They weren't just "gal pals."

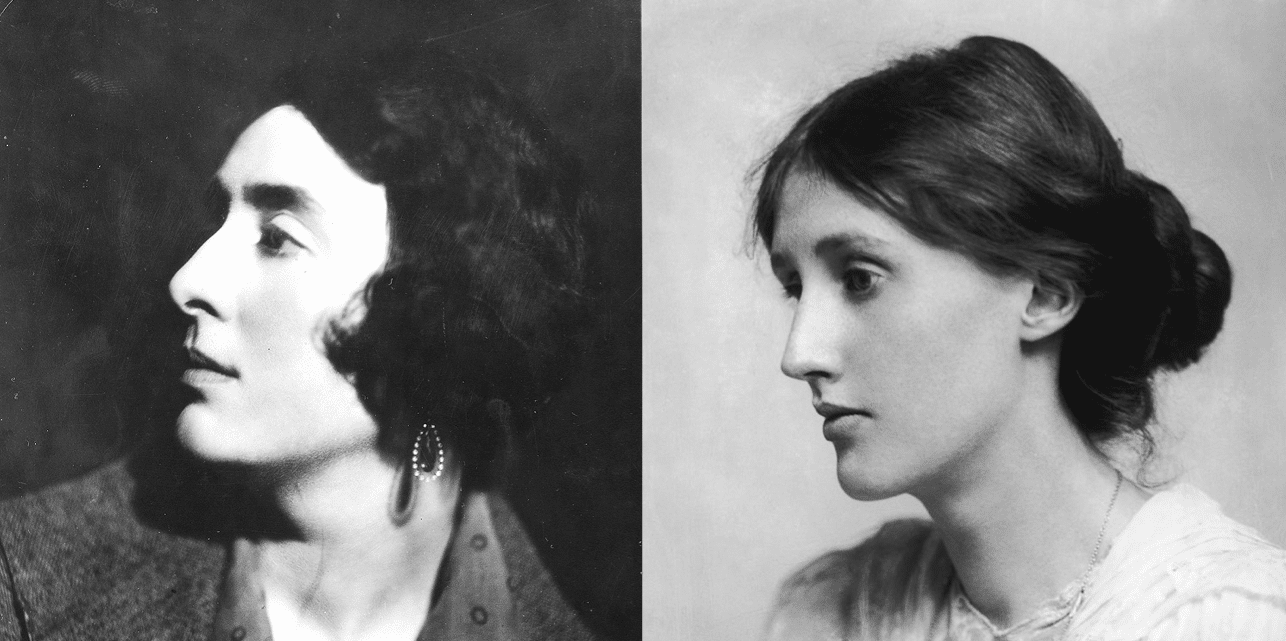

If you’ve spent any time on the literary side of TikTok or scrolled through academic Twitter, you’ve probably seen the memes. They usually involve Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West looking moody in black-and-white photos while someone jokes about "roommates." But the reality of their relationship was a lot more chaotic, messy, and intellectually high-stakes than a simple social media post can capture.

It started in 1922. Post-war London was buzzing, and the Bloomsbury Group was at its peak of "living in squares and loving in triangles." Vita was a flamboyant aristocrat, a successful novelist, and a notorious heartbreaker who wore lace-up boots and lived in a literal castle. Virginia was the cerebral, fragile, and revolutionary genius of modernism.

They were opposites. Honestly, that’s probably why it worked.

How Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West actually met

It wasn't some cinematic "meet-cute" in a library. They met at a dinner party hosted by Clive Bell on December 14, 1922. Virginia wasn't immediately impressed. She wrote in her diary that Vita was "florid, moustached, and parakeet-coloured." Not exactly a glowing review. But Vita was persistent. She had a thing for brilliance, and Virginia had it in spades.

By 1924, they were deep in it.

You have to understand the context of the time. This wasn't just a "fling." It was a collision of two very different worlds. Vita represented the old-world English aristocracy—Sedgefield, Long Barn, and Knole. Virginia represented the new, radical, intellectual vanguard.

👉 See also: Finding the University of Arizona Address: It Is Not as Simple as You Think

The Orlando Connection: A 300-page Love Letter

If you want to know what Virginia really thought about Vita, you don't look at the biographies. You look at Orlando.

Published in 1928, Orlando is arguably the longest and most expensive love letter in history. It tells the story of a poet who lives for centuries, changing from a man to a woman along the way. It’s based entirely on Vita. Nigel Nicolson, Vita’s own son, famously called it "the longest and most charming love letter in literature."

