If you’re hanging out in a high-energy physics lab or just messing around with electromagnetic hobbyist gear, you’ve probably wondered what happens when extreme energy hits soft metal. Can a plasma accelerator pop lead? Honestly, the answer depends entirely on what you mean by "pop." If you mean making it explode like a firecracker, yeah, it definitely can. But the physics behind it is way cooler than just a simple pop.

Lead is weird. It’s heavy, it’s soft, and it has a remarkably low melting point of about 327°C. When you introduce a plasma accelerator—a device that uses ionized gas to accelerate particles to insane speeds—you aren’t just heating the lead. You’re hitting it with a localized shock of energy that can turn solid metal into a pressurized gas almost instantly.

💡 You might also like: I'm Not a Robot 2024: Why CAPTCHAs Are Getting Weirder and What It Means for You

The Mechanics of Making Lead Pop

Plasma accelerators, like those researched at CERN or SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, are usually built to move electrons or protons. But when that focused beam or the resulting plasma wakefield hits a physical target like a lead brick, things get messy.

The "pop" you’re looking for is basically a phase transition on steroids. When the energy density is high enough, the lead doesn't just melt and drip. It undergoes ablation. The surface layers vaporize so fast they create a recoil pressure. This sends a shockwave through the rest of the lead. If the lead is thin or shaped a certain way, that internal pressure has nowhere to go but out.

Pop.

Actually, it’s more of a metallic "crack." You’ve probably seen videos of "exploding" wires in physics demos. That’s a similar concept. You dump a massive amount of electrical energy into a conductor, and the magnetic fields and heat pressure literally tear the metal apart. With a plasma accelerator, you’re doing this with even more precision and much higher energy scales.

Why Lead is the Perfect Victim

Physics researchers actually use lead and other heavy metals like tungsten as "targets" in beam dumps and converters. Because lead is so dense ($11.34 \text{ g/cm}^3$), it’s great at stopping particles. But that’s also its downfall.

- Low Boiling Point: Lead boils at around 1,749°C. In the world of plasma physics, that's nothing. A plasma wakefield can reach temperatures that make the surface of the sun look like a freezer.

- Thermal Expansion: Lead expands when it gets hot. Rapid expansion in a confined space equals an explosion.

- Softness: Unlike steel, which might deform slowly, lead is "malleable." It flows. When hit by a plasma-induced shockwave, it behaves more like a liquid than a solid, leading to spectacular structural failure.

Real World Examples: From Labs to Railguns

People often confuse plasma accelerators with plasma cutters or railguns. They’re cousins, but not siblings. A plasma cutter uses a stream of ionized gas to melt through lead like butter. That’s not a "pop," that's just a clean slice.

