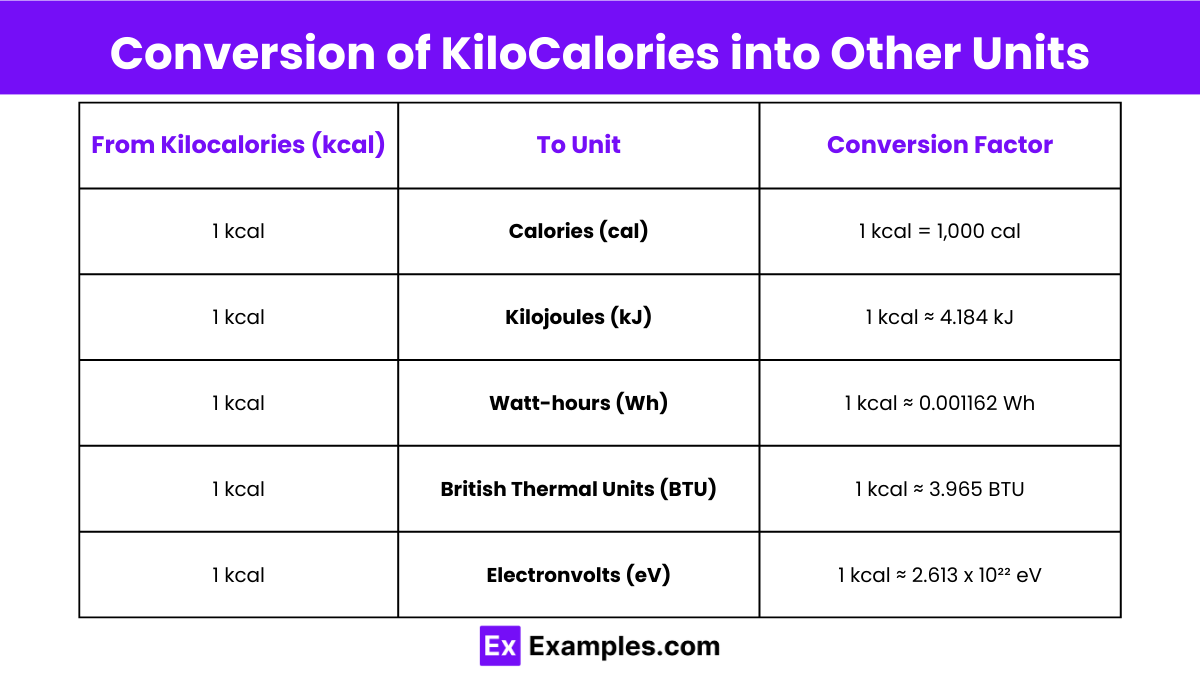

If you travel, you’ll see another unit: the Kilojoule (kJ). This is the SI unit of energy. To convert a kilocalorie to a kilojoule, you multiply by 4.18.

Most people hate this.

💡 You might also like: How to Hit Rear Delts with Dumbbells: Why Your Back Is Stealing the Gains

Doing mental math at a French bistro to figure out if that croissant is 1,200 kilojoules or something you can actually afford to eat is a nightmare. But it’s the standard in the scientific community. One kilocalorie is the energy required to raise one kilogram of water by $1^\circ C$. One kilojoule is more about mechanical work.

Real-World Examples of Energy Density

Let's put these kilocalories into perspective.

A single gallon of gasoline contains about 31,000 kilocalories. If a human could drink gas (please don't), that one gallon would fuel an average adult for about two weeks. It shows how incredibly dense energy can be.

On the flip side, consider celery. It’s mostly water and fiber. You could eat a mountain of it and barely hit 100 kilocalories. This is the "energy density" concept that nutritionists like Dr. Barbara Rolls have championed for years. By focusing on the kilocalories per gram of food, you can eat a higher volume of food while consuming fewer total kilocalories.

Does the Label Lie?

Kinda.

The FDA actually allows a 20% margin of error on nutrition labels. That means if a bag of chips says it has 200 kilocalories, it could legally have 240. Over the course of a day, those little discrepancies can add up. This is why people who track their intake with extreme precision often find they aren't losing weight as fast as the math suggests. The math is an estimate, not a universal law of physics.

Why Knowing the Difference Matters for Your Health

If you're using a recipe from a European website, it might list "kcal" and you might panic thinking it's a different unit. It isn't. If you're looking at a scientific study about "calories," check the lowercase 'c'. If they are talking about "100 calories," they are talking about a tiny, microscopic amount of energy.

📖 Related: How to get over a sore throat fast: What actually works when your neck feels like glass

Understanding that 1 kilocalorie = 1,000 calories is mainly useful for two types of people:

- Students taking a chemistry or biology quiz.

- People curious about why their European snacks look so "high calorie" at first glance.

Summary of Energy Units

To keep it straight:

- 1 calorie (cal): The tiny one. Energy for 1 gram of water.

- 1 kilocalorie (kcal): The one on your food label. 1,000 small calories.

- 1 Calorie (capital C): The American way of writing kilocalorie.

- 1 Kilojoule (kJ): 0.239 kilocalories.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Calories

Stop stressing about the "k." In 99% of life, "calorie" and "kilocalorie" are used interchangeably.

If you want to use this information to actually improve your health, start by looking at energy density rather than just the raw number of kilocalories. Swap high-density foods (oils, sugars) for low-density ones (leafy greens, watery fruits).

Check the "Serving Size" first. This is the biggest trap. A bottle of soda might list 100 kilocalories, but the bottle contains 2.5 servings. Suddenly, that "100" is actually 250.

Always round up. Since labels can be off by 20%, assuming your meal has a few more kilocalories than listed is a safer bet for weight management.

Don't ignore the kilojoule if you're abroad. Just remember the "rule of 4." Divide the kJ by 4 to get a rough estimate of the kilocalories. It's close enough for a vacation.

Focus on protein and fiber. These nutrients require more energy to burn, meaning not all 1,000 calories in that kilocalorie will actually end up stored as fat.

Understand that your metabolism isn't a calculator. Sleep, stress, and gut microbiome play massive roles in how you process these units of energy. Use the numbers as a guide, not an absolute truth.