You’re sitting there, probably scrolling or leaning on one hand, and you decide to scratch your nose. That's a choice. You thought it, your brain sent a signal, and your arm moved. But while you were doing that, your heart thumped about eighty times, your diaphragm pulled air into your lungs, and your stomach started churning whatever you had for lunch. You didn’t ask for any of that. It just happened. This weird, constant friction between what we control and what we don't is the whole story of voluntary vs involuntary muscles.

Honestly, it’s a miracle we don't have to remind ourselves to breathe. If we had to manually manage every muscle contraction, we’d be dead in minutes because we’d simply forget to keep the engine running. Your body is basically split into two operating systems: the one where you're the pilot, and the one that's on a permanent, unbreakable autopilot.

The Basic Breakdown of Muscle Types

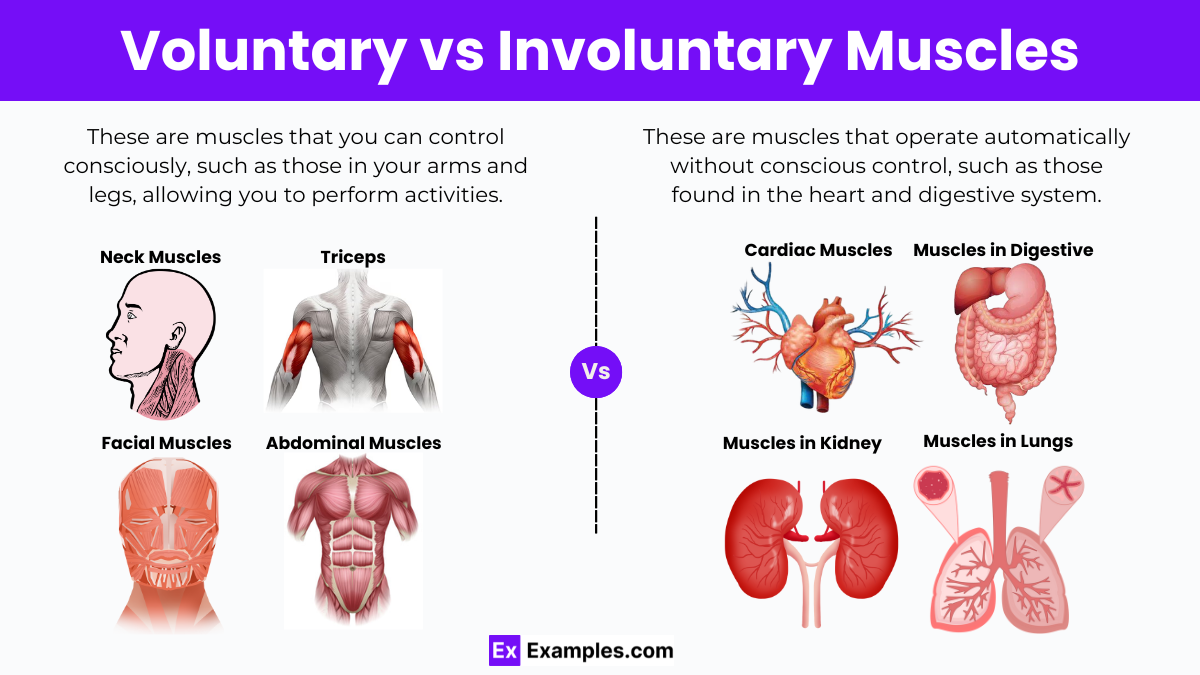

To understand how this works, we have to look at the three types of muscle tissue in the human body. It isn't just "active" and "passive." Scientists generally categorize them as skeletal, smooth, and cardiac.

Skeletal muscles are the ones you usually think about when you hit the gym. They're the bicep curls, the squats, and the smile you fake when you see someone you sort of recognize at the grocery store. These are your voluntary muscles. They are striated, meaning if you looked at them under a microscope, they’d look like they have stripes or bands. They attach to your bones via tendons. When they contract, they pull on the bone, and you move. Simple.

Then you have smooth muscles. These are the wallflowers of the anatomy world. They line your internal organs—think intestines, bladder, and blood vessels. They don't have those stripes, which is why they're called "smooth." These are involuntary. You can't "flex" your esophagus to make your dinner go down faster. It happens through a process called peristalsis, a rhythmic wave of contraction that you have zero say in.

Finally, there’s cardiac muscle. This is the outlier. It’s striated like skeletal muscle because it needs to be incredibly strong, but it’s involuntary like smooth muscle. Your heart has its own internal pacemaker. It’s the only muscle in the body that never, ever gets a full day off until the very end.

Voluntary vs Involuntary Muscles: The Control Gap

The real difference lies in the nervous system. Voluntary muscles are hooked up to the Somatic Nervous System. This is the part of your brain that processes sensory info and carries out "purposeful" movement. When you want to pick up a coffee mug, your motor cortex fires off a signal that travels down the spinal cord and hits the specific motor units in your hand and arm.

Involuntary muscles, however, are governed by the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). The ANS is split into two famous branches: the sympathetic (fight or flight) and the parasympathetic (rest and digest).

Think about it this way.

When you’re scared, your heart rate spikes. You didn't tell it to do that. Your pupils dilate to let in more light so you can see the "threat" better. Again, not your call. The ANS is constantly scanning the environment and your internal chemistry—checking carbon dioxide levels in the blood or the stretch of your stomach—and adjusting muscle tension accordingly. It's a 24/7 surveillance state inside your own ribs.

