You’ve probably heard it in a church, a movie, or maybe a high school choir concert. The melody is haunting. It stays with you. But the wade in the water slave song isn't just a piece of music. It’s a survival manual. Honestly, when we talk about the American Spiritual, we often treat it as "folk art" and move on. That’s a mistake. We’re talking about a sophisticated, multi-layered communication system used by people who were legally forbidden from reading or writing.

It was a code.

Think about the sheer guts it took to sing instructions for a prison break right in front of the guards. That is exactly what was happening in the fields of the American South. While the plantation owners heard a song about the Bible, the enslaved people heard a GPS notification.

What the Lyrics Actually Meant

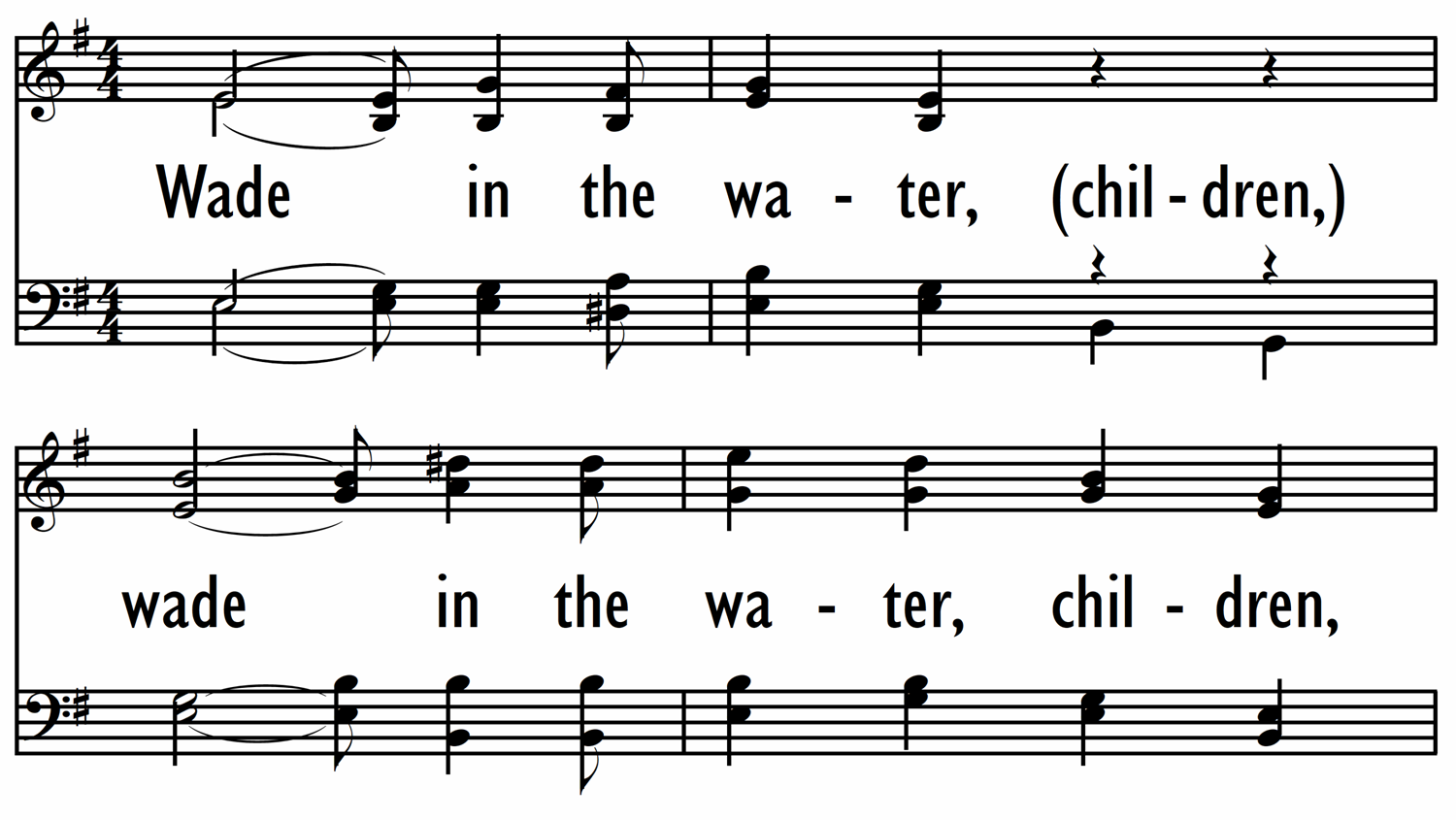

The chorus is the part everyone knows. "Wade in the water, wade in the water children / Wade in the water, God’s gonna trouble the water." On the surface? It’s a reference to the Book of John, specifically the pool at Bethesda where an angel would "trouble" the water to provide healing.

