If you walked past the East Harlem Federation Reform School in 1969, you probably heard them before you saw them. It wasn't just singing. It was a literal wall of sound, a tectonic shift of gospel-inflected soul that felt like the sidewalk was humming. These weren't polished professionals groomed by Berry Gordy in a Detroit studio. They were kids. Some were only twelve years old; the oldest were barely out of their teens. This was Voices of East Harlem, and honestly, they should have been as big as the Jackson 5.

They weren't.

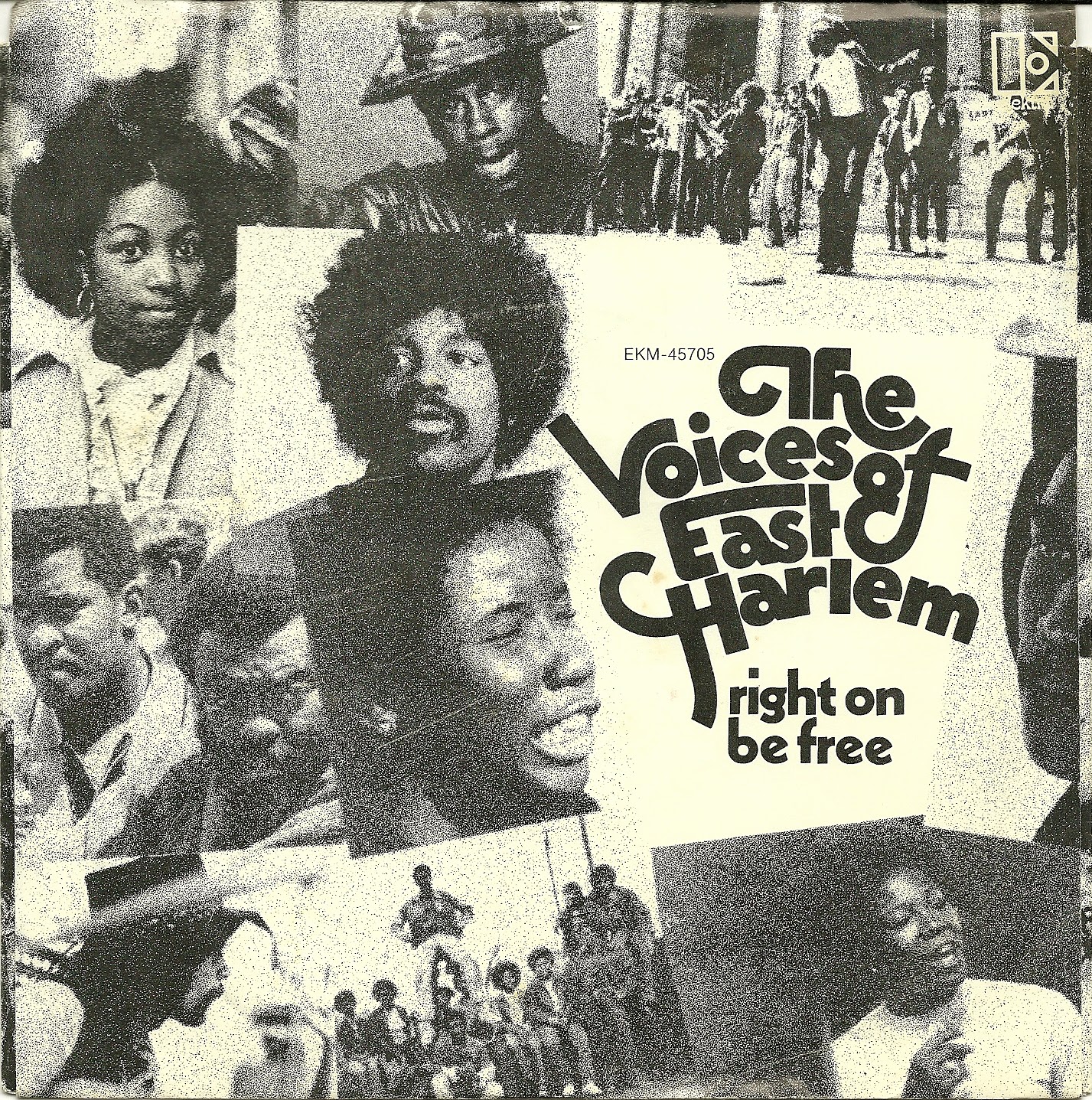

Despite performing at Mount Morris Park for the legendary 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival—the "Black Woodstock" recently immortalized in Questlove’s Summer of Soul—and sharing stages with giants like Jimi Hendrix and Nina Simone, the group remains a footnote for most. That’s a mistake. When you listen to their debut album Right On Be Free, you’re not just hearing music. You’re hearing the raw, unvarnished pulse of a neighborhood trying to sing its way through a decade of systemic neglect and radical hope.

The East Harlem Federation and the Birth of a Sound

The group didn't start in a talent agency. It started in a community center. Chuck Griffin and his wife Anna Leo Griffin founded the ensemble as part of a youth program designed to give kids in El Barrio something to do besides survive the streets. They weren't looking for stars. They were looking for a way to build a collective identity.

The result was an ensemble that grew to nearly twenty members. Think about that for a second. Twenty voices. It wasn't a choir in the traditional "robe and Sunday morning" sense, though the gospel roots were impossible to ignore. It was an urban soul orchestra.

They were loud. They were messy. They were beautiful.

The lineup was a revolving door of local talent, but the energy remained constant. While Motown was busy polishing their acts to appeal to white suburban audiences, Voices of East Harlem stayed gritty. They sang about the "Simple Song of Freedom." They sang about being proud. They sang with a frantic, percussive energy that made it impossible to sit still.