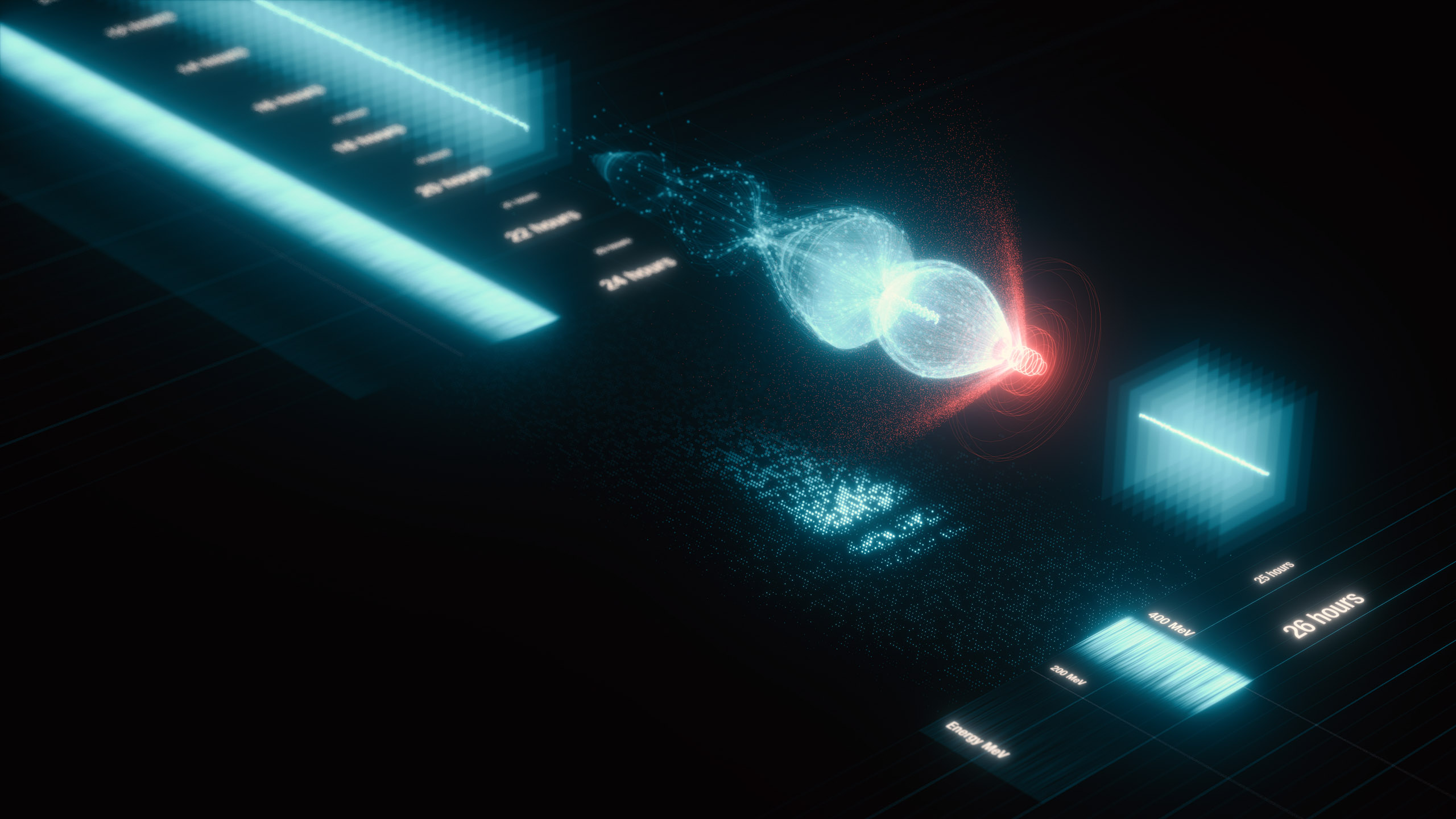

However, in the world of Advanced Wakefield Experiment (AWAKE) at CERN, scientists use plasma to accelerate particles over short distances. If a lead shield were placed directly in the path of a high-intensity pulsed beam, the localized energy deposition would cause a "Coulomb explosion."

Basically, the electrons are stripped away so fast that the remaining positive ions in the lead suddenly find themselves next to each other. They hate that. They repel each other with such force that the metal literally flies apart at the atomic level. It’s the ultimate "pop."

Is this something you can do at home?

Short answer: No.

Long answer: Definitely not, and please don't try.

Plasma accelerators require high-vacuum chambers, massive power supplies, and usually a lot of shielding to keep the X-rays from frying your DNA. If you tried to "pop" lead with a DIY plasma setup, you'd likely just melt your garage's circuit breaker or end up with a puddle of lead fumes. Lead vapor is incredibly toxic. Breathing in "popped" lead is a one-way ticket to a very bad time at the hospital.

The Surprise: Lead as a Shield

Interestingly, even though a plasma accelerator can pop lead, we still use lead to protect ourselves from the accelerators. It’s a bit of a paradox. In most facilities, the lead isn't the target; it’s the wall. As long as the beam is contained and steered by magnets, the lead stays solid and does its job of absorbing stray radiation.

💡 You might also like: Loftie Smart Alarm Clocks Explained: Why Your Phone is Ruining Your Morning

But if a magnet fails? If the beam wanders? That’s when you get what physicists call a "target failure." It's a polite way of saying the equipment exploded.

What Happens at the Microscopic Level?

When we talk about a plasma accelerator popping lead, we’re looking at Hydrodynamic Expansion.

- Energy Deposition: The plasma or particle beam hits the lead in a matter of nanoseconds or even picoseconds.

- Isochoric Heating: The lead gets hot so fast that it doesn't have time to expand yet. The pressure spikes to millions of atmospheres.

- The Blast: The pressure overcomes the metallic bonds holding the lead together.

- Fragmentation: The lead shatters into a fine mist of droplets and vapor.

This isn't just theory. Researchers at the Laser-Dielectric Accelerator projects have looked at how different materials handle these stresses. Lead is consistently one of the easiest to "disrupt" because it lacks the lattice strength of something like diamond or even copper.

The Role of Plasma Density

Not all plasma is created equal. A "cold" plasma might just sit there and glow purple. To pop lead, you need high-density, high-temperature plasma.

In experiments involving Laser-Produced Plasmas (LPP), a high-power laser hits a target to create a plasma plume. If that plume is directed at a secondary lead target, the kinetic energy of the ions in the plasma can be enough to create physical pitting and "spallation"—where chunks of the back of the lead fly off even if the front wasn't fully pierced.

Why This Actually Matters for the Future

You might think "popping lead" is just a destructive curiosity. It's not. Understanding how materials fail under plasma stress is key to building better nuclear fusion reactors.

In a fusion device like ITER, the inner walls are constantly bombarded by high-energy particles. While they use tungsten instead of lead because it's tougher, the physics of "popping" and melting is the biggest hurdle to clean energy. If we can't stop the plasma from destroying the container, we can't keep the "star" alive.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're fascinated by the intersection of plasma and heavy metals, here's how to dive deeper without blowing up your kitchen:

👉 See also: Tomlinson Holman Explained: Why the Man Behind THX is the Most Important Name in Audio

- Study Material Science: Look into "Spallation" and "Ablation." These are the technical terms for how metals fail under high-energy impacts.

- Follow Research Labs: Check out the latest briefings from Brookhaven National Laboratory or DESY in Germany. They often post high-speed footage of beam-target interactions.

- Understand the Limits: Lead is a great beginner's topic because it's so "weak" in the face of plasma. Once you understand lead, look into how plasma interacts with Graphene or Carbon Nanotubes, which are way more resilient.

- Safety First: If you are working with any kind of plasma or high-voltage hobbyist gear, always ensure you have adequate ventilation for heavy metal fumes and proper eye protection against UV and X-ray emissions.

Essentially, a plasma accelerator can pop lead with ease, turning a dull grey brick into a spray of molten droplets and toxic gas in the blink of an eye. It’s a violent, beautiful display of what happens when the fourth state of matter meets the heavy elements of the periodic table.

To see this in action, look for "High-speed imaging of laser-matter interaction" on academic databases. You'll see that "popping" is actually a complex dance of pressure, heat, and electromagnetic force. It's a reminder that under the right conditions, even the heaviest, most solid-seeming objects are just temporary arrangements of atoms waiting for enough energy to break free.