But if you’re running for your life through the Maryland woods in 1850, you aren't thinking about ancient Bethesda. You’re thinking about bloodhounds.

Slaves used the wade in the water slave song to tell runaway groups to get off the dry trails. If you stay on the dirt, the dogs can track your scent for miles. If you get into the stream—if you "wade in the water"—that scent trail vanishes. The water "troubles" the scent. It’s a tactical maneuver disguised as a hymn. Harriet Tubman is widely believed to have used this specific spiritual to signal to those she was leading toward freedom. It was a warning: the slave catchers are close, their dogs are out, so get into the river now.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The Jordan River and the Ohio River

In these songs, "The River Jordan" was rarely just a biblical metaphor for crossing into heaven. Usually, it meant the Ohio River. Crossing the Ohio meant hitting free soil. When the song mentions "marching to Canaan," it’s not talking about the Promised Land in the Middle East. It’s talking about Canada.

Harriet Tubman’s Musical Toolkit

We have to look at the work of experts like Arthur C. Jones, who founded The Spirituals Project. He’s spent years documenting how these songs functioned as "map songs." It wasn't just "Wade in the Water." You had "Follow the Drinking Gourd," which was a literal map of the Big Dipper pointing north. You had "Steal Away," which signaled an upcoming meeting or an imminent escape.

The wade in the water slave song was unique because it was an active instruction.

Some historians argue about the "Map Song" theory. They say there isn't enough written evidence from the 1800s to prove every song was a code. Well, yeah. That’s the point of a secret code. You don’t write it down when the penalty for being caught is death. But the oral tradition—the accounts passed down through Black families and recorded by researchers like Sarah Bradford (who interviewed Tubman)—makes the connection pretty undeniable.

The Sound of Resistance

Listen to the rhythm. It’s steady. It’s a walking pace.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Music was one of the few things the enslaved were allowed to keep. It was a loophole. A person singing was seen as a "happy slave" by the white overseers. It was a psychological shield. While the lyrics provided the "how-to" of the escape, the act of singing together provided the "why." It kept the group synchronized. It kept the fear at bay.

The song also mentions "See those dressed in white / Well, it looks like the Israelites." Some scholars suggest "dressed in white" referred to the hidden faces of those helping on the Underground Railroad, or perhaps a way to identify friends in the dark. Others think it was a way to remind the escaped that they weren't alone—that they were part of an ancient story of liberation.

Why This Song Refuses to Die

It’s been covered by everyone. The Staple Singers. Alvin Ailey’s dance troupe. Ramsey Lewis.

It transitioned from the fields to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Why? Because the core message didn't change. It’s still about navigating through a "troubled" environment to find safety. When protestors in Birmingham or Selma sang these songs, they were tapping into a 150-year-old reservoir of defiance.

There’s a common misconception that spirituals were "sorrow songs" about being passive and waiting for God to fix things. No. They were about agency. They were about taking the risk to step into the cold, dangerous water because the status quo was even worse.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Modern Interpretations

If you listen to the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ versions from the late 19th century, you hear a very polished, choral sound. They were the ones who first brought this music to a global audience. But if you hear it sung in a small AME church in the South today, it’s grittier. It’s more percussive. You can hear the mud and the reeds and the fear of the lantern light in the distance.

How to Engage with This History Today

Understanding the wade in the water slave song requires more than just listening to a Spotify track. It’s about recognizing the intelligence and the strategic brilliance of the people who composed it.

- Visit the sites: If you’re ever in Cincinnati, go to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. They have incredible exhibits on how music functioned as a tool for liberation.

- Study the Gullah Geechee culture: The sea islands of South Carolina and Georgia have preserved the most authentic versions of these spirituals. The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor is a vital resource for anyone wanting to hear the "source code" of American music.

- Read the primary accounts: Check out Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman by Sarah Bradford. It’s one of the few contemporary accounts that gives us a window into how Tubman actually operated.

The next time this song comes on, don't just think about the melody. Think about the person standing at the edge of a dark river, hearing those lyrics, and deciding to jump in. The water was cold. The dogs were loud. But the song told them exactly what to do.

To truly honor this history, look for the "hidden maps" in the art you consume today. Creative resistance hasn't disappeared; it has just changed its tune. Support organizations like the Spirituals Council or local Black history archives that keep these oral traditions alive and verified. Explore the works of Bernice Johnson Reagon, who founded Sweet Honey in the Rock; her research into the "lining out" style of these songs reveals how they were taught and memorized instantly by large groups. Digging into the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center archives will give you access to raw, unproduced field recordings that capture the soul of this music far better than any modern studio recording ever could.