The "Gray Area" Muscles

Sometimes the line gets blurry. Take the diaphragm. It’s technically a skeletal muscle, which usually means it's voluntary. You can hold your breath. You can take a deep, conscious gulp of air before jumping into a pool. But the second you stop thinking about it, your brainstem takes over. If you try to hold your breath forever, you'll eventually pass out, and your involuntary override will kick in to make you breathe again. The body has a "fail-safe" protocol that prevents your conscious mind from doing something too stupid.

Blinking is another one. You can blink on command. You can win a staring contest. But eventually, your nervous system decides your corneas are getting too dry and forces a blink. It's a hybrid system.

Why Does This Matter for Health?

Understanding the voluntary vs involuntary muscles divide isn't just for anatomy tests. It explains a lot of medical conditions. For example, when someone has a "muscle twitch" in their eyelid (benign fasciculation), that’s a voluntary muscle acting like an involuntary one. It's a glitch in the signaling.

💡 You might also like: Getting Help at the University of Indianapolis Health and Wellness Center: What Students Actually Need to Know

On a more serious note, conditions like Gastroparesis happen when the smooth (involuntary) muscles of the stomach stop working correctly. The food just sits there because the "autopilot" signal is broken. Or look at ataxic movements in neurological disorders—the brain wants to move a voluntary muscle, but the coordination is lost, making it look jerky and uncontrolled.

Nuance in Performance and Stress

Athletes spend years trying to turn voluntary actions into something that feels involuntary. We call it muscle memory, though the muscles don't actually "remember" anything—your cerebellum does. When a pro golfer swings, they aren't thinking about the 40 different muscles involved. If they did, they’d mess up. They’ve trained the voluntary system so thoroughly that it bypasses the slow, conscious part of the brain and moves into a faster, more "automatic" loop.

Conversely, stress can mess with your involuntary systems. When you're chronically stressed, your "rest and digest" smooth muscles often tighten up or stop functioning efficiently. This is why people get "butterflies" or digestive issues when they're nervous. Your brain is prioritizing the "fight" over the "digest," and your involuntary muscles are the ones paying the price.

Real-World Examples of Muscle Mechanics

- The Pupil: Your iris is made of smooth muscle. When you walk into a dark room, it widens. You can't force your eyes to stay dilated in bright light just by wishing it.

- The Goosebump: There's a tiny involuntary muscle called the arrector pili attached to every hair follicle. When you're cold or hear a haunting song, these contract. It’s an evolutionary leftover from when we had more fur and needed to look bigger to predators or trap more heat.

- Vascular Tone: Your blood vessels are lined with smooth muscle. They constrict or dilate to manage your blood pressure. This is why certain medications (like beta-blockers or vasodilators) target muscle receptors—they’re trying to talk to the muscles you can't talk to yourself.

Common Misconceptions

People often think "involuntary" means "weak." That is a massive mistake. The heart is arguably the strongest muscle for its size, and the uterus—another involuntary smooth muscle—is capable of generating enough force to push a human being into the world. Involuntary muscles are actually the workhorses. They have higher endurance. Skeletal muscles tire out quickly because they use a lot of ATP (energy) for fast, explosive movements. Smooth muscles are "slow-twitch" masters; they can stay contracted for long periods with very little energy expenditure.

Another myth is that you can "train" involuntary muscles like you do your biceps. You can't do "heart curls." You can improve cardiac efficiency through cardio, sure, but that’s an indirect adaptation. You aren't consciously controlling the contraction; you're just putting the system under stress so the autopilot learns to fly better.

Actionable Insights for Body Awareness

Since you live in this biological machine, you might as well know how to work the controls.

Manage the Autonomic Override

You can influence your involuntary muscles through "vagus nerve" stimulation. Deep, slow belly breathing (diaphragmatic breathing) sends a signal to your brain that you are safe. This flips the switch from the sympathetic to the parasympathetic nervous system, slowing your heart rate and relaxing the smooth muscles in your gut.

Address Chronic Tension

If you find yourself with a tight jaw or hunched shoulders, that’s your voluntary system stuck in a "holding pattern." Your brain is treating these muscles as if they need to be "on" 24/7. Use progressive muscle relaxation—clench a muscle group for five seconds and then release it—to remind your brain what "off" feels like.

Support Smooth Muscle Health

Involuntary muscles rely heavily on electrolytes. Magnesium, calcium, and potassium are vital for the electrical signals that tell these muscles to contract and relax. If you’re constantly cramping or having digestive "hiccups," it might be a chemical imbalance rather than a structural problem.

Respect the Recovery

Because you don't control your heart or your lungs, it’s easy to forget they need recovery too. Quality sleep is the only time your involuntary systems truly shift into "maintenance mode." Depriving yourself of sleep forces your heart to work harder under higher stress hormones, which eventually wears out the "autopilot" hardware.

The divide between voluntary vs involuntary muscles is what allows us to exist as complex beings. We get the freedom to move, dance, and talk, while the silent, automatic systems underneath keep the lights on and the blood moving. It’s a sophisticated partnership. If you want to improve your physical well-being, stop focusing only on the muscles you see in the mirror. Start paying attention to the ones you can’t see, because those are the ones actually keeping you alive.

Check your posture right now. That was a voluntary choice. Now, take a deep breath and let your heart rate settle. That’s you working with the involuntary. Both are essential, but only one of them works even when you're dreaming.