Why the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival Changed Everything

For a long time, the footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival sat in a basement. When it finally came to light, people were floored by Nina Simone and Stevie Wonder. But watch the footage of Voices of East Harlem. You’ll see a group of teenagers dressed in dashikis and street clothes, absolutely commanding a crowd of thousands.

💡 You might also like: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

They outperformed veteran acts.

The lead singer on "Right On Be Free" has a rasp that sounds like she’s lived three lifetimes by age fifteen. The choreography wasn't synchronized like the Temptations; it was organic. It looked like a block party that had accidentally spilled onto a world-class stage. This performance caught the attention of the industry, leading them to a deal with Elektra Records.

The Struggle for a Genre: Soul, Gospel, or Protest?

The industry never really knew what to do with them. Were they a gospel group? Not really; the lyrics were too political. Were they a soul group? Sort of, but there were too many of them to market as a "band." They occupied this weird, liminal space that confused radio programmers.

- Gospel Roots: The call-and-response technique was pure church.

- Political Edge: They were singing "No Free Time" and "Angry" during the height of the Civil Rights movement.

- Funk Influence: By their third album, they were working with Leroy Hutson and getting a smoother, Mayfield-esque sound.

Bernie Houghton, a name often associated with the group’s early management, helped push them toward larger venues like the Apollo Theater and even Madison Square Garden. They played the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970. Imagine these NYC kids flying to a tiny island off the coast of England to scream about freedom in front of 600,000 hippies. It’s wild.

The Leroy Hutson Era and the Shift to "Can You Feel It"

By the early 1970s, the group underwent a massive shift. The raw, shouting energy of their debut matured into something sophisticated. If you're a crate-digger or a hip-hop producer, you probably know their 1973 self-titled album. It was produced by Leroy Hutson, a legend who took over for Curtis Mayfield in The Impressions.

The track "Cashing In" is a masterpiece of mid-tempo soul. It’s smooth, funky, and carries a bittersweet nostalgia. But here’s the thing: as they got "better" technically, some critics argued they lost that frantic East Harlem lightning-in-a-bottle. The group shrank in size. The community-center vibe was replaced by a professional studio sheen.

It’s a common story. To get played on the radio, you have to shave off the edges. But the edges were what made Voices of East Harlem special in the first place.

📖 Related: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

The Missing Link in Music History

We talk about the "New York Sound" and usually point to Lou Reed or the Ramones. Or we talk about the birth of Hip Hop in the Bronx. But the Voices of East Harlem represent a specific era of black and brown excellence in Manhattan that bridge the gap between the 60s civil rights anthems and the disco/funk explosion of the late 70s.

They were essentially the bridge.

Without the vocal arrangements found in "Rare Notes" or "Giving Love," you don't get the same DNA in later New York soul. They influenced how choirs were used in pop music, proving that you could have a massive vocal group that still sounded like the street.

What Actually Happened to Them?

Why aren't they in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Honestly, it comes down to the classic industry trap: bad timing and shifting lineups. By the mid-70s, disco was starting to take over. The massive, politically-charged vocal ensemble felt like a relic of the "hippie" era to some, and too "churchy" for the dance floor to others.

The group eventually disbanded as members grew up, moved on, or tried solo careers. Some, like Monica Burruss (also known as Monica Pege), found success as a session singer and performer. But as a collective, the Voices of East Harlem faded.

The records went out of print. The tapes gathered dust.

It took the digital age and the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul to bring them back into the conversation. When people saw that 1969 footage, the search queries for "who is the girl singing lead for Voices of East Harlem?" spiked. People realized they had missed out on a fundamental piece of American music history.

👉 See also: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The Actionable Legacy: How to Experience Them Today

You can't just buy a "Voices of East Harlem" t-shirt at Target. To appreciate them, you have to dig a little. If you’re a musician, a historian, or just someone who likes soul music that actually feels like something, here is how you engage with their work:

Start with "Right On Be Free" (1970).

Don't listen to it on tiny phone speakers. Put it on a real system. Listen to the way the drums struggle to keep up with the sheer volume of the vocalists. It’s frantic. It’s supposed to be. This is the sound of kids who have a lot to say and not much time to say it.

Watch the "Summer of Soul" Performance.

Seeing them move is as important as hearing them. Their presence on stage—the lack of "professional" artifice—is a masterclass in authentic performance. They aren't performing for a paycheck; they are performing for their lives.

Study the Hutson Productions.

If you're into neo-soul or modern R&B, listen to the 1973 album The Voices of East Harlem. The vocal layering is incredibly complex. You can hear the influence on modern artists like Solange or SAULT. The way they blend individual soloists back into the wall of sound is a lost art.

Research the East Harlem Federation.

If you’re interested in community organizing, look into how the Griffins used music as a tool for social cohesion. It wasn't just a band; it was a social program that happened to produce world-class art. It’s a blueprint for how arts funding can actually transform a neighborhood.

The Voices of East Harlem weren't a manufactured "boy band" or a "girl group." They were a collective. In a world where music is increasingly individualized and autotuned to death, there is something deeply healing about twenty kids from El Barrio shouting in unison, "Right on, be free." They reminded us that the most powerful instrument on earth isn't a guitar or a synthesizer. It's the human voice, multiplied by twenty, fueled by the streets of New York.

Take the time to find their discography. It’s a rare instance where the music actually lives up to the legend. Don't just stream the hits; listen to the deep cuts like "Oxford Town" or "Shaker Life." You’ll hear a version of America—and a version of Harlem—that was loud, proud, and completely unafraid.