Virginia basically stole Vita's family history—the things Vita loved most—and gave them back to her in a book. It was a way of immortalizing her. Because Vita was a "Sackville," she couldn't inherit her family home, Knole, because she was a woman. Virginia used fiction to give Vita a version of Knole that she could never lose.

Why the "Gay" Label is Complicated

We love to apply modern labels to historical figures. It makes things easy. But for Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, the labels they used were much more fluid.

Vita was openly (mostly) involved with women throughout her marriage to Harold Nicolson. Harold was also having affairs with men. They had what we would now call an "open marriage," but they were genuinely devoted to each other. Virginia’s husband, Leonard Woolf, knew about the affair too. He even encouraged it to some extent because he thought Vita’s presence made Virginia happier and more stable.

It wasn't a secret kept in a dark closet. It was an "open secret" in a very specific, elite social circle.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

The Letters: Passion, Snark, and Real Talk

The correspondence between these two is where the real meat is. They wrote to each other constantly. These weren't just "thinking of you" notes. They were raw.

- Vita to Virginia: "I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia... I love you more than I can say."

- Virginia to Vita: She would tease her, call her a "donkey," and beg her to visit.

Virginia’s writing to Vita is surprisingly playful. We often think of Woolf as this tragic, stone-faced figure who walked into a river, but in her letters to Vita, she is funny. She’s jealous. She’s incredibly human.

Why did it end? Or did it?

People often ask when they "broke up." They didn't really, at least not in the way we think of breakups today. The sexual heat cooled off by the early 1930s, mostly because they were just moving in different directions. Vita was traveling, gardening (she created the world-famous gardens at Sissinghurst), and seeing other women. Virginia was descending deeper into her work and struggling more intensely with her mental health.

But they stayed friends until Virginia’s death in 1941. When Virginia died, Vita was devastated. She wrote that the "terrible thing" about Virginia’s death was that she was the one person who could have described the feeling of such a loss.

The Misconception of "Fragility"

One thing most people get wrong is the power dynamic. There’s a myth that Vita was the "predator" and Virginia was the "victim" because of her mental health struggles.

That’s nonsense.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

Virginia was incredibly sharp and often quite cutting in her assessment of Vita’s writing. She knew exactly what she was doing. If anything, Virginia used Vita as a muse just as much as Vita used Virginia for intellectual validation. It was a partnership of equals, even if the "equality" looked a bit lopsided from the outside.

The Legacy for Modern Readers

Why do we still care about Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West?

It’s because they managed to build a life that defied the rules of their era without blowing their lives up (mostly). They showed that "queer history" isn't just about tragedy. It’s about art. It’s about creating something—like Orlando or the Sissinghurst gardens—out of a connection that the rest of the world might not understand.

They weren't perfect. They were elitist, they could be incredibly mean to their contemporaries, and they lived in a bubble of immense privilege. But their relationship remains a blueprint for a kind of intellectual and emotional intimacy that transcends physical attraction.

Actionable Ways to Explore Their World

If you’re tired of the "Surface Level" stuff and want to actually understand this relationship, don't just read a Wikipedia summary.

- Read the Letters First. Skip the biographies for a second and pick up The Letters of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. It’s much more intimate than any historian's account.

- Visit Sissinghurst if You Can. If you’re ever in Kent, UK, go to Sissinghurst Castle Garden. Vita poured her soul into that place after the affair cooled. You can feel her presence in the "White Garden."

- Watch 'Vita & Virginia' (2018) with a Grain of Salt. It’s a decent movie for the vibes, but it gets a lot of the historical nuances wrong. Use it as a visual aid, not a textbook.

- Tackle 'Orlando' with Context. Don't try to read Orlando as a standard novel. Read it as a biography of a person Virginia loved. Look for the descriptions of the house—that’s Knole. Look for the descriptions of the character’s legs—those are Vita’s.

The story of these two women isn't just a footnote in literary history. It’s the story of how two people used their love to change the way we think about gender, time, and the very act of writing. They didn't just live a romance; they wrote a new world into existence.

Source References:

- The Diary of Virginia Woolf, edited by Anne Olivier Bell.

- Vita and Virginia: The Work and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf by Suzanne Raitt.

- Portrait of a Marriage by Nigel Nicolson.

- The Hogarth Press Archives.

The reality of their bond remains one of the most documented yet elusive relationships of the 20th century, proving that sometimes the best way to understand the past is to read between the lines of the letters people thought would never be published.